Shipbuilding in Hong Kong – Hongkong & Whampoa Dock Company

Primary tabs

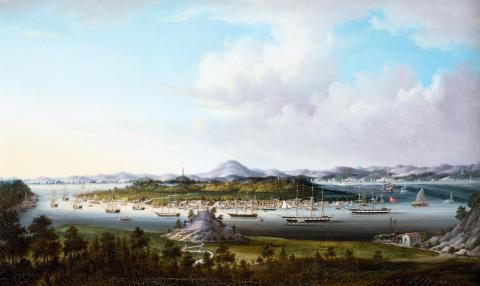

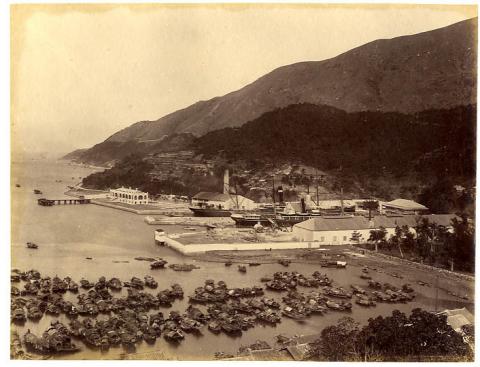

Both Gwulo and the Industrial History of Hong Kong Group have a number of posts on various aspects of the history of the Hongkong and Whampoa Dockyard . This contribution as a ‘forum topic’ seeks to provide some more pictorial information about the company’s early origins in Whampoa ( Huangpu黃埔), the Canton (Guangzhou) anchorage for foreign trading ships entering the Pearl River. I am also posting photographs with brief information about some of the ships built by the company in the early 20th Century during the inter-war period which complements the ‘Shipbuilding in Hong Kong’ forum topic I posted in April 2020 about the company’s competitor The Taikoo Dockyard.

Other contributors have already explained how in the 1860’s the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P & O) Company’s Chairman, Thomas Sutherland and local representative Douglas Lapraik registered their Hongkong and Whampoa Dock Co. (1866) in which Jardine Matheson also took a substantial financial interest. What has not been covered in much detail is how this ‘new’ company’s assets initially consisted of an amalgamation of several small ship repairing ventures in the Whampoa district on the banks of the Pearl River, south of Canton and a couple of existing dockyards in Hong Kong .

The lucrative south China dockyard business had beginnings going back to pre-Opium War days when merchant vessels from Europe & America, which were allowed to anchor at Whampoa, required maintenance for their ships before the long sail back home. These services were provided by a number of Chinese boatbuilders who established slipways on the mudbanks of the Pearl River. They were located mainly on “Dane Island“ (Changzhou 长洲) opposite Whampoa where the foreign ships used to anchor, not being permitted to venture further up the Pearl River and closer to the city of Canton.

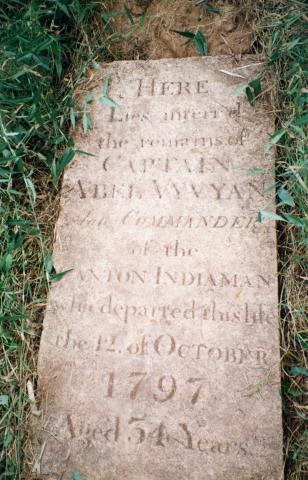

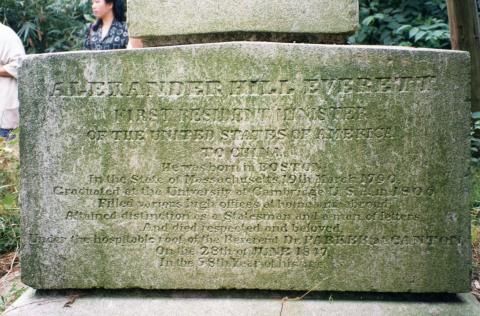

"Dane Island", as it was then called, is also immediately adjacent to “French Island" (Shenjing 深井 ) separated only by a very narrow channel . It is here that not a few foreign seamen stayed on permanently, although not intentionally. Succumbing to dysentery, typhus, cholera or malaria etc., their remains were interred on the slight incline above the muddy flats in what became the Whampoa “Foreigners Cemetery”. The gravestones remained undisturbed for many decades although many of the larger slabs were removed over time by villagers and used for other purposes such a stone tables or paving stones. A heritage restoration project by the Guangzhou government in the 1980's saw some of these stones retrieved and put back on the original site creating a tourist feature, although seldom visited these days because of its isolation. There is also a separate Parsee cemetery on Dane island.

