Photo (16): Queen Victoria’s statue

Primary tabs

Simmering cauldrons, steam cranes, and a disappointing statue all make appearances in this third extract from the new Gwulo book.

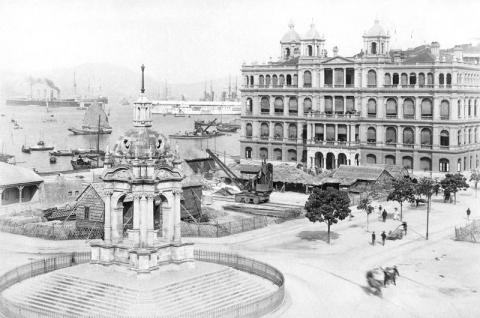

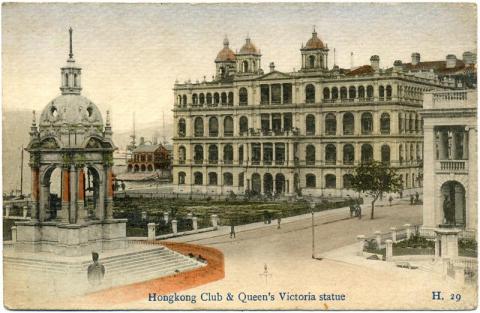

Hurley stuck with the patriotic theme, choosing a photo of ‘The Queen Victoria Jubilee Monument’ that was taken from Prince’s Building. Queen Victoria had died the previous year, ending a 63-year reign that began just a few years before Hong Kong became a British colony.

The monument, shown in the left foreground, was built to celebrate the Queen’s Golden Jubilee of 1887. It consisted of a stone shelter, housing a ‘disappointing’ statue of a seated Queen Victoria. The disappointment was due to a muddle in communication: Hong Kong thought it had ordered a marble statue, but the sculptor understood it was to be cast in bronze. The mistake wasn’t discovered until it was too late, so a bronze statue is what was unveiled in 1896. Victoria then spent the next four decades sitting peacefully in regal splendour, until the Second World War brought major changes.

After the Japanese victory in Hong Kong in 1941, the statue was shipped off to Japan to be melted down for use in Japan’s war effort. The stone shelter remained, but now housed a copy of a proclamation given by Hong Kong’s new Japanese Governor. In 1945 the British returned and the proclamation was quickly removed, but Victoria was considered lost forever, until … in 1946 the statue was found in ‘the murky shadows of the Osaka Army Arsenal’. It was returned to Hong Kong, but Victoria hadn’t been treated gently during her visit to Japan, so the statue needed major restoration work. By 1952 the restoration was all done, but by then the shelter had already been demolished ‘to improve traffic conditions’. Eventually the statue was re-erected in the new Victoria Park in 1955, and that’s where you’ll still find it today.

The patch of land behind the statue was known as ‘Hong Kong’s finest site’ in the 1910s and 20s, but back in 1902 it was a builders’ yard. In addition to its various sheds and stores, there was also this steam crane, set on rails that ran out to the water’s edge.

1902 was a busy time for steam cranes, as there’s another one on a barge near the centre of this photo, and a third in the centre of the cofferdam in the previous photo.

The grand building behind the steam crane is the Hong Kong Club, and hidden behind it is the club’s annexe that we saw previously. Though the annexe was still under construction, the main building shown here was already five years old. It was a much larger building than the old clubhouse on Queen’s Road, but though the members appreciated the larger accommodation, they weren’t very impressed with the view from their new front door. If it was bad in 1902, it would get worse – by 1909 the builders’ yard had also acquired a brick oven and two simmering cauldrons of coal tar, leading local businessman Mr Murray Stewart to complain about it at a Legislative Council meeting.

The Government replied that nothing could be done – Hong Kong was, as always, short of land, and there just wasn’t anywhere else to put it. Fortunately the new Law Courts, the last of the yard’s big construction projects, were nearly finished. The yard would soon be cleared away, and after being turfed the ground looked much more respectable.

Builders returned to the finest site in the early 1920s, but this time they met with no objections. They were working on Hong Kong’s new Cenotaph, which was completed and unveiled there in 1923. (See Volume 1, p. 28.)

