An Incident in Hong Kong Baking in 1948 or How Things Happen

Primary tabs

Earlier this year I came to Hong Kong on a research visit. My main interest was in the tumultuous events of the Second World War, but one of the first files I inspected in the Public Records Office was a set of documents related to the more mundane matter of an application to the Hong Kong Government from one of the Colony's leading companies, Lane Crawford, who wanted special treatment in the matter of some land they hoped to acquire for the erection of a new bakery. The application was made in the middle of 1948, and as it wound its way slowly through the bureaucracy – it took more than a year before the matter was settled – various civil servants debated its merits in comments now to be found in HKRS156-1-1460, 'Application From Messrs. Lane, Crawford Ltd. to purchase an area at King's Road for the erection of a bakery'.*

These apparently dry documents about a minor matter – the application came to nothing anyway – give a fascinating insight into the way history actually happens.

The civil servants no doubt had their minds focused on the basic issue before them as they minuted: is it fair to give what one of them called a 'private, for profit, company' more favourable treatment than their competitors? And when their minds wondered it was almost certainly to the usual things – troubles at home, the weekend prospects of a favourite sporting team, the imminence of lunch....But their pens were nevertheless sometimes moving in response to actors other than those whose names were before them - their colleagues and senior Lane, Crawford staff - and to events taking place a long way from their offices in Victoria ((now Central)). On some occasions they became aware of this, and made particular references to support their case, on others the thought that was influencing them just flickered through their mind or was lodged there so deeply it didn't need to be dragged into the light of day.

The file shows the way in which 'levels' of history interact: memories of the war, the development of baking in Hong Kong, changes in relations between the races after the Japanese occupation, and the great events of world history in the late 1940s were all involved in creating the mind-set these civil servants brought to the consideration of a relatively minor piece of office business, a commercial manoeuvre that most Hong Kong residents never learnt about and which came to nothing in the end. And the forces that moulded events in post-war Hong Kong also moulded my family history, as I was reminded at the moment when my father made a significantly anonymous appearance in the pages before me!

But to understand these events of 1948-1949 we need to place them in the context of what had happened in the Hong Kong baking business up to that point.

Perhaps unusually, baking played a role in history in the early days of the British colonisation. Lane Crawford, now a company of many interests, dominated the expatriate baking scene in the years leading up to the Japanese attack of December 1941. It owed this position to an attempt to poison the British community through its bread that had been made in 1857 as a 'guerilla' action in support of China during the Second Opium War (1856-1860). Although Zhong Alum, the baker thought responsible, was acquitted by a Hong Kong court, it was clear that the European community would not trust Chinese bakers in the foreseeable future, and this enabled Thomas Lane and Ninian Crawford, who in 1850 had opened a matshed-based business orientated to selling 'hard tack' to the Royal Navy, to build a proper bakery and grab much of the market (1).

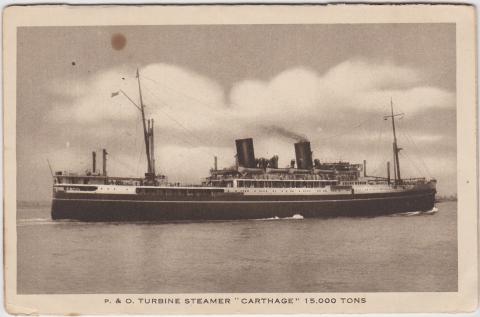

By 1926 Lane Crawford had diversified and were in a position to erect a fine building in Victoria– it's a mark of the company's success that their previous 6-storey property had been outgrown after a mere 21 years (2). Exchange House in Des Voeux Road Central acted as Hong Kong's most prestigious department store and the Company Headquarters, as well as housing the Colony's Telephone Exchange and still affording space to rent out as offices to other organisations. The Café Wiseman was the popular on-site restaurant, with its own bakery – in 1940 it became one of the first buildings in Hong Kong to adopt air-conditioning. Baking bread for sale to the general public was carried out in Burrows Road in Wanchai and by 1938 this facility had become too small; at the ordinary yearly meeting in May of that year Company Chairman J. H. Taggart announced that 'eminently suitable' new premises had been acquired in the Happy Valley part of Stubbs Road for a modern bakery. (3) They'd hired a new bakery manager, perhaps to oversee the move - little did they know that he'd altered his birth certificate to appear older and more experienced. The enterprising forger, my father Thomas Edgar, had arrived in Hong Kong earlier in the month, having embarked on H.M.S. Carthage, bound for Yokohama, on April 8. (4)