Captain Abel Vyvyan who died on 12th October 1797. Vyvyan was Captain of the East India Company’s ship “Canton” which made several trips to China. Details of these trips and their captains’ names are listed on this Wikipedia site here .

The tomb stone reads " Sacred To The Memory of LT. EWD. Babington of H.M. ROYL REGT Who Departed This Life DEC 28. AD 1823 ". There is British War Office Record mention of a Lt. Edward Babington of the Royal Regiment of Foot on pages 156-157 on this site (Link)

Alexander Hill Everett ( 1792-1847) was the first resident American Minister to China. Having been appointed in 1845, he sailed for Canton but returned home before reaching there because of illness. In 1846 he sailed a second time eventually reaching Canton in the summer of 1847 but died shortly later on 28th June.

The directors of P & O shipping company, which during the 1840’s was heavily engaged in the opium trade, were in no mood to entrust their expensive ships to repair yards in China without European supervision. Enter one John Couper, initially a carpenter employed in P & O’s services. Couper was a very enterprising man who speedily realized the requirements of the modern shipping trade. He succeeded in leasing the land near Whampoa on which some crude mud bank slips already existed and set about constructing a granite-lined dock suitable for the larger modern vessels. Completed in 1845 , it was an immediate financial success.

With the continuing bickering between Chinese authorities and the foreign traders at Canton over the ‘illegal’ opium trade, hostilities inevitably broke out again in October 1856 with the “Arrow War” (a.k.a. “2nd. Opium War”), which was triggered by the seizure by Chinese marines of a small cargo sailing ship named “Arrow” for suspected piracy. The ship, a lorcha, was captained by Thomas Kennedy and flew the British flag although its registration had expired. The British responded in their usual fashion (sending gunboats) and pulverized the Chinese forts guarding the Pearl River. With the Chinese government being somewhat angered by this, poor Mr. Couper’s dock and facilities were destroyed with the stone lining being tossed into the water. Couper himself was kidnapped and his fate was never discovered. Following China’s defeat at the end of the Arrow war and conclusion of yet another “unequal” peace treaty, the Chinese government eventually awarded Couper’s son $120,000 compensation for his father’s loss. The dock was pumped out, repaired with the masonry re-laid and by 1861 the enterprise was up and running again.

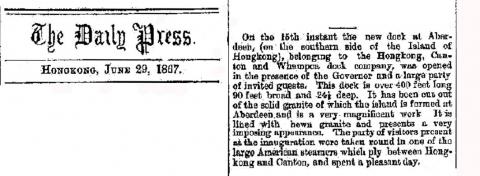

In 1863 P & O’s Sutherland and Laipraik created their new Hongkong & Whampoa Dock company, taking over Couper’s dock, and another nearby ‘Lockson Dock’ at Whampoa as well . Two years later they acquired John Lamont’s dock at Aberdeen on Hong Kong Island in addition to the adjacent “Hope” dock then under construction at the request of the British Navy for new larger dry docking facilities for their larger ships. The Hope dock was opened on 15th June 1867.

In 1870 the company further amalgamated with the Union Dock Company which had premises with two docks at Hung Hom, Kowloon. Mr David Gilles (Gillies Avenue in Hung Hom commemorates his name) became Secretary and General Manager of the growing company in 1875. Two years later Captain Sand’s patent slipways which had been erected at East Point, Causeway Bay were also purchased and moved over to the expanding Kowloon dockyard facility. In 1880 the Cosmopolitan Dock Company’s single dock and related facilities at Tai Kok Tsui were added to the HK & Whampoa Co.’s property portfolio, providing them with a virtual monopoly of dockyard facilities on the Kowloon peninsula.