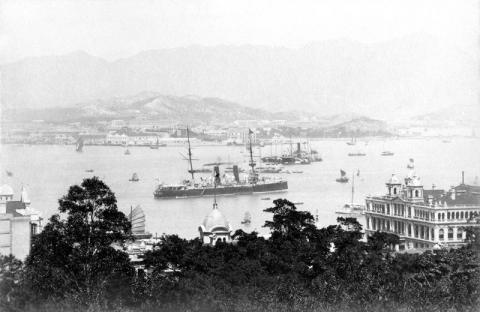

‘The Kowloon Peninsula’

In Hurley’s next photo, shown here, he wants us to look at Kowloon. Instead, look at the bottom left corner, where there’s an oddly plain wall, part of Prince’s Building. I say odd because, as the Hong Kong Club building has shown, plain wasn’t the fashion in 1902. The explanation is that this was an interior wall, not meant to be seen. Prince’s Building was bigger than its neighbours, and was built in several phases. We’ve caught it at the end of phase one, getting a rare glimpse of the wall before it was hidden by the next round of building.

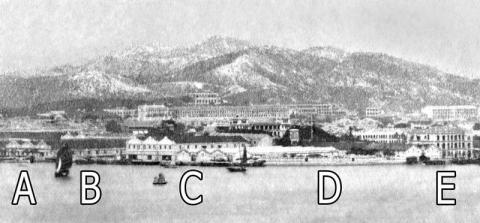

Looking right from the wall, in the centre foreground there’s a domed roof, but it isn’t Queen Victoria’s. Instead it crowned the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank’s building. At far right there’s the Hong Kong Club again, then look across the harbour to see Kowloon and Tsim Sha Tsui (TST). When we saw this area in 1886, TST was almost empty (Volume 1, p. 79). Here in 1902 there are plenty of new buildings to be seen.

(A) and (C) are warehouses for the Kowloon Wharves, separated by (B), a boat basin for the Water Police. Next there’s open land (D), then more buildings on the south shore (E). For a closer look at Kowloon’s development, we’ll leave Hurley’s album and turn our attention to some newer photos instead.

This photo and its story come from the third section of Gwulo's new book, Volume 4 of Old Hong Kong Photos and The Tales They Tell. The third section uses photos from an album produced in 1902, giving us an excuse to visit several well-known Hong Kong sites and see how they looked at the start of the 20th century.

Volume 4 of Old Hong Kong Photos and The Tales They Tell is available to order direct from Gwulo.

Further reading:

- Queen Victoria's statue

- Statue Square

- Hong Kong Club building and its annexe

- Cenotaph

- Prince's Building

- HSBC

- Kowloon Wharves

- Boat Basin

- South shore buildings

- More extracts from the new book

- Photo (4): Hilltop houses - The first extract from the new Gwulo book discovers that although this photo might look dull, its story has hidden treasure - literally!

- Photo (10): Pedder Street - Four buildings, a uniform, and a 'traffic stave' will pin down the date of the photo in this second extract from the new Gwulo book.

- Photo (19): Telephone House - The fourth and final extract from the new Gwulo book introduces Kowloon's first skyscraper.

Comments

Queen Victoria Statue

The idea of building a square to display royal statues in Hong Kong was concieved by Sir Catchick Paul Chater, prominent buisnessman and chairman of the Golden Jubilee Committee in April 1887, it was suggested by the committee that a permanent souvenir be provided by way of erecting a statue of Queen Victoria to commemorate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria. The staue was actually completed by the sculptor Signor M. Roggi in 1890 and was exhibited at the Horse Guards in London in 1891 and was forwarded to Hong Kong in the same year. However, it was kept in a storehouse for several years until the Praya Reclamation Scheme was completed. The statue was finally erected in Statue Square formally known as Royal Square in 1896 to celebrate the Queen's 77th anniversary of her birth.

The statue was erected on the base of 29 feet square and elevated about seven feet above the road level, the Queen is sitting facing Victoria Harbor and held a scepter in her right hand, while the orb and cross were rested in her left hand, the sceptor and orb were symbols of the nation and the rulers power. Since Britain was a sea power since the era of Queen Elizabeth I, and the British navy was the symbol of British strength, hence the implication of the statue facing the sea (harbor) that the Queen was the ruler of the sea.

"Covered by dome, the whole being a most fitting adjunct, stands a bronze image of Queen Victoria, erect and holding the sceptor and globe that typically the powers she so ably wields. the entire structure fitly represents the feelings of love and loyalty felt by her subjects in this colony, who by her wise and just rule have been anabled to erect upon this bare and rocky island". (The Hong Kong Telegraph 28th May 1896)