He was was the son of a soldier and didn't wait long before offering his services to the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Force – at that time still genuinely 'volunteers'. But in one of his few surviving pre-war letters (probably written in October 1938) he tells his family that he'd just been instructed not to join the fighting units but to get the bakery ready for any 'emergency' – in other words, like it or not, he was in the Essential Services division and would not be expected to bear arms in the event of an attack. (5) During the next three years he made a number of preparations for war, (6) while continuing to enjoy all that Hong Kong had to offer the 'white' elite.

On December 8, 1941, the old world came to an end with the Japanese attack; my father was appointed, presumably as pre-arranged, Deputy Supply Officer – Bakeries. Until December 21 he and his mainly Chinese staff kept up production at Stubbs Road. On December 21, unable to use the electric ovens because of the fall of North Point Power Station, and with the Japanese army close by, he moved to two small Chinese bakeries in Wanchai, the more important of which was the Ching Loong in Queen's Road East. There followed a desperate attempt to meet the needs of both the civilian and military populations of Hong Kong Island. (7)

After the Christmas Day surrender he spent the first 15 months or so uninterned to bake for the hospitals, and during this period he and his fellow bakers resumed production at to the Ching Loong; at one point, the Japanese, who had taken over the Stubbs Road facility, offered him his old job back; this must have been highly embarrassing, as baking for half-starved hospital patients was one thing while working directly for a Japanese commercial enterprise was another, and might have led to collaboration charges after the war, but somehow he managed to side-step the offer. During the 15 months or so he worked at the Ching Loong he became friendly with the owner-manger, Ng Yiu-cheng, and his family. On May 7, 1943, in the wake of the arrest of Dr. Selwyn-Clarke, he and the other residents of the French Hospital were sent to join the majority of the British civilians in Stanley Internment Camp. (8) On liberation in August 1945 he wanted to get back to his family in Windsor as soon as possible but was forced to spend until summer 1946 getting the badly-damaged Stubbs Road bakery back in working order. (9) On August 15, 1946 Evelina, the wife he'd met while baking at the Ching Loong and married with Japanese permission in June 1942, had lunch with her friend Barbara Anslow and told her that they were leaving on Sunday 18th. (10) They flew back to the UK by plane (a ten day journey at the time), so it looks like he managed to get one (maybe even two) air tickets as compensation for his extended detention in Hong Kong – I don't recall coming across post-war leave that was taken any later. Evelina, with her Eurasian good looks, sophisticated hair-style and habit of smoking Lucky Strike (only Lucky Strike) cigarettes out of an elegant holder made quite an impression on the working class Edgar family – but that's another story. Passport stamps show they embarked from Southampton on March 4, 1947 and landed in Hong Kong on April 1 and soon thereafter my father resumed his work as manager of the Stubbs Road bakery.

His company had recovered well from the occupation. War-time losses and rehabilitation costs were estimated at over HK$887,000 and this might have been the reason for the sale of the Exchange Building in the ten month period ending April 30 1946, but profits (including from the sale) were almost HK$650,000. (11) Things soon got better still. Former Stanley internee F. C. Barry told the twenty first annual meeting that in the second 'highly satisfactory' post-war trading period - the ten months ending on February 28, 1947 - profits were over one million HK dollars. (12). Barry was hopeful that the claim against 'the Military Authority' would be settled soon, but he admitted that the main 'cause for concern' was the bakery. It was impossible at that time to procure the machinery needed to make good the damage cause during the occupation.

