Hong Kong surprises in the National Archives

Primary tabs

Finding what you weren't looking for is part of the fun of a visit to the archives. Here are a few surprise finds from a visit to the UK's National Archives last month:

Refractory women on Kellett Island

The description of item WO 44/98 [1] looked relevant to the rusty iron water tank quest. Turns out it wasn't, but as I skimmed through it this caught my eye:

"The Barrack Master has [unclear] to state, as one cause of the state of disrepair of the small Barrack at Kellett's island, that it has been occupied by some refractory women of the 18th Regiment, who had been placed there by the Assist. Adjud. General without the knowledge of or any previous communication with the Barrack Master."

It was written in 1844, so it's the earliest reference to Kellet Island [2] I've read. I didn't expect to find it being used as a mini-Alcatraz!

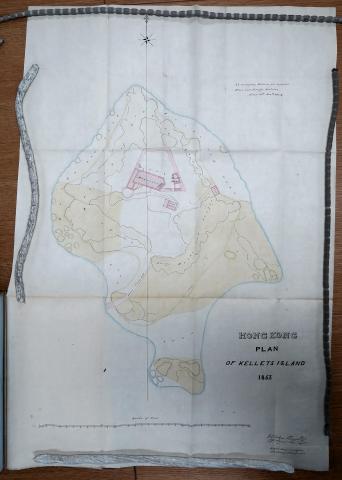

Another document, WO 55/2962 [3], has several maps at the back including this detailed map of Kellett Island as it looked in 1853. By that time the main building on the island was a magazine to store explosives:

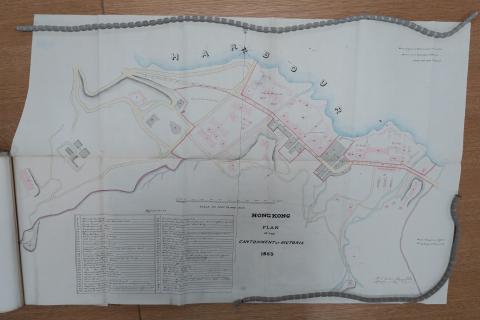

The other two maps in that document show "Military Cantonments", ie military camps, in 1853. The first shows the "Cantonment at Victoria" - the area we know as Admiralty today [4]:

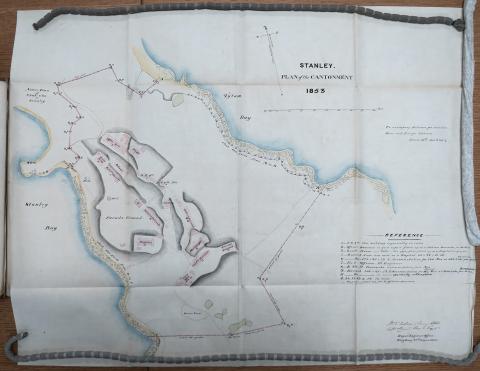

The second shows the army's buildings at Stanley [5]:

The army buildings at Stanley haven't survived, but at the bottom of the map is a small patch of land marked "Grave Yard". Those early graves and their gravestones are still there today, now part of the current Stanley Military Cemetery [6].

Re-starting Hong Kong in 1945

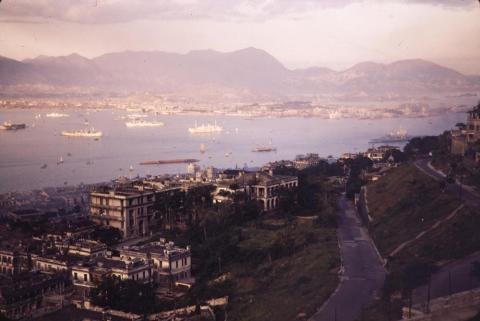

Klaus recently posted a couple of photos taken from "W.A.D. Brook's Air House" in November 1945:

Air Commodore W A D Brook was in charge of the RAF in Hong Kong at the time. The airmen were busy helping Hong Kong get back on its feet after the war.

I wondered if the archives would tell us anything about the house he took the photos from, which led to "Occupation of Hong Kong: reports by Air Commodore W.A.D. Brooke. Date: 1945 Aug.-Nov." [7].

