Po Kong village [????-1942]

Primary tabs

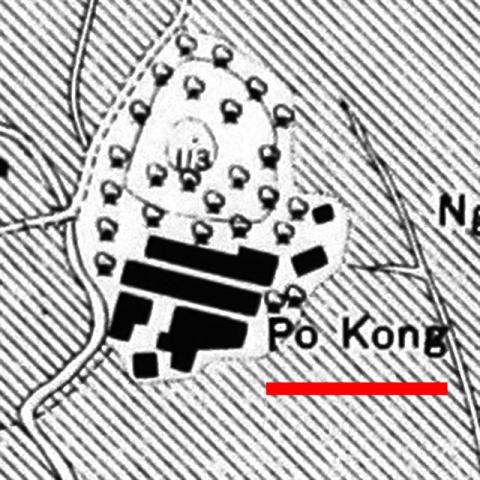

Last November we moved to San Po Kong (新蒲崗) in Kowloon. The "San" means "New", so I wondered if there was an older Po Kong that it takes its name from. A map of the area from 1902-3 [1] shows the answer is yes: there was a village named Po Kong.

Po Kong village and its surroundings

The map shows the village was in the centre of an area of flat, low-lying farmland. It also gave its name to the nearby Po Kong cemetery [2], probably the open area to the southeast of the village, marked on the map with crosses.

On the map, Po Kong looks like one of the largest villages in the area. But these figures from 1899 [3] show it was just mid-sized, with a population of 80.

| Name of Village | Population | People |

| Chuk Un | 80 | Punti |

| Kak Hang Tsun | - not listed - | - |

| Nga Iu Tau | - not listed - | - |

| Nga Tsin | 150 | Punti |

| Po Kong | 80 | Punti |

| Sha Ti Un | - not listed - | - |

| Shek Ku Lung | - not listed - | - |

| Ta Ku Ling | 150 | Hakka |

| Tai Tan Tsun | - not listed - | - |

| Un Ling | 200 | Punti |

Here's a closer view of the village:

It had the typical layout for a village in this part of the world, with a couple of terraces of houses, and a forested hillside (likely a fung shui wood) behind it to the north. You can still find villages with this layout in more remote parts of the New Territories.

Life in the village

I haven't seen any photos or reports on what life was like there, but we can glean some ideas from government reports.

Po Kong appears in several of the annual police reports, showing that fire was a risk to its residents:

- 1912: There was a fire at House No. 8 Po Kong Village [4].

- 1915: A suspected arson attack set fire to a matshed, killing a boy and two women [5].

- 1937: Two more people died when a house in the village caught fire [6].

Another risk was malaria, as all that wet farmland around the village made good breeding grounds for mosquitoes. When the British Army tried to set up a camp for 200 soldiers at nearby Chuk Un in 1928, 80 of them were infected in the first month [7]. The camp was swiftly abandoned.

Changes in the early 20th century

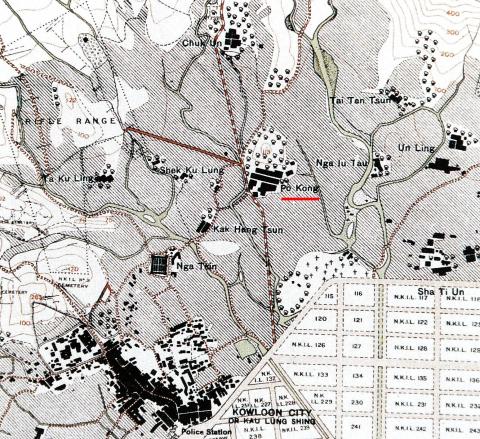

The lease of the New Territories in 1898 put Po Kong under British administration for the first time. Some of the changes that followed are shown on this map from 1924 [8]:

Communications had improved since the earlier map, with several new paths and roads meeting at Po Kong village. The straight road leading off at 10 o'clock from the village had been built in 1910, and was a "six-foot path [...] constructed by the military authorities to connect their Rifle Range with the Sha Tin Road at Po Kong" [9]. The striped road heading roughly north-south is the road up to Sha Tin Pass.