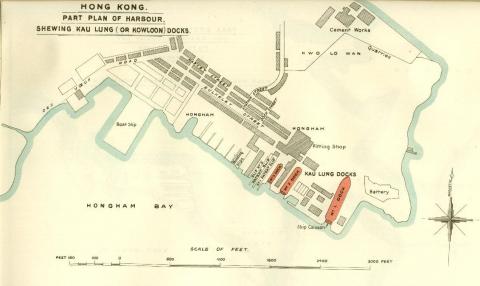

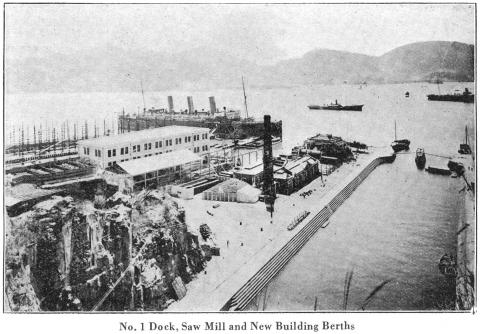

However, by the end of the 1870s, the British Admiralty were complaining that the Hope Dock at Aberdeen was proving insufficient in size as well as presenting berthing difficulties for deep-draughted ships during low tides. A decision was therefore made to build a new larger dock at the Hung Hom facility for which the British Government contributed £25,000 in return for priority of use for 20 years. This became the company’s “No.1 Dock”, initially 600 ft in length, being completed in 1888. (In the early 20th century this was extended in length to 700ft) The two earlier smaller docks were designated No.2 and No.3

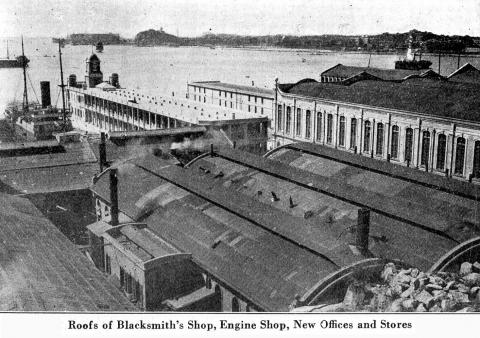

At the turn of the 20th Century the layout of their Hung Hom premises of the company was looking like this .

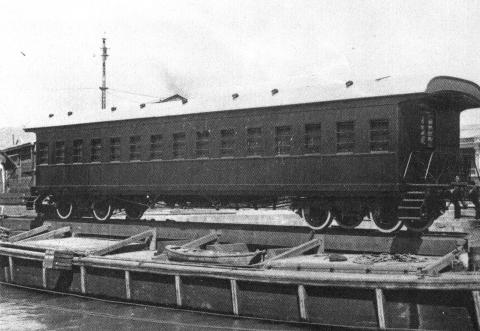

The company’s business continued to grow and prosper under Gillies’ management, and following his retirement in 1901, he was succeeded by Walter E. Dixon, William Wilson , Robert H.B. Mitchell respectively and then Robert. M Dyer (of Dyer Avenue) in about 1911. Dyer appears to have served as Chief Manager for some twenty years until 1930. During this period the company was not only repairing and building boats and quite large ships but also landed several contracts between 1910 and 1915 for constructing the wooden bodies of 24 passenger coaches for the Kowloon-Canton Railway. The wheels and the underframes having been supplied from the Metropolitan Amalgamated Railway Carriage & Wagon Company of Oldham, England.

This picture indicates that the coaches built at the Hung Hom dockyard were delivered on a floating barge fitted with a length of railway track mounted on a wooden trestle. This suggests that a connecting railway line from the KCR maintenance depot to the dockyards had not yet been built.

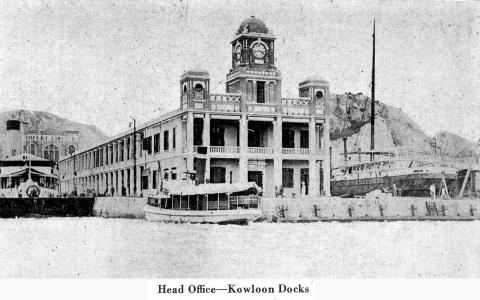

From the 1920’s the dock yard had considerable prominence on the Kowloon waterfront across from Causeway Bay with an impressive Headquarters building with a clocktower. This was located between the No. 2 and No. 3 Docks.