He does mention his house:

"My own house was the residence of the Japanese Chief of Police, a very well built modern house overlooking the harbour with a bathroom to every bedroom and every modern inconvenience [sic.]."

And also made another couple of good observations of the situation at that time:

"As you might imagine there was a general spread of enthusiasm as most people were doing jobs they had never dreamed of and making a good show of it. One of my officers, a fighter pilot, was a Governor of a Jap concentration camp in which some 10,000 were incarcerated, including at least three Generals and one Admiral."

"We have done very well with the [Hok Un] Power Station [8], where we had to alter the fuel burners from coal to wood and back again in relation to the fuels that were available, from time to time. All this has been done by a very small body of personnel including a Lancashire boilerman who, when I complimented him on his efforts, said that "there's nowt much to it", and he had had worse jobs to fix up back in Wigan."

RAF Little Sai Wan's camp's magazine, c.1957

I took a look at the Operations Records Books for RAF Little Sai Wan [9], hoping to learn more about their listening operations. Instead the records are very dry, covering topics such as "Health & Welfare", "Distinguished Visitors", and the other minutiae of running a camp.

The pleasant surprise in this case was a copy of the camp's magazine, "Ariel", filed along with the more usual paperwork:

I enjoy seeing the adverts in old magazines:

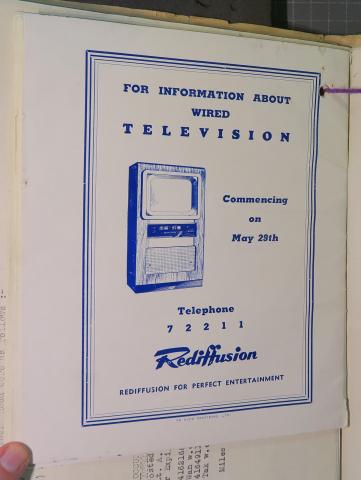

The magazine doesn't have a date, but looking at the Rediffusion advert above I guess it was from early 1957, as that was the year they launched their cable television service in Hong Kong. Hopefully the TV would take the airmens' minds off the service in their canteen:

First use of radar to detect rainfall

In the rainy time of year, the Hong Kong Observatory's online Weather Radar [10] is my best friend. It shows the bands of rain approaching Hong Kong, so I can time outdoor dashes to catch the dry spells. One surprise was how early this technology was first used in Hong Kong - 1946!

That snippet came from reports about the AMES in Hong Kong. The AMES, or "Air Ministry Experimental Station", was the original name for the RAF's radar stations. Several operated in Hong Kong, and the rain radar report came from the AMES at RAF Kai Tak [11][12]:

"2 Mar 1946: Several [unclear] were plotted during the morning and full information was passed to the Met. Section at Kowloon Observatory. Doubt was expressed as to the existence of nearby rain clouds, but shortly afterwards the district was swept by a heavy rainstorm which flooded the technical site. The Observatory was impressed, and [...] a system of liaison and regular reporting was commenced."

Another AMES report that mentions the weather came from the AMES up at RAF Tai Mo Shan [13][14]. Not such good news though, it describes the miserable start to their time in Hong Kong:

- 1 Mar 1946: Camp enveloped in dense mist for the 5th successive day.

- 2 Mar 1946: 60 mph gust of wind blew off the parabolic reflector and smashed it irrepairably.... Main electrical supply failed. Petrol electric standby generator in use.

- 5 Mar 1946: Standby generator failed, camp now lit by hurricane lamps.

