Hong Kong’s criminal women

Primary tabs

With the recent publication of Women, Crime and the Courts: Hong Kong 1841-1941, I hoped author Patricia O’Sullivan would share some of the book’s themes and stories with us, and also tell us a bit about how the book came to be. Patricia kindly agreed, giving us Gwulo’s first newsletter for 2021:

How it all began …

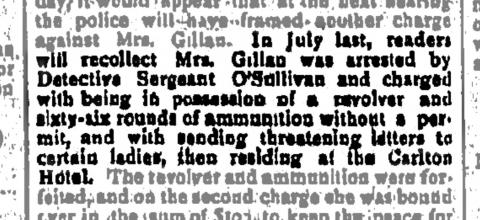

I suppose that it was the cantankerous Amy Gillan that started it all. Not one of the gory chopper murderers or callous kidnappers, but a disturbed Western woman bawling out ‘doctored’ hymns and shooting off obscene poison pen letters that became my Case No. 1.

I had been following the Hong Kong Police career of one of my grandfather’s cousins, Edmund O’Sullivan. In 1895, he had swapped the hard but not unrewarding life of a dairy farmer in rural Ireland for the uncertainties of the policeman’s lot ‘out East’. In his 19-year career as a detective, Edmund saw more than his share of excitement, including a political murder, the gory ‘Body in a Trunk’ case, and a tense high-stakes bank fraud. There was, perhaps, a sense that his investigation and arrest of this ‘neighbour-from-hell’ was in the way of light relief for him, even if she did possess an unlicensed loaded revolver.

One of the things that attracted me to this apparently trivial case is that the accounts gives a glimpse of the way that ordinary, working class European women lived. It had puzzled me how little I had been able to find of this in the available histories of Hong Kong. In the UK, by the 1970s and 80s, social history had become so mainstream that it was on school exam syllabi, and we learnt about conditions in 1850s woollen mills along with the foreign policy of the Louis XIV of France. But in Hong Kong, it would seem as if the problems of telling the story of this unique city, where ethnicities and cultures were both intertwined and yet rigorously divided, was so great that most could attempt to tell only a structural history. This is not to ignore the wonderful world of such as Carl Smith, Susanna Hoe and others, but such writers really are the beacon exceptions.

Women in the papers and the courts

The years I’d spent scouring old Hong Kong newspapers as I researched my previous book had given me the start of a collection of cases in which women, both Chinese and Western, stood before the magistrates. So I looked at these again, wondering if they would give a similar window into the lives of ordinary people? I suppose it was inevitable that I became as interested in the stories being told as what the inferences I could draw about the world of these long-gone people. Well, who can resist a good crime story? And would I find juicy murder along the way?

Although I was familiar with stories of the cities of Victorian England and Scotland, where between 25% and 37% of defendants at Magistrates’ courts and equivalent were women, I knew enough of Hong Kong not to expect this. Yet I started reading the Police Intelligence columns of the 19th century papers wondering how I could identify male and female names amongst those reported, only to realise that so rare was the latter, that her gender was always noted by the writer. This was confirmed by the crime and prison statistics produced by the Administration and sent to London in the annual Blue Books. Just 5% or so of those on the charge sheets that century were women, and the proportion did not increase to any great degree in the period before the Japanese occupation of the colony in 1941.

It was, generally, only the magistrate who adjudicated on women’s fate in the Hong Kong courts. The total numbers of defendants sent to the Criminal Sessions was never high, especially in the nineteenth century, and here a woman’s appearance was a rear rarity. Not surprisingly, therefore, most of the ‘cases’ I had were merely one or two lines: reporting the possession of non-government opium and a fine of one dollar, or an arrest for hawking without a licence, ‘illegal possession’ of a few lumps of coal or tying up a sampan in a restricted part of the harbour. In amongst these petty infractions, though, were crimes that called out for sanctions beyond a few days in gaol or a paltry fine. And of those with female defendants, not a few brought the colonial criminal justice system into collision with centuries-old customs and social structures.

Kidnapping, a profitable trade

These practices prescribed that the relationship between people overruled individual autonomy, whether that was between father/son; mistress/mui tsai; master/servant. But as with customary behaviour world-wide, the checks upon them supplied by the culture around were often lost when transported to a slightly different situation. Thus those who wanted to profit from the power they could wield over others saw nothing wrong in abducting a child from her parents and selling her, though intermediaries, into prostitution or servitude in Singapore, California, Straits Settlements or Hong Kong. Such kidnapping and trading of children (boys and girls) and young women was a common occurrence. And when the object was female, women were frequently closely involved. Indeed, for them it was an opportunity to make sums of money unavailable otherwise. It seems probable that only a small proportion of such abductions came to the attention of the law, and when they did, the trail of evidence was often obscure. But such cases at least resulted in the liberation of the captive child or woman. A brief report in the Daily Press for 14th August 1875 is typical of this and the limited success of such an arrest.

