70 years ago: Hong Kong's wartime diaries

21 Jan 1945, Barbara Anslow's diary

Submitted by Admin on Sun, 2012-04-22 21:44Book / Document:Date(s) of events described:Sun, 21 Jan 1945Clifton collapsed in cookhouse this afternoon, now in hospital. Probably will be operated on tomorrow for appendicitis.

Played bridge in Mezger's room, with Betty Drown, Dick Cloake and Mez. ((W.J. Mezger; Richard Cloake - journalist)). Nice cake.

Air raid this afternoon - heard no bombs, but planes and a.a. fire.

Last night about 9pm alarm sounded, and a large low plane circled around.

21 Jan 1945, R. E. Jones Wartime diary

Submitted by Admin on Fri, 2015-01-02 12:03Book / Document:Date(s) of events described:Sun, 21 Jan 1945Cloud, E wind, not quite so cold.

Ground rice.

Cotton to Mary & she gave me egg & pork.

A/r 3.40pm. 16 planes heavy stuff dropped. All clear 4.30pm.

21 Jan 1945, Harry Ching's wartime diary

Submitted by Admin on Sat, 2015-05-16 15:28Book / Document:Date(s) of events described:Sun, 21 Jan 1945On roof when drone and saw many planes. Flak then late alert. Formation bombed Wanchai from Oriental Theatre to Naval Yard. Terrible devastation. One third of area. Many casualties. Exhibitionist bombing - 99% civilian damage. Doesn't shorten war by a day. Paper says over 1,000 killed and several thousand wounded. Over 500 buildings demolished.

21 Jan 1945, Eric MacNider's wartime diary

Submitted by Admin on Fri, 2017-01-06 14:49Book / Document:Date(s) of events described:Sun, 21 Jan 1945Sandbach (Memorial service) / Brown

21 Jan 1945, John Charter's wartime journal

Submitted by HK Bill on Mon, 2022-03-21 17:37Book / Document:Date(s) of events described:Sun, 21 Jan 1945Exactly three years ago today we arrived in this camp! Three dead years in our lives! And all this time we have firmly believed we would be free in the next 6 months. Well, it is a mercy that, in the beginning we could not forsee this endless internment. I am sure that if we could have forseen it, many more people would have tried to escape. On the other hand, I think the camp would have been organised on a long term policy instead of our short term, month by month policy and, in consequence, we should have been much better off in the long run. Deaths have been occurring more frequently of late, but in the main the health of the camp has been fairly good when the undernourishment that nearly everyone is suffering from is taken into account.

Now I must write about the war news. On about the 8th of this month, we read in the paper the exciting news that the Americans, after heavily bombarding the coast, landed on Luzon (the northern and biggest island of the Philippines) at Linguan Bay, about 80 or 100 miles from Manila. Most people have felt that the Americans must take the Philippines before landing on the China continent, and this landing on Luzon heralds the conclusion of the Philippine campaign, although there is bound to be stubborn Japanese resistance, for they have called this battle of the Philippines the decisive battle in the Pacific. And then what? Are they coming here?

On Sat 13th at about 9.30 a.m. a fair sized destroyer steamed past Stanley fort and crept out past Beaufort Island and D’Aguila peninsula, there followed a small destroyer, then two big tankers, a small merchantman and then a big one of about 14,000 tons; then followed more small destroyers and a light cruiser, evidently the flotilla leader. It was the biggest Japanese squadron we have seen or are likely to see. It looked as though it was escaping from S. Pacific waters with its supply ships. We expected to hear at any moment the roar of an air attack on the squadron, but nothing happened and they slowly zig-zagged their way out of sight round D’Aguila.

But the roar came alright on Monday 15th. The ‘all clear’ for the morning roll call had not sounded at 8.45 a.m. (it is supposed to go by 8.15) and our wood cutting squad, with a few other workers, were just wandering out and starting work when we saw a flight of about 15 planes coming over. A few minutes later the air raid whistle went, the red flag was hoisted and in we ran. Several waves of planes came over and heavily bombed targets in town and about the harbour. We saw the planes diving on their objectives and saw the puffs of A.A. shells. The ‘all clear’ did not go till nearly 11 o’clock – it was the biggest and longest raid we have had. The air raid interfered with the kitchen staffs’ work and consequently, meals were late. We had to turn out in the afternoon to finish our wood chopping. Then at about 2 o’clock there was a short air raid, but it was very heavy, for at one period there was a continuous rumble of very heavy detonations.