At Lane Crawford's twenty second yearly meeting held on August 26, 1948 it was announced that an acceptable compromise had been reached with the Military Authority and that most of the 'old outstanding account' had been settled and much of the rest was expected to be settled 'in the near future.' But this ordinary meeting was followed by an Extraordinary General one: Barry explained that the company needed to raise new capital, mainly to build a bakery, as the Stubbs Road lease had run out on June 30 and since then they'd been occupying the premises on a monthly rental basis. The bakery was still a going concern as the company wanted to avoid 'the loss of revenue' that would follow its closure. (13). Although there is no mention of this in the newspaper report, there was a precise plan for use of this capital in place.

Lane Crawford manager A. W. Brown was spearheading a company attempt to get a plot of land 'by private treaty' rather than at the full competitive price of a public auction. They changed their mind on at least one occasion, but it seems the main emphasis was on a plot off King's Road (adjoining I C 6378). But why did they think the government would give them special terms on a commonplace commercial transaction?The bakery's landlord wanted them out after the expiration of the ten-year lease on June 30, and, although they had protection under the law and could have continued the to occupy the site on the monthly basis described to the Extraordinary General Meeting, they were unwilling to invest in the new machinery they needed without the security of tenure given by their own land. The reason they wanted the Government to step in and help them get it at a favourable rate was simple: the price at public auction would have been so high they believed the bakery would run at a loss. Almost all land in Hong Kong is technically owned by the Government and 'sold' to individuals or groups on a leasehold basis only. Lane Crawford were after a 150 year lease without an intermediary landlord of the kind they dealt with over Stubbs Road, and the company were hoping that in their case one of the basic ideas of laissez-faire capitalism would be ignored: that Government shall not discriminate either in favour or to the prejudice of any individual or private company. Why did they hope that 'market forces', which set the land prices for everyone else, would be quietly set aside?

An unidentified civil servant who supported their application makes the nature of their case clear: he points out that in the various crises he'd known since coming to Hong Kong, the Colony had always 'fallen back' on Lane Crawford. There was, therefore, in his opinion, a case for seeing the company 'firmly established in a suitable area ready to supply our essential services with daily bread' in case another emergency arose again soon. The nature of this possible 'emergency' was obvious: on July 20, 1946 the uneasy anti-Japanese truce between the Communists and Nationalists on the mainland came to an end with a full-scale Nationalist attack. In the second half of 1947 the Communists began to get the upper hand, and by the spring or summer of 1948, when Lane Crawford began their own campaign, it was clear that they were likely to win and that subsequent action against Hong Kong was possible.

In a letter of June 13, 1948,** Brown explained why the company were seeking land for a bakery to supersede Stubbs Road. New machinery was urgently needed:

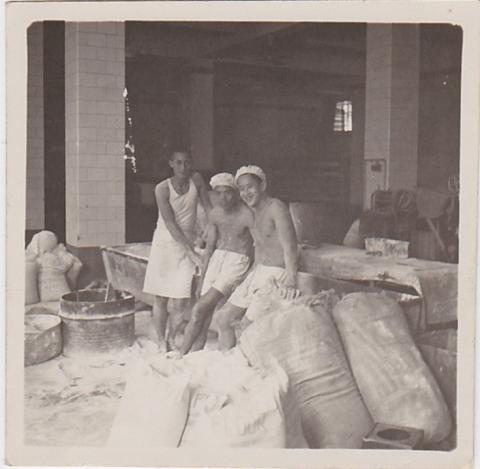

Our present ovens and equipment were gravely misused during the Jap occupation of the Colony, and are operating at only fifty per cent efficiency despite constant care and repairs. Certain phases of production which, pre-war, were dealt with by machines, are now having to be carried out by hand.

Brown acknowledged that the expiration of the lease and the landlord's desire to take over the plot wasn't really the problem - they were protected from forcible eviction by the Land Ordinance. Their real fear was the 'breakdown of our plant'. The machinery had already outlived the span estimated by surveyors during the re-occupation and the company was unwilling to install new machinery without the security given by having their own land.