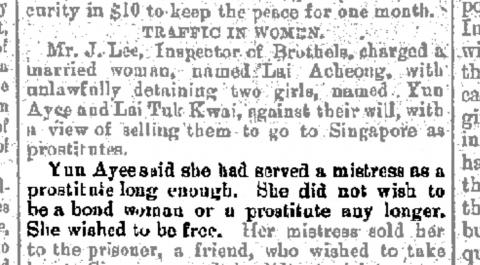

Yun Ayee’s dream of freedom

Untangling the somewhat confused story, it appears that Police Inspector John Lee, attached to the Lock Hospital as Inspector for Brothels, had been ‘tipped off’. His informant told him that a married woman, Lai Acheong, had returned to the colony – perhaps from Macao or Canton, with two young women, apparently still in their teens, and they were now in her house. Perhaps neighbours also told him that the girls seemed to be making some disturbance. He spoke at length to both young women and one, Yun Ayee, found the courage to tell the policeman her story. She had worked (outside Hong Kong) as a prostitute for four years, although she had previously lived in the colony since she was nine years old. Now she had enough of that life and wanted to be a free woman. She thought she had certainly served her time to her mistress. But then the mistress had sold her to a friend, Lai Acheong, who, with another woman, Mah Achee, had been visiting. These two women had taken her and the other girl back to Hong Kong with them.

When they arrived in Lai’s house they had wanted to go out, but were forbidden. In fact, they were not even allowed to look out of the window. A few days earlier, their kidnappers told them they would send them both to Singapore. The women did not say what for, but the girls could guess. Yun repeated to Insp. Lee that she wanted to be free, but how could she, now that this woman had paid her former mistress for her? She had no way of getting hold of money to pay off the bond! She was vastly surprised, therefore, when the inspector told her that in Hong Kong she could be a free woman without any payment being made. He would arrest Lai Acheong and perhaps the other woman, and after that, they would both be free.

After listening to the girls, the policeman acted quickly, before any attempt could be made to smuggle the girls onto a Singapore-bound vessel. He arrested only Lai Acheong, but later that day all four women appeared at the magistrate’s court. However, after Insp. Lee’s statement was made, the newspaper records that there was “a deal of conflicting evidence,” and the case was remanded to the next morning. At that hearing, magistrate Charles May could only bind the woman over for security of $50, to be of good behaviour for three months.

Yet at least the two young women were now free, and Lai Acheong could not force them to work for her. But free for what? How now would they make their way in Hong Kong, which offered limited employment opportunities for young, probably uneducated, Chinese women? Would they find any job other than that which they had tried to leave?

Some stories had better endings, as with another case ten years later when a 16-year-old girl from Canton had been abducted by a gang of men and then sold to a mistress who also planned to sell her to a brothel keeper in Singapore. Her employer, a chemist, regarded her more like a daughter than a servant, and made strenuous efforts to find her. Finally, after the girl had been captive for six distressing weeks, he was successful and they were reunited.

Desperate times, desperate acts

I was still on the trail of that big ‘scoop’, though. My experience of searching through the old newspapers has been that once you get one story, it tends to lead to other, earlier but related tales. So it seemed like a ‘good omen’ when the first murder case I found with a female protagonist was right at the end of my period, just 18 months before the Japanese invasion. Once investigated, it did indeed lead me backward, to other similar events. In the end I found (or had pointed out to me) ten cases of murder or manslaughter with a woman as a principle defendant. But as I read their stories and unravelled what I could about their situation and motives, there seemed nothing ‘good’ about that omen at all. Poverty and/or desperation were clearly the main factors in half of these, whilst others showed evidence of both confused circumstances and muddled thinking, with subsequent trials often failing to provide any real clarity. But back to that first case …

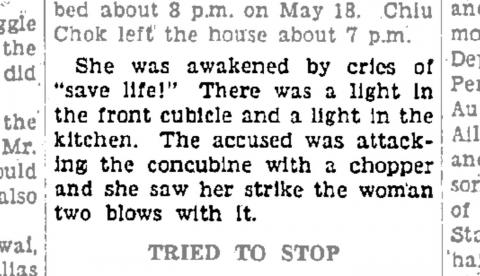

“Late one warm Sunday evening in May 1940, Kan Wai, watchman in Hee Wong Terrace, West Point, was doing his rounds. Known to all as Uncle Wai, he was a friendly and helpful man, who prided himself on knowing his area and its occupants well and being able to sort out troubles before they escalated into anything nasty. The road was quiet and dark, street lighting being rudimentary here, so when the door of No. 33 burst open and young Wong Miu-lin, old Chui’s daughter-in-law rushed out screaming, he was momentarily taken off guard. “She’s got the chopper, oh, Uncle Wai, she’s murdering us!” Uncle Wai knew that the women in the second-floor flat were quarrelsome - the shrieks between the Chui Chuk’s wife and concubine could often be heard down at street level, but this sounded bad.