Living standards improved over time, so that by September 1950 reports from the AMES on Mount Davis [15][16] list regular film shows:

- 7 Sep 1950 "Now Barrabas was a Robber"

- 18 Sep 1950 "The Bishop's Wife"

- 21 Sep 1950 "Nightbeat"

- 26 Sep 1950 "Unfaithfully Yours"

I'd requested these documents from an interest in the AMES over at Ping Shan [17]. It was the radar site nearest to the border with China, and their reports [18] show that apart from the film shows and weather services, there were times when the radar was used as originally intended:

"December 1949: Several Chinese Nationalist transport aircraft were intercepted during the month, mostly outside the Colonial boundary. [...] Raid Reporting tracks have fallen almost by half. In the main due to the grounding at Kai Tak of all non-defected Chinese National Airways Corporation and Chinese Air Transport Corporation aircraft. [...] Order 13/49 was received ordering the unit on to a 24 hour operational basis on receipt of the executive signal. This is a precautionary measure to counter any possible hostile action by the Chinese Nationalist Air Force if an when Great Britain recognises the Chinese Peoples Government as the Government of China."

This has turned out longer than I expected. I'm still only half way through, so I'll stop here and send out the second half in a few days time.

If you're visiting London and you're interested in Hong Kong's history, I recommend a visit to the National Archives. They're easy to get to, just a short walk from Kew Gardens Underground station. Here are details of how to prepare for a first visit.

|

Readers ask for information (photos, facts, memories, etc.) about:

New on Gwulo.com this week:

|

References:

- 1844: Disputes with Ordnance. UKNA ref: WO 44/98

- Kellett Island

- 1851: Ordnance Office and War Office: Miscellaneous Entry Books and Papers. Lands and Buildings Owned and hired by the Ordnance -. Statements of Lands and Buildings... Hong Kong. UKNA ref: WO 55/2962

- Why is Admiralty different?

- Stanley Military Cantonment

- Stanley Military Cemetery

- 1945 Aug-Nov: Occupation of Hong Kong: reports by Air Commodore W.A.D. Brooke. UKNA ref: AIR 20/5485

- Hok Un / Hok Yuen Power Station [1921-1991]

- 1956 Jul- 1959: Dec Air Ministry and Ministry of Defence: Operations Record Books, Royal Air Force Stations. LITTLE SAIWAN. UKNA ref: AIR 28/1331

- Hong Kong Observatory Weather Radar Image

- 1945 Jul - 1946 May: No. 15069 AMES Kai Tak. UKNA ref: AIR 29/194

- RAF Kai Tak

- 1945 Jul - 1946 Jun: No. 5097 AMES Tai Mo Shan. UKNA ref: AIR 29/187

- RAF Tai Mo Shan

- 1946 - 1950: No. 21022 AMES Mount Davis. UKNA ref: AIR 29/1941

- RAF Mount Davis

- RAF Ping Shan

- 1946 - 50: No. 15138 AMES Tai Ping Shan. UKNA ref: AIR 29/1944

Comments

Who were those "refractory women"?

Guy Shirra replied by email:

Surely they could not have been officially attached to or be the wives of "the 18th Regiment"? Were they comfort women perhaps or camp followers from China expeditions, tucked away from prying HQ staff?

I hadn't thought about who the women were. As Guy says, it seems very unlikely the soldiers' wives would accompany them on such a long journey to an area known for its high mortality among soldiers.

But searching for more information, it turns out that not only did the soldiers' wives accompany them, their children came too!

The following extract comes from pages 142-3 of "The campaigns and history of the Royal Irish regiment from 1684 to 1902" and covers the years 1843-44. (The "18th Regiment of Foot" changed its name to the "Royal Irish Regiment" in 1881. I've added the bold below.):

At the opening of Parliament in 1843, the House of Lords passed the usual vote of thanks to the troops which had taken part in the campaign. A medal was issued to the officers and men who had served in the Chinese war; leave was granted to the XVIIIth to add to its other battle honours the word “China” and the device of the Dragon, and Colonel G. Burrell, Lieutenant-Colonel W. H. Adams, and Majors J. Cowper and J. Grattan were awarded the C.B.