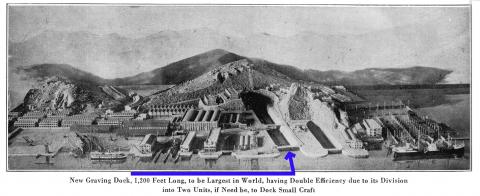

During the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley in 1924, the Hongkong and Whampoa Dock Co. together with its competitor, the Taikoo Dockyard , both exhibited a large model of their respective facilities. It was of great interest to the British public to see that Hong Kong & Whampoa Dockyard Co, now generally referred to by the public as just “Kowloon Docks”, was preparing to build and the world’s largest graving dock in the world at that time. This was to be 1,200 feet in length and “at least” 128 feet in breadth and large enough to take the biggest liners and most powerful battleships. The dock would also have a divider capable of separating the long dock into two shorter ones, taking ships of up to 710 ft. (inner section) and 470 ft (outer) respectively.

The then proposed new Graving Dock is shown in the model ( indicated by the blue arrow)

However, this was not to be. The British government had already decided to build a new Royal Navy base at Singapore, as Headquarters of the “China Station” ( later in 1941, this was renamed the “Far East Fleet”) . Although construction of the new Singapore facility at Sembawang got off to a slow start, the plans for Hongkong & Whampoa’s expansion plan fell victim to the worst recession Hong Kong had ever faced, triggered by a series of workers’ strikes and boycotts orchestrated from Canton. The economic malaise persisted for the remainder of the 1920s and into the 1930’s during which time Shanghai overtook Hong Kong by leaps and bounds as the most important Far Eastern international trading centre. The planned large dock never got built in Kowloon and instead this prize eventually went to the Royal Navy’s Singapore base with the construction of the King George VI Graving Dock. This was the world’s largest at that time, although not completed until 1938. It was captured by the Japanese only 4 years later and put to good use during the war after repairs had been carried out to make good damage done by the British in an attempt to destroy it before their surrender.

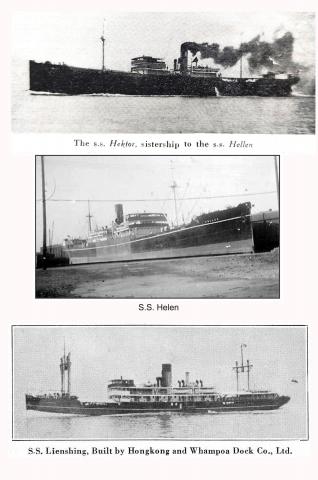

In spite of Hong Kong’s economic difficulties and problems with strikes during the twenties, Kowloon Docks still managed to complete some noteworthy shipbuilding contracts in the early 1920s before business declined rapidly in 1925 when the recession set in.

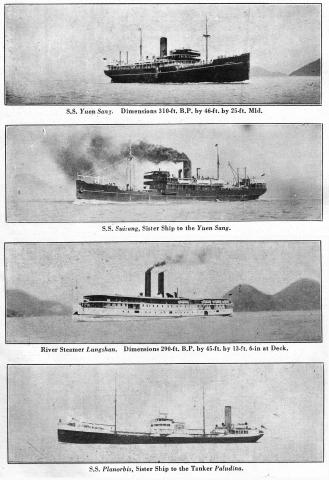

The three ships illustrated above are:

a) S.S. Hektor launched March 1921 .

b) S.S Hellen launched June 1921 .The Hellen was sunk by torpedo 22.12.1941.

c) S.S. Lienshing, launched 26 Mar 1924 for the Indo China Steam Navigation Co. It ran aground and was wrecked only two years later (12.12.1926) between Tientsin & Shanghai. There were 237 passengers aboard. All abandoned the ship in lifeboats but 40 Chinese passengers fell into the sea, many of whom, against orders, had returned to the wrecked ship thinking that it had settled on the rocks and would not sink further. They also thought it would be drier and more comfortable to await rescue and that they could save their luggage and belongings. The loss of life was 25 although only 8 bodies were recovered. In the later Maritime Court enquiry held in Shanghai, the British Second Officer was held responsible because he was in charge of navigation at the time and had negligently taken the wrong course. His First Officer’s certificate was suspended for 12 months although he was allowed to retain his lower 2nd Officer’s certificate. The ship was not salvaged, becoming a total loss.