There were changes at the Po Kong cemetery too, with a 1915 report telling us that "Consequent upon the closing of this cemetery, considerable exhumations were carried out under the direction of the Head of the Sanitary Department. The area occupied by the cemetery, which is near Kowloon City, will be required in connection with the development of the district." [2]

The development they had in mind is clear to see at the bottom of the map. The Kai Tak Bund reclamation [10] was a large area of new land, with dotted lines on the map showing the proposed grid of streets. The project was started by Kai Tak Investment Company, but they ran out of money before the work could be completed. That left a large, empty, flat piece of land - perfect for use as an airfield. In 1925 a flying school started operating there, the beginnings of what would grow into Kai Tak airport.

1930s Trouble brewing

Back to the government records, where the 1931 police report shows Po Kong got caught up in the growing conflict between China and Japan.

"Generally speaking, the year would have been considered a good one, had it not been for the serious Anti-Japanese outbreak at the end of September which was accompanied by rioting, a certain amount of looting of shops storing Japanese goods and the dastardly murder of a Japanese family at Tsang Foo Villas in the Kowloon City District. [... On Saturday, 26th September,] murder had been committed at an isolated Villa at Po Kong, a mile from Kowloon City where six out of the eleven inmates were brutally done to death." [11]

Were the British also thinking of conflicts ahead? The mentions of malaria above come from a 1933 report by the Malaria Bureau [7]. The area they investigated was described as the "Proposed Site for Cantonments at Po Kong". A Cantonment is a military camp, suggesting the British Army had plans to develop a camp in the area, possibly in conjunction with developing the RAF facilities at Kai Tak.

The army didn't move in, and a report from 1939 [12] still describes the land around Po Kong as the "large market garden area". Despite the changes going on around them, the villagers must have felt that their farming lifestyle would continue unchanged. They were wrong.

The end of the village

The first warnings of change came in the morning of 8th of December, 1941, when Japanese planes bombed Kai Tak. Residents of Po Kong would have seen and heard the nearby explosions. They probably breathed a sigh of relief when the British surrendered and the fighting ceased, but the villagers' troubles were just beginning.

The Japanese wanted to expand Kai Tak airfield both north and south. Any villages within that area were to be removed, and their farmland converted to airfield. Po Kong and its wooded hill both lay within the boundary of the planned expansion.

Reports from the the agents of the British Army Aid Group (BAAG) [13] trace Po Kong's destruction:

- 24th June 1942: "The Japanese are apparently extending the air field and reports quoted in the local press say that it is intended to make it four times its present size."

- 10th July 1942: "Work has started on the extension of the airfield at Kai Tak. Houses in the vicinity must be demolished by occupants forthwith, compensation HK$1,000."

- 14th September 1942: "All the houses in the Po Kong Village have been pulled down."

So less than a year after the Japanese occupation began, the village was gone. It appeared that the hill was next, as the Japanese also needed material to use as landfill for the reclamation to the south:

- 14th April 1943: "Earth diggings. Firstly, a greater portion of the hill at Po Kong has been removed. It is estimated that the whole thing will be completed by June."

Po Kong's hill survives

But the Japanese never did excavate all of the Po Kong hill, likely because they recognised its value. Tucked away in the northern corner of the new site, the higher ground gave them a good vantage point to look out over their expanded airfield.

So instead they kept the hill, and built this upside-down-"T" shaped building on it.

We're still looking for hard evidence about what the building was used for, with one possibility that it was their control tower [14].

That building wasn't demolished until some time in the late 1950s / early 1960s, after which the hill became part of the new Kai Tak amusement park [15]. In time the amusement park disappeared too, but the hill still stands, now part of the public Choi Hung Road Playground. You can see it on the left as you drive west along Choi Hung Road:

Legacy of Po Kong village

Apart from the remains of its hill, the village also lives on in a couple of local names: Po Kong Village Road, Po Kong Village Road Park, and of course San Po Kong.

It would be great to learn more about the village and its hill, so please leave a comment below if you can add any photos or stories.

Regards, David

References:

- Plate 4-3, Mapping Hong Kong.

- Exhumations are noted in item 179 of the REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC WORKS FOR THE YEAR 1915.

- The 1899 populations of the villages are shown in the KAU LUNG DIVISION section of Appendix No. 5 of Extracts from a REPORT BY Mr STEWART LOCKHART ON THE EXTENSION OF THE COLONY OF HONG KONG.

- Fire reported on page J22 of the REPORT OF THE CAPTAIN SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE FOR THE YEAR 1912.

- Fire reported on page K23 of the REPORT OF THE CAPTAIN SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE FOR THE YEAR 1915.

- Fire reported on page K (1) 7 of the REPORT OF THE COMMISONER OF POLICE FOR THE YEAR 1937.