Very disagreeable orders awaited the regiment on its arrival at Chusan. Four companies were to remain there as part of its garrison until the Chinese had fulfilled all the obligations of the treaty, while headquarters and the greater part of the regiment were to occupy the island of Kulangsu, which our Government also held as a pledge of Chinese good faith. Kulangsu had already acquired the reputation of being one of the most unhealthy stations in China, and the Royal Irish soon discovered that its evil reputation was but too well deserved. According to Lieutenant-Colonel Graves’s statement, when the headquarters companies landed they found the detachment of the regiment which had been there for some months in a deplorable condition. There had been many deaths among all ranks; every one of the surviving officers was down with fever,

“ and there were not thirty men under command of a sergeant who were fit for duty or could shoulder a firelock. . . . When the Headquarter companies landed from Chusan the men were healthy and well seasoned, but they very soon began to feel the climate, and before long half the men were on the sick list, and we began to bury them very fast. I had been appointed Staff Officer for the island, and at first found much difficulty in getting coffins quick enough, so I ordered twenty at a time to be supplied by a contractor at Amoy. Several of our officers died, and at last I found much difficulty in getting men enough to relieve the guards. I went to our Colonel, Cowper—who was the Commandant of the island—and represented that if we did not get a ship sent up from Hong Kong for the invalids we should very soon have no men for guard. We got a ship and found her of the greatest benefit; she was anchored half a mile out of the harbour, and the invalids sent on board her came back in a week fit for duty.

“A large draft joined from England, about three hundred strong, together with the women and children. This caused a little stir, but it was a short-lived happiness: they went down almost as fast as we could provide coffins for them. We pitched tents and moved our camp daily about the island, but it was no use—cholera and fever still continued. The men began to drink to drown dull care; the officers off the sick list were constantly on Court-Martial duty, and the Colonel received an official letter from Headquarters drawing his attention to the number of Courts-Martial for drunkenness, and directing him to parade the regiment and reprimand the men for their conduct, which was alleged to be the principal cause of the severe mortality. As Staff Officer and adjutant of the regiment I was ordered to read this letter to the men, which I began to do, but I must acknowledge I fairly broke down and had to hand it to another officer to finish. I felt so keenly how our gallant poor fellows were being sacrificed, after their long, hard services, to a climate no one could live in, and how they bore it!"

In April 1844, after a hundred and thirty-six officers and men (6 officers, 6 sergeants, 6 drummers, and 118 rank and file) had fallen victims to the climate of Kulangsu, the regiment was reunited at Chusan. The next station was Hong Kong, where the ordinary routine of garrison life in the East was suddenly broken by an urgent and wholly unexpected call to arms. The people of Canton, always overbearing and offensive towards Europeans, had recently insulted and ill-treated British subjects, and their Mandarins had refused to make redress for the outrages. The British Plenipotentiary, Sir John Davis, was a believer in the saying “A word and a blow, and the blow first," and he determined to teach the mob of Canton a lesson they would not soon forget. During the night of the 1st of April, 1847, the Royal Irish, under Lieutenant-Colonel Cowper, with 23 officers and 509 other ranks, and the 42nd regiment of Madras Native Infantry, 399 strong, were packed into a couple of small men-of-war and an armed steamer. Early on the following morning the flotilla was off the entrance to the Canton river; the troops were landed, and driving the Chinese artillerymen from the batteries, spiked the guns. The works higher up the stream were then treated in the same way, but not without vigorous opposition from the enemy, whose aim, however, was much distracted by the steady fire of a party of the Royal Irish, described in the despatches as the “acting gunners of the XVIIIth, who replied to the batteries in a style which would have done credit to experienced artillerymen.” As soon as the ships were off Canton the soldiers occupied the “factories”; placed them in a state of defence, and made plans for storming the town. The Royal Irish were looking forward to winning much glory (and much prize money too) in the capture of Canton, when the Mandarins, greatly perturbed by Sir John Davis’s prompt reprisals, hastily made full atonement for their misdeeds, and the expedition returned to Hong Kong. They had done a good week’s work: 879 guns, many of great calibre, had been spiked, much ammunition destroyed, and a greatly needed lesson given to the Canton roughs—and all without the loss of a soldier, bluejacket, or marine.

General D'Aguilar, who was in command, mentioned in his despatch the following officers of the regiment, viz., Lieutenant-Colonel Cowper; Captain J. Bruce, A.A.G.; Captain Clark Kennedy, Acting A.Q.M.; Captain J. W. Graves; Captain A. N. Campbell, and Lieutenant E. W. Sargent, Acting A.D.C.