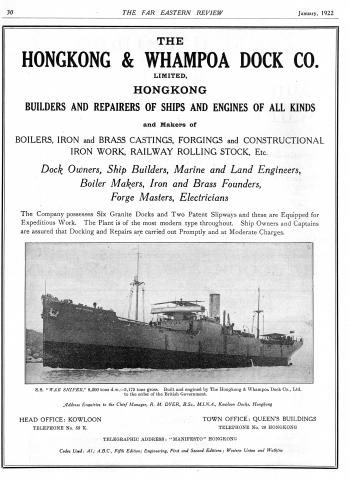

The War Sniper was one of four similar vessels built by the Hongkong & Whampoa Dock Co. The ship was sold to the Court Line almost immediately upon completion and renamed as 'Ilington Court' . The ship was sunk by a German torpedo on 26 August 1940.

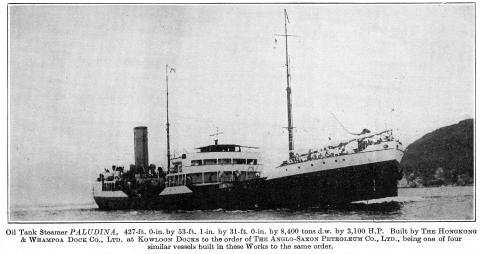

a) S.S Yuan Sang ( launched Dec 1923)

b) S.S Suisang ( launched Nov. 1923 - sister ship to above)

c) River Steamer Lungshan , launched in 1923 - month unknown

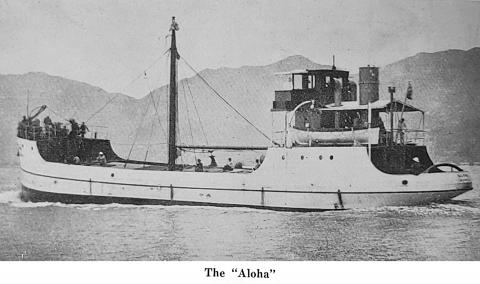

d) S. S. Planorbis launched Apr 1922 oil tanker .

22. S.S. Changte launched in September 1925 for Australia Oriental Line (AOL)

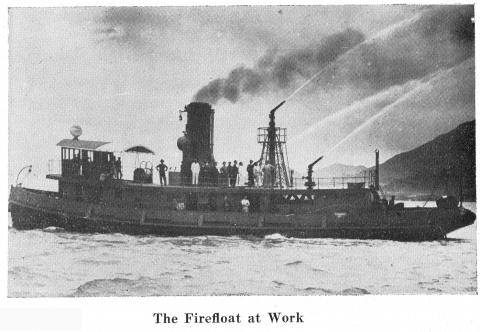

This fireboat (name unknown..... can anybody help ? ) was built by HK& Whampoa Dock Company to special designs drawn up by the Hong Kong Fire Department, then a sub-unit of the HK Police Force. It is seen here during the trials, soon after the boat's launch.

