A John Bowring 'Trail' in Exeter - Part 2

Primary tabs

A John Bowring 'Trail' in Exeter

by Brian Edgar and James Turner

Part 2

When James and I had finished looking around the Bowring family's place of worship...

Copyright Derek Harper and Licensed for Re-use under this Creative Commons Licence

...we settled down to talk about John Bowring's time as Hong Kong Governor over a coffee - luckily George's Meeting Place is now a Wetherspoon's pub and restaurant:

Brian: James, you've been telling us some of the ways in which John Bowring was shaped by his childhood in the Exeter wool trade and his Unitarian experience with his family and here at George's Meeting House - could you take the story forward to his time in the Far East.

James: Bowring's finances suffered badly in the economic collapse of the late 1840s so when the Prime Minister, Palmerston, offered him the job as Consul and Superintendent of Trade in Canton he accepted at once. His son John Charles had gone to China in 1842 and this had perhaps reminded him of that family connection through the wool trade - he served on a Parliamentary Committee on China and spoke on Hong Kong in the Commons. He went out to Canton in 1849 and stayed there until 1853. During that time he clashed frequently with Yeh Mincheng, the city Commissioner:

Commissioner Yeh Mincheng (Image: Wikipedia)

Brian: And that experience I think lies behind his role in helping start the Second Opium War. The British had forced the Chinese to allow the sale of Indian-grown opium as part of the Treaty of Nanking at the end of the First Opium War in 1842, the time they also acquired Hong Kong Island. Ironically, Bowring had been an outspoken critic of that conflict, arguing that you couldn't promote trade by war!

James: One of many 'Bowring paradoxes'!

Brian: Yes, indeed. In the 1842 Treaty the British also got the right to trade freely at four ports in addition to Canton - up until then the Chinese had insisted that this was the one place western merchants were allowed to do business. In the following years, the British sought to take full advantage of the new trading opportunities – when Bowring visited Shanghai, one of the new Treaty Ports, he saw a Chinese administration happy to co-operate with European traders. But in Canton the authorities were obstructive, and he was caught between them and a crowd of pushy opium traders. I think Bowring became impatient with the Chinese during this period and in some way started to cherish the idea of forcing them to enjoy the benefits of free trade!

James: The very thing he'd said was impossible in the early 1840s.

Brian: Right. Bowring did a stint as 'temporary Governor' of Hong Kong in 1852 when George Bonham was on leave. He obviously did well enough to get appointed fourth Governor in 1854.

Brian: That's right. But I think before that happened he had an experience that maybe helped convert him to what came to be called 'gunboat diplomacy'.

James: You mean the 1855 trade treaty with Siam? ((Now Thailand.))

Brian: Yes. On the one hand, this was imposed on Siam, which had already been threatened by British gunboats. Bowring sailed in with a couple of warships, which no doubt hammered home the point as to what would happen if no agreement was reached. But he'd already built a personal relationship with King Mongkut, and the Treaty, unfair as it was in some ways, did benefit both sides, as Bowring believed free trade always would – Siam became one of the main suppliers of rice to Hong Kong, for example. King Mongkut obviously appreciated Bowring's actions because he made him Siam's Ambassador to Europe during his retirement in Exeter.

King Mongkut of Siam (Image: Wikipedia)

James: So Bowring was maybe encouraged to think he could work the same trick with China?

Part of the ruins of the Summer Palace (Image: Wikipedia)

Brian: It seems that Bowring knew that he was on shaky ground legally – the Arrow's British registration had run out, for example, and the fact that the Chinese crew probably were pirates. But I wonder why he was so eager for conflict? James, let me play Devil's Advocate here. His critic, Karl Marx, wouldn't have been in any doubt: Jardine Matheson, the biggest opium traders, were linked to Bowring's bankers, and his son John Charles - the one whose house we visited – was one of their directors... Surely Marx would have grunted disdainfully if you suggested that we should consider any other motive than personal economic interest for Bowring's warmongering.

James: Sure, financial motives must have influenced him, but I don't think very strongly. We should also remember he was a patriot, as almost all men of his class were - for all his forward thinking ideas, he was also a man of his time. He wrote that the bombardment of Canton and the forcible entry to the city were 'more worthy of a Great Nation than the stoppage of duties and disturbance of trade.' In other words, force was more 'worthy' of a Britain at the height of its power than mere economic sanctions. But remember that free trade was always one of Bowring's guiding beliefs and he was quite sincere about this - he thought it would help everybody. He was also someone who wished to be seen as an achiever of great things. Put the two together and you can say that he wanted to be the man who had solved the long-running problem (from the British point of view) of opening China to western trade on as free a basis as possible. He didn't invent the problem himself. But he went about his task clumsily and without regard to the rights of the Chinese.