Yvonne had decided, that Monday morning, to prepare a special lunch as we had opened a tin of corned beef. Her antics at the chatty were almost acrobatic, for she would chop a piece of wood, then dash onto the balcony to watch the raid, then rush back and fan the fire and stir the hash, then dash along to the end room of the next flat in order to get a better view. In fact it was all most exciting and lunch was, none the less, a great success.

But what a difference on the next day, Tuesday, 16th 1945. Monday had been fairly sunny but with a good deal of cloud, Tuesday dawned a peerless day. At 8.30 a.m. we heard a distant heavy droning which grew louder and louder, till over us zoomed 15, 30, 40 planes, usually in flights of about 15. People were streaking for their blocks before the whistle went, for there was no mistaking that hum. They were nearly all medium sized bombers. Then the bombing and the A.A. firing began. Planes went roaring down, one after the other, in almost perpendicular dives with the crash of bombs and roar of fresh waves of planes coming in from the East.

I saw the leading plane begin to turn to the north, in the direction of the town, then looked away at the more distant planes. Suddenly, Yvonne said, “It’s on fire”.

Looking up, almost directly overhead, we saw the leading plane and the one on its right side fall apart from each other. The leader was just emitting a cloud of smoke and slowly going into a spiral dive and then the second plane after trying to straighten out, like a wounded bird, also went into a lazy spin and came slowly down, turning about like a falling leaf, utterly helpless and giving out a cloud of black smoke.

The first plane was soon enveloped, in mid air, in sheets of flame and clouds of smoke, but suddenly there was a puff of white and to our joy we saw a parachute open and detach itself from the wreck. It looked surprisingly large when it had opened and at the end, swinging violently against the azure sky, was a tiny black speck. A bulge of white appeared also from the second plane, but the parachute never got clear and was dragged down with the burning plane. It was absolutely horrible to watch, and yet we had to, as if fascinated.

In all the raids over HK this was the first actual disaster we had witnessed. At no time had there been a puff of Ack Ack smoke anywhere near the planes and we are convinced that somehow they had crashed into each other. None of us in our room actually witnessed the crash, as our attention had been diverted by some terrific diving that had just started over the town, but, as I have said, I saw the leading plane turn right, across the bows of the starboard machine (they were flying in very close formation) and when I next looked these two planes were falling apart.

Freddy Morley told me that he watched the whole accident and that the planes had crashed into each other, he said it looked as if the second plane slipped slightly sideways into the first one and then they just peeled apart and turned over. They seemed to come down so slowly, and when both were halfway down we saw a huge splash in Tytam Bay, not far from Stanley beach. A column of water went up and then for a long time the water came seething and foaming up in a big circle: there was no explosion and I think it must have been one of the heavy red-hot engines that had fallen out of the first plane. We also saw shining scraps come turning and fluttering down – most probably pieces of the body casing. Eventually the two planes crashed, not far apart, just out of our site behind the Stanley range of hills and clouds of smoke came up from the brow of the hills. By this time the parachutist had descended quite along way and we could clearly see the small human figure, suspended from his huge white mushroom. There was practically no wind and the airman went down behind the hills not very far from the planes. The collision must have occurred over the camp but the momentum of the planes carried them on.

Discussing later, we decided that the pilot of the second plane either made a mistake or turned in the wrong direction when the order was given or he did not turn quickly enough or, quite probably, there happened to be an air pocket between the planes into which both of them slipped. The air during such a raid must be full of air pockets. Some people say that perhaps a smokeless A.A. shell exploded between them, but this does not seem very likely – I don’t know how smokeless is such a shell, but there certainly was no trace of smoke between the planes. It was a very sad sight and cast a gloom over all of us.

The Japanese have frequently stated that they will execute all American airmen who are taken prisoner by them for their alleged indiscriminate bombing of Japanese civilians. So we were apprehensive about the safety of the parachutist and felt his companions must certainly have perished. It was rather magnificent the way the rest of the flight went steadily on, as if nothing had happened, and proceeded to attack their objectives. Over 100 planes must have come over that morning and, when they had finished their attack they reformed and the flights disappeared in a southerly direction – which they have never done before – and they made us wonder if they were planes from aircraft carriers of the American fleet. Their size also seemed to strengthen this suggestion. (Later this turned out to be the case and, of course, caused a good deal of excitement). Gradually they disappeared and the ‘all clear’ was sounded at about 12.30.