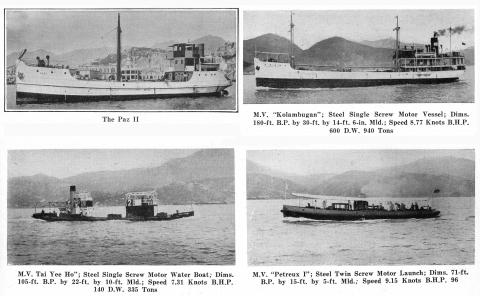

a) Paz II for Manila launched 1927

b) M.Vs Tai Yee

c) Kolambugan launched in 1929

d) Petreux

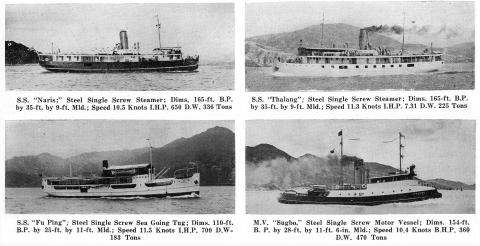

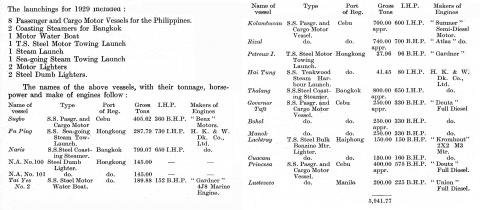

By 1929 there had been a slight recovery from labour instability and interference in trade with the company reporting that they had succeeded in launching sixteen vessels that year, although with the largest two vessels both being only 165 ft in length, these ships were well short of the No.1 Docks maximum capacity of 700 ft. The company for the first time in several years recorded a gross profit of about $650,000 but after deductions (which included directors’ fees) the net profit was a miserly $614.

a) S.S. Naris

b) S.S.Thalang

c) S.S. Fu Ping

d) M.V. Sugbo . ( all four launched in 1929 )

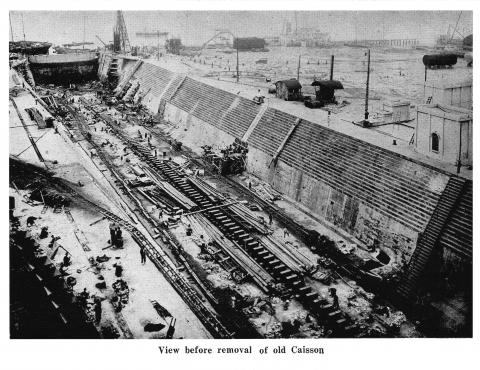

With prospects recovering in 1929 the directors revisited their earlier intention of building a new dock, which would take the largest ships then operating on the Pacific Ocean routes. However, the cost of an entirely new dock was considered too expensive so they opted instead to widen Dock No.1. The sides were cut away making the width at floor level 88 ft, providing an additional 18 ft over the previous dimensions. The contract for doing this work was awarded to Lam, Woo & Co. the builder who had recently built the European YMCA Building in Salisbury Road. ( Link : https://gwulo.com/atom/27270/zoom ) .

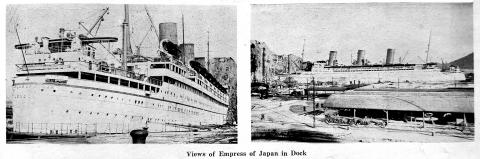

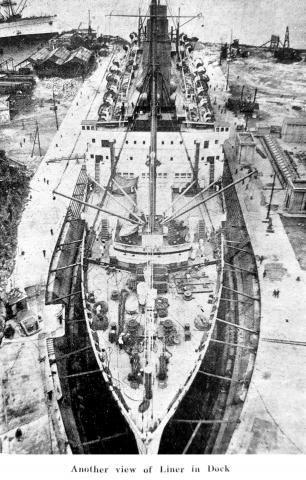

This picture shows the casson before removal during the dock-widening construction work in 1931. During the widening works it was still possible to make use of the dock and this fact was born out when the R.M.S “Empress of Japan” with a length of 673 ft and beam 84ft. entered the dock on 15th January 1931 for maintenance.

Photos of the 'Empress of Japan' in Dock.