- The investigation of malaria at the "Proposed Site for Cantonments at Po Kong" is described on page M158 of the MEDICAL & SANITARY REPORT FOR THE YEAR 1933.

- Plate 4-4, Mapping Hong Kong.

- Section X.-PUBLIC WORKS of B.-SOUTHERN DISTRICT in the 1910 REPORT ON THE NEW TERRITORIES.

- Kai Tak Bund reclamation

- Attacks against Japanese reported on page K2 of the HONG KONG POLICE ANNUAL REPORT FOR 1931.

- The "market garden" is mentioned on page N9 of the REPORT OF THE BOTANICAL AND FORESTRY DEPARTMENT FOR THE YEAR 1939.

- Extracts from the BAAG's reports about Kai Tak have can be viewed online at The Industrial History of Hong Kong Group website.

- Discussion about the location of the Japanese control tower at Kai Tak.

- Kai Tak amusement park.

Comments

Po Kong Village Road

Interestingly, today's Po Kong Village Road is on the other side of Choi Hung Road and quite a bit far up the hill from Hammer Hill Road. I wonder if PKV was still around when PKV Road was built.

Re: Po Kong Village Road

It is noted here that the villages in the vicinity of Po Kong had formed inter village "alliances" for mutual protection during the Qing dynasty. Not sure if the villagers of Po Kong were relocated to other villages nearby during the expansion of Kai Tak Airfield or Po Kong Village Road was named as a historical reminder of the former village that used to exist in present day San Po Kong.

Cemetery relocation near Kai Tak

Interesting to note the sensitivity of the HK Govt in 1915 in exhuming and presumably relocating past burials at Po Kong.

I seem to recall that in the 1940s-50s it was said that the prewar HK Govt had been very reluctant to attempt to resume a cemetery adjacent to the airport, which would have enabled the necessary expansion.

The Japanese administration in 1942 had no such qualms, and expanded roughshod, which saved the postwar Govt a few headaches.

Re: Po Kong Village Road

I guess the road was named when the village was still around. If you visit http://www.hkmaps.hk/mapviewer.html and select overlay "Map 1945", there is a road that runs northeast from Po Kong Village along roughly the same line as today's Po Kong Village road.

Evacuation in 1939

A reply to this post on Facebook has a clipping from a Chinese newspaper, and a note that it shows "force evacuation of the village 1939". Please can anyone help translate it? It's at https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10213802289665955&set=p.10213802...

Regards, David

incident in 1939 Po Kong Village

According to the news article (June 17, 1939), it is a private land owner of a site in Po Kong Village who wanted to resume the land. This affected some three hundred inhabitants who had rented the land and built their own homes there for more than tens years. They went to the govt (華民政務司) to ask for help.

Apparently, such "forced evacuation" or rent hikes were quite rampant at that time in HK. The article said the govt had legislated to stop forced evacuation, but it seemed to be largely ignored.

re: incident in 1939 Po Kong Village

Thank you for the translation. I'd wondered if the article was about the British government wanting the land for an airfield extension, so it is good to have it explained.

From Wiki:

From Wiki:

「蒲崗」之名是「蒲田」和「山崗」的結合,分別指開村村民祖籍及該地地形,原址爲新蒲崗西北角的彩虹道遊樂場一帶。蒲崗村於1942年被侵華日軍拆毀,村民被驅散,蒲崗山被削去大部分。戰後蒲崗村舊址附近發展出新的住宅及工廠區,命名爲「新蒲崗」。

Brief translation:

The name of "Po Kong" is the combination of "Po Tin = farmland" and "Shan Kong = Hill". The original location is around the Choi Hung Road Playground. Po Kong Village was destroyed by the Japanese invasion in 1942 and a large portion of the hill was removed. The area of the new residential and industrial area nearby is named as "New Po Kong" thereafter.

Clans in the Po Kong Village

According to Tai Kwok Wah(戴國華), a descendant of Tai Shi Fan(戴士蕃)who built the Tin Hau Temple in Causeway Bay, there were at least three clans in the Po Kong Village, namely, Tai, Yau (邱)and Tsang(曾). The Hakka Tai clan later moved to Causeway Bay.

References:

1. 鍾寶賢:《商城故事:銅鑼灣百年變遷》(香港:中華書局,2009),頁51、53、56。

2. https://www.amo.gov.hk/en/monuments_15.php