The Corra’s were coming to us for tea and bridge that afternoon and when the ‘all clear’ sounded I went down to our garden to pick some carrots with which to decorate the scone (or ground rice slab!). While there, I thought I would do a little watering and had just taken out the can when I heard distant thundering and presently I again saw people running for cover. I hadn’t time to put away the watering can and get back to my block, so I decided to wait down in the garden, where I was out of view of everybody, expecting it to be a short sharp raid as it was on the previous day. After a bit, things quietened down and, having waited half an hour, I decided I would pretend I did not know a raid was on and just walk back. The Japanese sentry on the point either did not notice me or thought the raid was over, for he neither shouted nor fired and I arrived home without adventure. I was lucky I did break the rules and go back, for the raid lasted till about 6 p.m. and the old MQ gardens became a hot corner during the afternoon.

Well, the Corra’s came and we had our tea and had just dealt out the first hand when the raid became intensified and we all dashed along to the end room to see. Then planes came over and bombed something on D’Aguila peninsula and our windows rattled. I was watching from our verandah when I heard a roar overhead, and saw a black shadow race across the football field, heard the rattle and roar of the aeroplane’s machine gun and cannon and saw two small shells burst on the concrete path just inside the prison. All about the camp the Formosan guards were letting off with their rifles at the plane and people in Block 5 saw machine guns in the prison opening fire.

We were dashing about the corridors of this block when there was a tremendous crash and rush of air of the blast, which rattled the windows and blew papers over the floor. The whole building shook. For a moment we wondered what had been hit and then Kathleen Rosselet in the end room which overlooks the prison said, “Look, Look! There it is”.

And there she was, standing in front of an open window, with Miss Nailor’s cigarette papers, that the blast had blown from the cill, all about her feet, pointing to a thick cloud of smoke just outside the prison wall and just beyond the barbed wire fence of the MQ gardens. I should have had my beard singed if I had remained down there! Kathleen didn’t seem at all perturbed. Shrapnel was falling about the camp. Earlier in the day we had seen Tytam Bay peppered with falling shrapnel. Then the commotion in the camp subsided. Most of us had left our rooms and stood or sat in the corridors between brick walls. After this shake up we opened our windows to minimize the danger of the glass shattering. Then we went across to the Corra’s room in block 5 and sat in the grateful sunshine on their balcony. There was a good deal of dashing about by the Japanese in the prison.

Then Po Toi Island was attacked by two planes and a little later we saw four planes fly over Waglan (the island which commands the southern approach to HK harbour) and carry out diving, dropping their bombs, rising, wheeling and diving in again in a perfect figure of eight attack from two directions. Waglan was attacked several times in this manner during the day. There is a lighthouse on Waglan and probably observation posts. We don’t know what is on Po Toi; our big wireless station is on D’Aguilar. By this time big clouds of smoke were rising from the direction of Victoria and D’Aguilar, Waglan and other points (including the spot beyond our gardens where the grass was on fire) contributed their quota of smoke until there was a thin haze right over the sea. From about 4 to 5 o’clock things seemed to quieten down a bit and we heard more distant rumblings. Y and I went back to collect our hot water and see when food was to be served.

Then, suddenly things started to happen again. Everyone got into the hallway or the main staircase hall and people from the top flat came down to our floor or ground floor. There was a roar of a plane passing over; a terrific crash which shook the whole building (due to another bomb which hit the rocks at the south east corner of the prison not far from the first one); then the roar of other planes and the shattering chatter of machine guns and small canon together with the tinkle of glass. We felt the tremendous swish of the plane as it roared right over our building and dived at the machine gunners in the prison.

Then there was another explosion, which shook the building again, and looking out of the hall window I saw a huge column of smoke rising from the direction of the hill. Some one said, “They’ve hit headquarters”. And I felt myself feeling very sorry for the Japanese there.

It was a most unpleasant experience and there were a good many white and scared looking faces about and many crying children. And then, at about 6 o’clock, everything quietened down, and people drifted back to their rooms.