The car ferry “ Kanlaon” was built by HK & Whampoa Dockyard in 1931 for inter-island services between Ililo and Pulupandan in the Philippines. Car Ferry “

During the 2nd World War the docks suffered very heavy damage from bombing. The Hong Kong Industrial History Group website has well-illustrated article about the damge caused here ( link HERE)

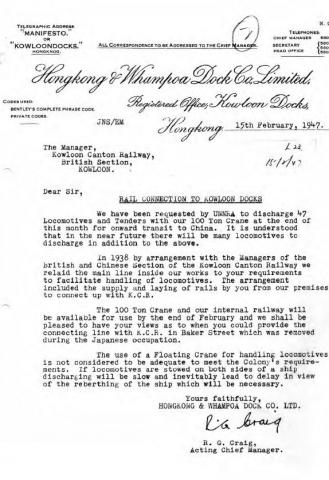

Prior to the war the Hung Hom dockyard had a railway line exiting from its own extensive internal network of tracks. This line ran down the alignment which was later named Baker Street, across Chatham Road, and then into the Kowloon Canton Railway’s maintenance depot. During the war this track was lifted by the Japanese. After the war, in February 1947 the dockyard’s Acting Chief Engineer wrote to the KCR requesting with some urgency that the connecting track be re-laid in expectation of the delivery and off-loading in Hong Kong of a large number of donated UNRRA steam locomotives for the rehabilitation of China’s railways.

Unfortunately, the General Manager of KCR replied that they were unable to help with this request because they had a severe shortage of steel rail tracks and associated equipment, having already borrowed some from China just to keep running. So in the following month when the engines arrived, other arrangements had to be adopted.

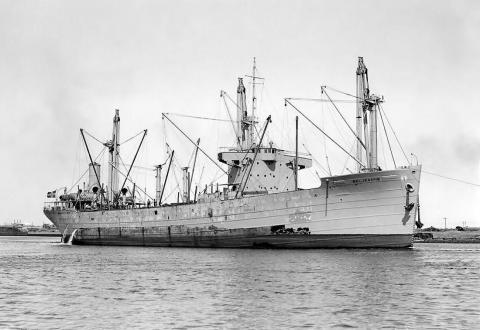

The Norwegian-Registered S. S. 'Beljeanne' was built in 1946 by Vickers-Armstrongs Ltd. of Newcastle upon Tyne. It had a special cargo hold and deck configuration for the shipping of large railway locomotives and rolling stoick. It was used extensively following the war for transporting railway locomotives, coaches, wagons, breakdown cranes and other surplus railway equipment There is a short Pathe film clip of the ship carrying railway carriages (Link) here .

The MV Beljeanne is seen above when it had arrived in Hong Kong on 30th. March 1947 with a consignment of 47 UNRRA locomotives for unloading at the KCR’s seafront railway siding. From here the locomotives were to be transferred by rail to Guangzhou, mainly for use on the Canton-Hankow Railway. The Hongkong & Shanghai Bank Building, towering above the surrounding buildings, is visible in the distance on the opposite side of the harbour.

When the locomotives arrived in Hong Kong, the Beljeanne according to press reports, berthed “a third of mile from the KCR sidings”, (at Holts Wharf) where they were hoisted from the ship by a floating crane, which in turn lowered the locomotives onto the KCR’s seafront railway siding, immediately south of Kowloon Station. This siding had been laid down hurriedly specially for this operation because KCR had ben unable to rebuild the line connecting with Hongkong & Whampoa Dockyard in time for the delivery.

For this operation the ex-Japanese Army's crane ship “Seishu Maru” was employed, by then in the services of the Royal Navy, having been seized at Singapore following the Japanese surrender. However even this unloading manoeuvre had been made complicated because the previous year (July 1946) a typhoon had swept through Hong Kong grounding half a dozen ships including Seishu Maru. The ship was later salvaged and patched up but its propellers had all been wrecked beyond ready repair.

This photo shows the crane ship “Seishu Maru” with a large U.N.R.R.A locomotive suspended from its giant crane. The scene is of the harbour with the crane ship approaching the railway siding on the seafront to the south of the platforms of the KCR’s Kowloon Terminus in Tsim Sha Tsui. The locomotive bears the number 1034 on the driving cab-side. This indicates that this locomotive was constructed by the ALCO locomotive works, one of 35 of this class of engine built by this company to the order of the U.S. War Department for use in China. Orders for 80 and 45 similar engines were placed with the Baldwin and Lima Locomotives works respectively, making a total of 160 locomotives of this type shipped to China in 1947-1948. Towing the crane ship is the tug boat “Poplar”, belonging to the Waterway Transport division (“CWT”) of the China Chinese National Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (CNRRA).