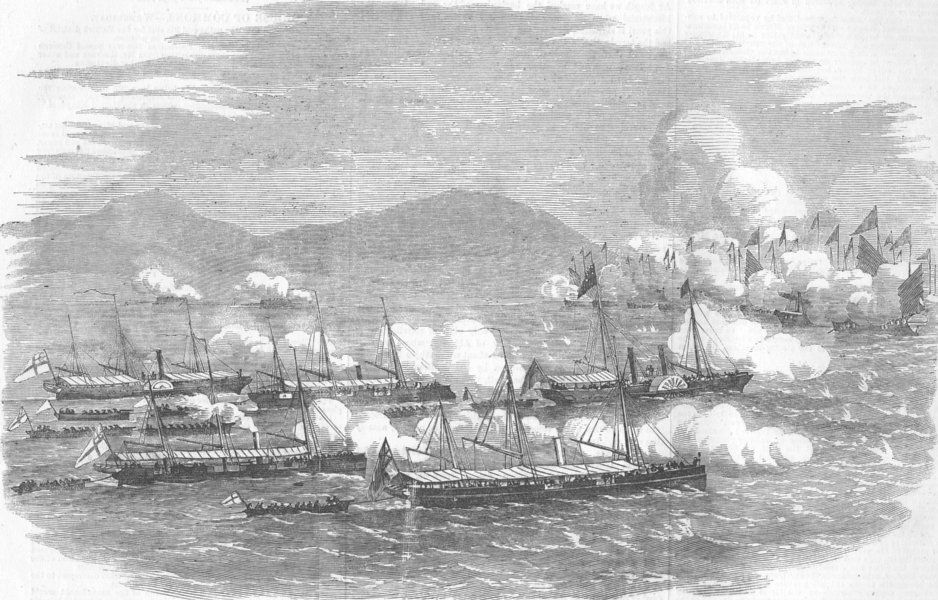

British gunboats burning Chinese Junks, 1857 (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Suburbs of Canton Burning, 1857 (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Brian: Yes. The British expected that the trade with China, which was very important to national and Imperial finances, would grow after 1842, but British exports there were actually less in 1848 than in 1843. There was pressure on Bowring from London to open up commerce as much as he could, although not by using force. His frustration led him to betray his internationalism and develop some racist views about the Chinese which contributed to his actions in 1856. But we should also remember that he was far more respectful of the Chinese than many others in the diplomatic service: he wrote a long essay on Confucius, for example, and he recommended that consular officials be trained in Chinese before being sent to their posts.

Brian: But sadly Governor Bowring had a strange set of blind spots for an internationalist and a peace lover.

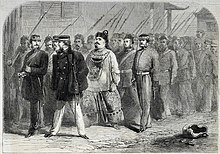

James: Yes, and personal vanity was involved too. He wanted to sort out the Arrow problem by meeting Commissioner Yeh, but only if Yeh received him in proper fashion, grandly and in his own yamen ((official residence)). He insisted that the demand for this meeting must be made 'in the presence of ships of war.' The meeting never took place, and Yeh ended up starving himself to death as a prisoner in British India.

Commissioner Yeh's capture after the fall of Canton (Image: Wikipedia)

Brian: I think vanity was a part of his character that a number of people noted. But there's something else to be said in Bowring's favour. During the war there were proclamations in Canton which asked Hong Kong Chinese to help in the fight against Britain, and there was an attempt, perhaps inspired by these pleas, to poison the British community by putting arsenic in their bread. However, such huge amounts of the poison were used that the British – some of whom had been warned by their Indian servants who also ate bread and breakfasted first – didn't die but just got very ill. None more so than Lady Maria Bowring, who probably died in 1858 from the long-term effects of her dose. Bowring was asked to declare martial law and take stringent measures but he refused to panic. The baker - Zhong Alum - had fled to Macao with his family that morning and when he was brought back to Hong Kong Bowring insisted he got a fair trial.

James: Not looking good for Zhong Alum at this point.

Brian: Nevertheless, he was acquitted, and that fact was actually important in Hong Kong's future history. Later colonialists looked back to the case and thought, 'We British Hong Kong-ers are like that – someone tries to kill us all and we don't lynch him – we put him before a court of law and let it decide according to the evidence.' And this kind of thinking actually led to a legal system which although racist and biased against the Chinese was better than it would otherwise have been. So even in all the nastiness of the Second Opium War, something good emerged for Hong Kong's majority population. I should also mention in passing that it was Bowring who allowed Chinese people to become lawyers and to serve on juries, two more things that made the courts fairer. His legacy also includes water and building ordinances. He didn't spend his five years doing nothing but foment war. And ironically by the time he left Hong Kong in 1859 he was popular with the Chinese and much hated by the British.

James: We could put that down as another paradox given that most of the British had welcomed the war.

Brian: Another 'legacy' Bowring left to Hong Kong was his daughter Sister Emily who became headmistress of the Italian Convent School.

James: A number of Bowring's children converted to some form of Catholicism. Maybe they were reacting against the rather austere rationalism of their childhood Unitarianism. And two of his sisters became Anglican and swapped George's Meeting House for the Cathedral.

Image: Wikipedia