In a letter to the Director of Public Works – Victor Kenniff, an Australian who came to Hong Kong in 1946 (14) - dated July 21, 1948, Brown laid out the historical case that convinced some civil servants: Lane Crawford had kept the bread coming during the strike of 1922 and in the crisis of 1925-1926 when Hong Kong had been almost brought to its knees by an economic boycott and general strike instigated by a nationalist administration in Canton. He mentioned also the more recent and still potent experience of the Japanese attack and the role played by the Stubbs Road bakery as the main producer of bread for civilians and eventually for the armed forces too.

The company was important enough for this application to merit a personal note to Brown from Colonial Secretary David MacDougall – perhaps the manager's own prestige helped, as he was one of the small number of people honoured after the war for their services to fellow Stanley internees. (15) Seizing the opportunity to make his case direct to the Colonial Secretary, Brown replied on December 22, 1948, again emphasising the historical record:

During the siege of the Colony in December 1941 our Bakery undertook the supply of bread for all essential services and the community, as practically all Chinese and other bakeries closed down. Following the loss of the Army Bakery at Deepwater Bay ((December 19)) we carried out the additional task of maintaining bread supplies for the Forces. Also, the speedy resumption of bread supplies to the community on the re-occupation of the Colony in 1945 was, as you know, due to our placing our organisation and staff at the disposal of the British Military Administration. We would mention that we made no claim on Government for use of our premises and machinery under requisition during the War, and whilst our claim for replacement of lost machinery etc., is still outstanding, the prospect of obtaining any compensation therefor ((sic)) is most remote.

He must have been aware that the Colonial Secretary, who had participated in the defence himself before leaving Hong Kong as part of the daring escape centred around Admiral Chan Chak, would be reading his words on the eve of the seventh anniversary of the surrender.

Nevertheless, it was obvious things had changed in Hong Kong since the war and Brown's company didn't have the dominance of the 'European' baking market it had enjoyed in 1941. One sign of the new order was that by the time of Brown's Christmas 1948 letter my father was no longer with his company. A civil servant who was opposed to special treatment for Lane Crawford pointed out in a memo of January 24, 1949, that the Chinese-owned Garden Bakery now supplied 'the bulk of the higher class European cafés' and held 'contracts for supplying all H.M. shops and shore Establishments in Hong Kong'. And, he continued, 'I understand (they have) a European manager'. This was almost certainly my father, although the only document in his archive relating to the Garden Bakery is an invoice dated October 24, 1949. His new employers were said by the same writer to be 'in keen competition with Lane Crawford' - and they too were seeking more land, in their case to install an oven over one hundred feet long. He ended by producing his trump card: in any emergency the Government would undoubtedly take over both bakeries. He concluded his argument with the statement that he was unable to 'support Lane Crawford getting land for 150 years by private treaty'. Victor Kenniff also opposed the application, so the civil service was thoroughly divided.

Who were these upstart challengers? Garden Bakery was founded in 1926 by cousins Cheung Tse Fong and Wong Wah O. The Company flourished in spite of a serious fire in 1932 and distinguished itself by support for China after Japan's 1937 attack: at one point it manufactured 200,000 pounds of army crackers in seven consecutive days, 'a feat considered impossible until it was achieved' as the Company website tells us with justified pride. (16) One source claims that in 1938 they installed the first industrialised baking facilities in Hong Kong– if so they must have just beaten Lane Crawford to the punch.(17) This was a 1400 square meter bakery in Castle Peak Road – because this was in Kowloon and would therefore fall into Japanese hands relatively early it would have been ruled out by my father as he considered his pre-war 'Plan B' - what would he do if the Japanese attacked and he couldn't use his own bakery?