Another photo of the crane ship Seishu Maru offloading a UNRRA locomotive in Hong Kong , March 1947, when 47 similar locomotives were delivered to Hong Kong aboard the M.V Beljeanne for transfer to Guangzhou via the Kowloon Canton Railway. This engine is numbered 1004 indicating it was built by the Baldwin Locomotive Works. The crane ship, lacking its own propulsion, is under tow by an unseen tug. In the background are the warehouses of the Government’s Kowloon “Naval” Dockyard , which suggests that the locomotive transport ship Beljeaane was berthed alongside here or at the northern end of the adjacent Kowloon Wharves. Most of the locomotives were unloaded from the ship, while berthed nose-in at Holts Wharf, but apparently after a few days into the operation to unload the engines, the berth was needed for other consignments and ship had to move around the corner of Tsim Sha Tsui peninsula and be berthed at the northern end of Kowloon Wharf close to the Kowloon Naval Dockyard. Here, the last few engines were unloaded. (I am grateful to Stephen Davies for helping me identify the tugboat, reveal that the Seishu Maru had been salvaged after the 1946 typhoon (other maritime history websites claim the crane ship was a total loss in 1946) and also for helping me sort out the muddle of where the Beljeanne was actually berthed during its entire visit)

The crane ship Seishu Maru lowers an UNRRA 2-8-0 locomotive onto the track of the seafront railway siding alongside the Kowloon Canton Railway’s terminus at Tsim Sha Tsui. In the background is a Holts Wharf warehouse, still adorned with camouflage paint. The railway crossing on the Holts Wharf access road leading to Salisbury Road is also visible. This photo, from the UNRRA Archives, was incorrectly captioned as being a scene at Woosung (Wusong) near Shanghai. The archivists have mistakenly mixed this photo negative up with others depicting a later delivery of similar locomotives made to Shanghai in July 1947.

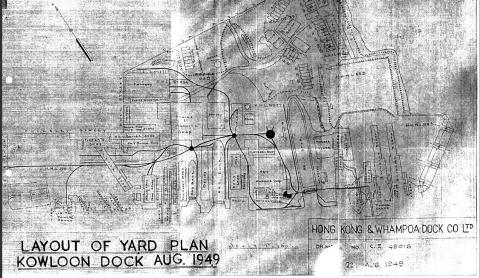

It is, as yet, unclear when the pre-war rail connection between the Hongkong & Whampoa Dockyard’s premises was re-established along Baker Street. Maps and plans from the period 1949-1960 do suggest the internal dockyard’s ‘light railway’ tracks reached the works entrance on Gillies Avenue and this is labelled “To KCR” on a dockyard plan dated 1965 . There is also a suggestion on a British military map that a grooved rail line ran across Chatham Road from the KCR maintenance depot but the continuation of this track down Baker Street is not illustrated.

Layout of Dock in 1949 showing the internal railway track extending though their premises and exiting the dockyard at the west exit onto Gillies Avenue.

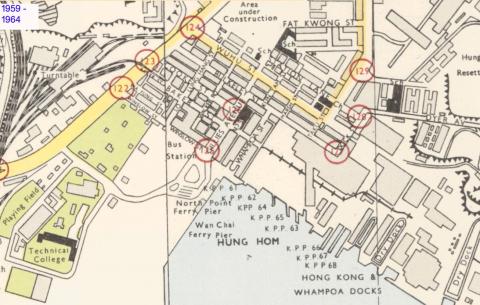

Extract of British Military map based upon surveys conducted by the Royal Engineers in 1959-64. The map indicates a light railway still running through the dockyard premises and exiting at Whampoa Street in alignment with Baker Street upon which the tracks formerly ran to connect with the KCR Depot. The connecting track from the KCR depot across Chatham Road is also illustrated.

Restoration of Baker St. rail link from Kowloon Docks to KCR

This new find and post by IDJ, anwers my query about when the KCR rail link was re-established. It was too late for the locomotive deliveries in 1947, confirming the reason why the crane ship had to be used. . ( Thanks IDJ)