We found the pits of three machine gun bullets in the parapet wall of the balcony, two more on the walls at the side and a sixth bullet (little Willie) had dug a small pit in the concrete floor of our balcony, ricocheted upwards, gone through the window by our bed, through the net curtains and was reposing amongst splinters of glass on our bed. This bullet, like all the others was a heavy armour piercing bullet with a very hard steel core and a brass or copper covering.Harold Blake was grinding rice in the hall, near the front door of our block. Mrs Fox (I think) who was standing beside him said, “Here, I don’t think this is safe” and moved off to her flat on the ground floor.

Blake followed and was just walking through the front door of the flat when a bullet came through the first floor staircase window, down the first flight of stairs and went clean through his foot near the ankle and (most curiously) the bullet case (about 4” long) had lodged itself in the fleshy part of his thigh. Poor chap, he lost a lot of blood and at one time the doctor in charge thought he might have to amputate his foot, but he is recovering now.

I went around to the Armstrong’s room to see what had happened up the hill. I found Jack looking out of the window and, doing likewise I saw Hara talking to Gimson. He had come to give Gimson the bad news that Bungalow ‘C’ (Maudies old home) had been hit by a bomb and that one person was killed and about 5 injured. So it was Bungalow ‘C’ and not headquarters that had been hit. I wish Hara’s first news of the tragedy had been correct.

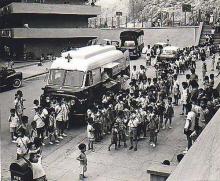

St Stephen’s organised stretcher parties and we saw some of the casualties going to hospital. Watanabe, the new Japanese interpreter, had run down to the hospital immediately (before the ‘all clear’ had gone) to warn the hospital and dispatch First Aid parties. A stretcher passed our block on its way back and I said to Butler, “Many casualties?” and he replied, “About 8 or 9 I think”.

“Killed?” I asked. “I’m afraid so, but they haven’t extricated them yet”.This was much worse than we had thought at first.

The next day the official list was posted on the board and the number killed was fourteen! It was awful. Most of them were well known friends of ours. The list is as follows:- Ernest Balfour, F. Bishop, Peggy Davies, James Denis, Oscar Eager, “Penny” Guerin, Adam Hollands, Mrs Johnson, Alec and Betty Hyde-Lay, Edward and Mable Searle, Gordon Stopani-Thompson, and Mr Willoughby.

Hollands and Willoughby and Miss Davies were the only people we did not know well. There were one or two narrow shaves too. Freddie Dalziel was in hospital which saved her life, for the servants room in which she lived was completely wiped out; Baily, who was in the same room with Gordon ‘Stops’ which received the direct blast, escaped with his life because he was sitting on his bed in the corner of the room and some brickwork obstructed the blast. Hundreds of little blood vessels in his face were ruptured. Stevens and Miss Wisket had head injuries, but not serious. Young Stuttsbury was in the camp bakery, which was lucky for him, though his room was not badly damaged. The Langston’s were lucky; their room collapsed all about them and Langstone was blown out of the door. I think 13 or 14 escaped, either because they were away from the Bungalow or because brickwork saved them.

There were several lucky visitors who had visited the bungalow during the mid-day raid ‘all clear’ but who had sneaked back to their own blocks, as I did from the garden. One woman had spent the afternoon there with her baby but at about 5 o’clock she decided to go back to Block 10. Her husband who was watching from their block, saw her coming and waved her back, but it was past the baby’s meal time and she ran on and got safely home.

We could not sleep that night for thinking of our friends, taken so suddenly and unexpectedly from our midst.

If this camp is again hit by bombs it will not come as such a shock and surprise to us. We have always considered ourselves safe in this place, even if uncomfortable. Now, however, we shall not expect immunity from war risks if the Japanese station legitimate objectives within the vicinity of the camp. They had brought a mobile gun and stationed it on a small clearing beside the road at the foot of the bank on which Bungalow ‘C’ stands. Also, the small tanker which went ashore on Po Toi and which the Japanese towed to Stanley Bay, is still stern down in the Bay. This ship opened fire on the planes with it’s gun in the bows and a plane dropped bombs near to it and the two salvage ships, which have, for some time, been attempting to raise it. The gun was much closer to the bungalow than the ships and the difference in elevation between the gun and the bungalow probably foreshortened the approach to the gun and was responsible for the accident. No one knows exactly. The bomb landed in the small courtyard between the bungalow and the garage. It completely removed the four brick walls of the garage and the flat concrete roof came straight down (hardly damaged) on top of the four who were in the garage playing bridge. They were undoubtably killed by the blast and knew nothing of the collapsing roof.