Like Stubbs Road, Garden Bakery was commandeered by the Japanese during the occupation, but judging by the progress made by 1948 and the contrasting (although possibly exaggerated) lamentations about the difficulties faced by Lane Crawford, it seems to have got up and running more quickly. Perhaps Garden were paradoxically helped by the fact that their equipment was completely destroyed, while in Stubbs Road it survived, albeit in poor shape, the bakery's multiple war-time transformations: it had been used to salt fish, make rattan baskets and produce buttons for military uniforms. (18)

Garden had been set up in 1926 because its founders had noted a growing Chinese demand for 'Western' bread and cakes but the fact that their first retail branch was opened in Des Voeux Road Central the following year might suggest that they already had in mind the possibility of developing a significant 'European' market. If so I've not been able to find evidence of any success in this.

But after the war things were different. In 1947 Garden registered as a limited company and it was now ready to take on its mighty rival. I know nothing about the circumstances behind my father's switch of allegiance, but he never said anything negative about Lane Crawford, so my guess is that he was attracted by a higher salary and perhaps a new challenge.

After the war, the Chinese population, which had suffered so much under the Japanese, came into its own. Hong Kong, reduced to an almost literal Dark Age by the occupation – practically the only electrical supply in August 1945 was to the Japanese headquarters in the Peninsula Hotel – desperately needed economic recosntruction. Although it had by no means disappeared, the extensive racism of the pre-war order had significantly diminished. It was a time for Chinese enterprise and entrepreneurship to flourish all over the economy, even in areas of traditional expatriate dominance.

The growing Chinese post-war input into bakery can be seen from the development of the Ching Loong, so important to my father and the other European bakers during the hostilities and the first 15 months of the occupation. In the spring and early summer of 1947 it too became a limited company, albeit a small and family-based one. (19) It seems that the company operated successfully for the next 15 or so years before it applied to voluntarily cease trading in 1963. All debts were to be paid, so this was not a bankruptcy but probably the retirement of the owner-manager Ng Yiu-cheng with no family members wishing to succeed him. Ng had been honoured with a Certificate of Merit for his role in the escape of my father's friend and fellow wartime baker, Staff-Sergeant Patrick Sheridan. (20) One official source stated that Ng was already 'fairly well-off' in the immediate post-war period, so there was no need to give him the kind of financial reward paid to other Chinese men and women who had helped the British during the occupation. By 1951 he had become a British citizen and his family had joined him in this status by the time of the liquidation.

So, although Lane, Crawford remained the dominant force in the Colony's baking in 1948/1949, the trade, like much of the rest of Hong Kong's economic activity, was seeing an ever-growing Chinese presence. Nevertheless, the company chairman A. Sommerfelt told the ordinary yearly meeting on August 26, 1949 that in spite of the 'intensive' competition from Chinese bakeries they'd still sold much more bread than last year (21) They were still the biggest baking concern, after all, and there was still the historical argument, and perhaps a sense that, in the event of an attack from China, only a British company could be considered 100% reliable.

No decision was made in 1948, and the affair dragged on into the spring of the next year with Government opinion completely divided. It seems that in April the Company switched their application to another plot of land: bureaucracies being what they are, this was unlikely to have helped bring about a speedy resolution. But on May 5, 1949, a civil srvant with the initials D. C. S., minuted to the effect that in the current 'semi-emergency conditions' the matter should be referred to the Governor in Council.

Now, appeals to history and to past service are all very well, but I don't think its overly cynical to point out they don't always work, especially when money is put in the opposite scale. D. C. S.'s minute makes it clear that what gave the company's application its power was not its service in 1922, 1925 or 1941 but Hong Kong's situation in the spring of 1949, which was even more precarious than when the process was begun a year or so before. On April 23, 1949 the Communist forces captured the Nationalist capital of Nanjing and the civil war was effectively over. It was obvious the victors might pose a threat, very possibly a military one, to Hong Kong. Lane Crawford's bread might at any moment be needed in another 'emergency'.

At the Executive Council Meeting of July 12, 1949 Lane Crawford won the day; Governor Grantham, accepting the advice of Council, allowed them to buy the land by private treaty at a stipulated price per square foot that was presumably significantly less than the public value. It was noted that it was important on security grounds that the company get the land quickly. It seemed that history in the context of the menacing events of 1949 had been decisive.

But there was an unexpected twist: the Council prudently added the proviso that any use of the land other than for a bakery needed Government approval – at which point Lane Crawford backed out, saying they would make 'other arrangements' for the bakery. No wonder the file includes a minute to the effect that they could expect to get the same treatment as everyone else in future. One can only wonder as to Lane Crawford's real intentions. The 'other arrangements' turned out to be... staying where they were! Company chairman F. C. Barry put an upbeat spin on the affair when he addressed the Ordinary Yearly Meeting on June 30, 1950:

A suitable site at any economic price for a new bakery could not be secured, and it was decided to reopen negotiations for renewal of the lease on our present premises. This has been successfully concluded and costly expenditure for land and buildings has, therefore, been avoided for the next five years at least. (22)

He also mentions money spent on installing new plant at the bakery, so the company clearly decided to go ahead with updating at least some of the machinery without the security of their own land. Interestingly he also announces settlement of Lane Crawford's long-term claim against the Department of National Defence (Army) Canada - I don't know if this is the hoped-for compensation referred to by Brown in the letter cited above, or why Lane Crawford had a claim against the Canadians.

Although in the end all it did was waste the time of Government officials at all levels, the way this application was dealt with casts a light on several aspects of Hong Kong in the late 1940s. It shows, first of all, the continuing importance of previous events, particularly those of the war: it's doubtful if the application would have got as far as it did without Lane Crawford's long presence in the Colony, its perceived usefulness in an emergency, and the particular service it gave during and immediately after the war. It's further evidence, if any is needed, of the justified nervousness of the British administration about the great events unfolding across the border. It's also an episode in the story of the 'racial' development of Hong Kong. The enterprising Cheung family, a mere four years after re-opening their business, were challenging one of the most important British companies, poaching one of their managers, and, in a society in which racism had been diminished but by no means completely eroded by the events of the war, had succeeded in reaching equal status with that company in the eyes of at least some government servants. Well, almost equal status: as we've seen, my father steps briefly on to the historical stage not for the excellence of his loaves but in his role as a 'European', whose presence gave Garden that little bit of extra credibility they needed to be taken as seriously as their rivals.

He didn't stay in Hong Kong for very long though. Although my parents never said so, I think it was the development of events across the Chinese border that made them decide to leave Hong Kong in early 1951– they would have returned to Britain at some point because they wished me to be educated in the system set up after the war, but, no matter how precocious I was, there was no urgent need to think about my formal schooling at the age of three months.

The real reason for our departure, I believe, wasn't familial. It turned out that the Communists felt that Hong Kong was worth more to them British than as part of the People's Republic, so there was no 'emergency' in late 1949 or in 1950. Nevertheless, the historical forces that had been set into motion by their victory were still setting the agenda for the Colony and its citizens.

At dawn on June 25, 1950 the army of North Korea crossed the border that divided the two Koreas and began an invasion of the South that saw them reach the outskirts of the capital, Seoul, the next day. The Americans quickly stepped in as part of the 'containment of communism' strategy, and this eventually elicited a response from Mao Zedong, who sent tens of thousands of 'volunteers' across the Yalu River. On October 25, less than a week before I was born, the Chinese forces attacked the western coalition, Stalin allowed Russian planes to lend air support, and the world faced the real prospect of another all-out war. One of the first actions in such a conflict would have been the taking of Hong Kong by the People's Liberation Army. Former prisoners of Shamshuipo and Stanley must have wondered if the horrors were about to return. My parents would not have wanted to enter such a nightmare again, made still worse this time by the presence of a baby.