Salter showed me over the bungalow a few days after the tragedy. The bungalow had a pitched roof but it was made of concrete. This accounts for the somewhat surprising way in which one corner of the roof was left projecting in mid air when the walls of the girls’ room were blown clean out. All around the building, under the eaves, was a horizontal crack which showed how the whole roof had been lifted an inch or so by the blast. On the blackened underside of the roof (near the apex over the front room) were the imprints of two feet, one with a shoe and one a bare foot, also the imprint of a bent arm. Many of the poor victims were badly dismembered and bodies, furniture and fittings were blown right down the hill.Bishop, Mackenzie, Salter and Taylor were all officers of my R and D Depot during the war. They kept together as a mess from the day of the capitulation and were all living in the same room in the bungalow; no doubt I should have been with them if Yvonne had not been in Hong Kong. ‘Bish’ was in the kitchen when the explosion took place or he probably would have escaped with the others. He was the best of all my officers and a grand fellow. Paterson (officer in charge of all R and D work) mentioned his name especially in his official report. I know this because he first discussed it with me.

Poor old ‘Stops’ had been with us in Jack’s flat and the ‘Lai Koon’ Hotel when he and Jack Robinson, the two Bidwell’s and Y and I formed a mess of six. Had Gordon and Jack not stayed behind in the hotel with four others, for a day or two to see that everyone’s luggage was forwarded, he might still have been living with us. But we could not reserve any places for absent friends in the pandemonium that accompanied our settling in here. He has a wife and four children waiting for him in Australia and Bishop has a wife and two children. The Hyde-Lay’s have two children in England: Mrs Macklaughland, the old granny, escaped without injury – an irony of fate for, I suppose she hasn’t many years of life left anyhow. Mrs Johnson has just lost her husband, Monte. He developed TB in camp and died a few months ago, so one does not feel that Mrs Johnson’s death is quite such a tragedy as the others.

The funeral was held on Thursday, all 14 sharing a communal grave. Only close relatives were allowed to attend and for those of the victims who had no relatives in camp, one person was allowed to attend as the relative’s representative. Both Protestant and Roman Catholic clergy took part in the service.

Clifford Large, who attended the funeral said that old Father Meyer was concluding his part of the service when two Formosan guards came marching up from the Prep School, approached on either side of the grave, presented arms over the grave and then marched away again. Large also said that on the Tuesday, immediately after the accident when he and Father Hesler were making their way to the bungalow, they met Hara who said, “I am very sorry this has happened,” to which Large replied, “It is just the fortunes of war,” and Hara answered, “Yes, but war, what is the use?”

I must say that the Japanese have always shown their concern at the killing of civilians in wartime. Gordon ‘Stops’ himself told me (he was captured with a number of other civilians before the capitulation of Hong Kong) that he was asked to name several buildings on the Peak which were near our gun positions which the Japs intended to shell. When he said that one of them was the War Memorial Hospital, the Artillery Officer in question was extremely angry (and quite rightly in my opinion) and said that if by accident he hit the hospital he would be accused of firing at the hospital. It is probably this regard for civilian lives that makes the Japanese so mad over the ‘carpet bombing’ over Japan and has made them threaten to execute all enemy pilots taken prisoner, who are culpable. At the same time, the Japanese treatment of captured civilians has often been terrible, and many outrages were perpetrated in HK alone.

Five of the survivors of the bungalow disaster are still living there, in spite of the fact that most of their doors and windows have been blown out. They are trying to get a move, as the building is just not safe for further human habitation, but everything is so crowded that it is difficult to fit them in.

One despicable thing that happened after the bombing was the looting that took place about the bungalow. On the very evening of the bombing a few miserable specimens were caught removing vegetables from the bungalow gardens and personal belongings that were strewn about. It was soon stopped, as may be imagined, but I’m afraid it shows the level to which some of the internees have sunk. I suppose perpetual want is apt to harden people and upset their normal sense of balance and self-respect.