A strong indication that this was the real reason behind the decision to move is the fact that my father had no job to go to in Britain, something he would have hated for more than purely financial reasons as he always welcomed hard work. Like so many others he'd lost everything in the war, and hadn't had time to build up any substantial savings – he later referred to our early years in Britain as a period when 'there was no food in the larder.' He had no choice but to take his family to live in his parents' large Victorian semi in Windsor. We stayed there for 18 months, sharing the house with his father, who'd never fully recovered his health after the First World War, and his mother, a woman of strong personality who'd been appointed one of the town's first Labour magistrates. But the Labour Giovernment had been in trouble for some time and it was to be out of office before my father had got his next job, bakery manager for the NAAFI in Portsmouth.

It was generally known that he was leaving some time before December 19, the day on which the Masonic Lodge he'd joined before the war elected him an Honorary Life Member. On January 23, 1951 we sailed from Hong Kong on H.M.S. Cyclops. The ship landed at London on March 7 and we disembarked into this different history.

* Any assertion not otherwise referenced can be assumed to be based on HKRS156-1-1460.

Particular reference is made to: Minute 210/3091/48; Memo of Jan 24, 1949; Letter of A. W. Brown to the Honorary Director of Public Works, 21 July 1948; Letter from Brown to MacDougall, Dec 22; 1948; Letter from A. W. Brown, Managing Director, 13 June 1949.Minute 210/3091/48; Memo of Jan 24, 1949; Letter of A. W. Brown to the Honorary Director of Public Works, 21 July 1948; Letter from Brown to MacDougall, Dec 22; 1948; Letter from A. W. Brown, Managing Director, 13 June 1948 See note* below).

* *In the notes I took at the PRO I dated this June 21, 1949. However, the content and the general context strongly suggest this was a mistake for 1948. However, it is just possible Brown was re-iterating his company's case ahead of the Executive Council meeting of July 1949. Nothing important hinges on the dating.

Notes:

1 The 'correct' form of the company name in the past was Lane, Crawford. I don't know when the comma was dropped and it was certainly not always inserted even in reliable pre-war sources.; http://blog.mobileadventures.com/2005/06/origins-of-hong-kongs-lane-craw...

2 https://www.google.co.uk/#q=origins+lane+crawford+hong+matshed+des+voeux

3 http://brianedgar.wordpress.com/2012/10/30/the-lane-crawford-bakery-in-s...

4 https://brianedgar.wordpress.com/2013/01/24/thomass-card-and-the-pains-o...

5http://brianedgar.wordpress.com/2011/10/21/two-pre-war-letters/

6http://brianedgar.wordpress.com/2012/04/08/thomass-work-5-the-siege-bisc...

7http://brianedgar.wordpress.com/2012/03/22/thomass-work-2-the-fighting/

8 https://brianedgar.wordpress.com/2012/08/19/the-french-hospital-arrests-...

9 http://brianedgar.wordpress.com/2012/04/30/thomass-work-6-post-war-recon...

10 https://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/stanley_camp/conversations/topics/2210

11 China Mail, November 8, 1946, page 3

12 China Mail, July 4, 1947, page 9

13 Hong Kong Telegraph, August 26, 1948, page 5

14 http://www.docstoc.com/docs/70317303/Imperial-Honours

15 China Mail, April 16, 1947, page 2

16) http://www.answers.com/topic/the-garden-company-ltd)

17 http://www.answers.com/topic/the-garden-company-ltd)

18 http://brianedgar.wordpress.com/2012/04/30/thomass-work-6-post-war-reconstruction/

19 Documents about the Ching Loong are in HKRS 114 DS6-335.

20The China Mail report (April 16, 1947, page 2) of the award ceremony claims that a Certificate of Merit was awarded to Ng Yiu Cheung (sic) of Lok Yuen Village in Shatin – the HKPRO file states he lives in Victoria and it seems that the reporter mistook him for one of the residents of that village who were being honoured for helping escapers. A preliminary report of February 16, 1947, (page 10) makes it clear that the award was to the man who helped Sheridan escape.

21 China Mail, August 27, 1949, page 2.

22 China Mail, 1950, July 1, 1950, page 4.

1925 Lane Crawford's Burrows Street Bakery