Blood, everywhere

“Alarmed, Uncle Wai made for the apartment. Half way up the second flight of stairs he found Lam Lin-kwai, Chui’s concubine, slumped on the stairs. She was dressed only in her underwear, but that was soaked in blood. Stooping to see what he might do for her, he thought of the children in the flat. A sound made him glance up, and he saw Chui’s wife, Kwan Lai-chun, leaning against the door frame, holding what, in the dim light of the stairwell, looked like a chopper. Leaving Lam for the moment, he carried on up and spoke calmly to Kwan. “What are you doing with that? Come on, give it to me. You don’t have to make a family matter so serious. Let me have that.” He took the chopper from the woman. It was covered in blood and seemed to have hairs and flesh attached to it.

“The amount of blood around alarmed him: Kwan seemed to be bleeding, she was certainly covered in blood, and there was more on the floor. Cautiously, he stepped further into the flat. In the passage near the door, Chui’s 85-year-old mother was lying in a crumpled heap on the floor – she wasn’t moving or making any sound at all. One hand appeared to be completely severed at the wrist. Then he glanced across at the other cubicles – where were the children? Didn’t Lam have a couple of kids? Checking to see that Kwan was still at the door – and the chopper was on the stool, where he had put it, he made his way further in. The first cubicle he tried was locked, the next empty, but as he made for the front one, he passed another bed-space in the passage. He had to hold the door frame opposite for support for a moment – the bed containing the two little bodies was a mass of blood …”

Initially I was puzzled by the questions that hung over this case, yet I was to find that, compared to other such murder cases, this was almost an indisputable case. Almost. That said, it is another aspect of the story that resonates through so many of the accounts of women on the wrong side of the colonial law in the pre-1941 period. In essence, Kwan Lai-chun’s defence, when charged with the murder of Lam Lin-kwai, had been the child’s wail of “she hit me first”. It wasn’t, as she expressed it, even really a matter of self defence. She seemed unaware of the possible consequence of her actions. In other cases, the women involved come across as having little idea of the difference between a story and an account - the latter being quiet foreign to them. Few of the Chinese women portrayed (and some earlier Westerners) had received any education outside the home. This confusion could have serious consequences, as when the younger defendant in the sensational Au Tau killing of ten years earlier almost talked herself into a murder conviction.

The door of the gaol clangs shut …

Of course, having unearthed the crimes and prosecutions that resulted in prison sentences for these women, I couldn’t leave them as they were escorted from the court. What provision was made for their incarceration? Robert Peel’s reforming Gaol Act was already 20 years old at the outset of Hong Kong’s colonial existence. The scandalous treatment of women in English prisons before that Act was something Victorian Britain was keen to forget. Obviously, here in Hong Kong there would be separate accommodation for convict women, well away from the male cells. But where and what, exactly? The books then available were almost silent on the subject until the post-war period. (The recent publication of Crime, Justice and Punishment in Colonial Hong Kong by May Holdsworth and Christopher Munn, gives a much richer history of Victoria Gaol.)

Accommodation for female prisoners was almost always, it turns out, rather an after-thought. The very first women to serve a sentence were held in a room in the house of the Magistrate. After that, and until the building of Lai Chi Kok Women’s Prison in the 1930s, space had to be found where it could. When the ‘new’ prison of 1862 was built, the eastern-most end of the ground-floor wing, close to Arbuthnot Road, was designated at the ‘Women’s Prison’. But even that to be given up when, in 1885, overcrowding in the men’s prison and prison hospital reached crisis point. Security was never an issue with the female prisoners - Superintendents often remarked on how well-behaved the women were, so a vacant house in Wyndham Street was rented for them and a modest amount spent converting it into a rudimentary prison.

Wyndham Street - an unconventional prison

Fortunately, that year there was then only an average of six prisoners being held on any day, so it was a simple matter to take them the short walk down Arbuthnot Road to the house. The rateable value of the building suggests that this was not large. However, numbers in this prison were growing, and it, too, would soon be overcrowded. Indeed, for example, during most of 1892 there were usually around 27 women held there, either waiting on remand or serving their sentences.

The Matron was supposed to segregate her charges, according to the type of prisoner (remand, debtor, long-sentence etc., and by race), but this must have been well-nigh impossible in a small house, with only a couple of individual cells, and with only this one woman in charge. But by 1891 the government was having to take notice of the problems the Gaol encountered in recruiting its staff because of the wretched pay and conditions it offered. Wages were increased for all the Westerners and for the more senior Chinese posts. The Matron’s salary rose from $25 to $40 per month - less than half that of a man in a post of similar responsibility. But equally welcome was the news that she would henceforth have a ‘Nurse’ to assist her - although finding suitable women for the very low-paying job was, predictably, difficult.

The Wyndham Street house had apparently no kitchen, as meals had to be brought by prison coolies from the gaol kitchens. But it did boast bathing and clothes washing facilities. The area had buried drains, but of limited size, so the house would have utilised the night soil collection system that was standard in the colony, rather than flushing water closets. A pressing concern was that the women only had the enclosed side yard of the building in which to exercise. A space of 24’ by 9’ could only hold a few at a time, if they were to be properly supervised and prevented from talking to one another. Although so close to the main building, it was isolated, for it would be many years before the gaol had an internal telephone system. An obstreperous or even violent prisoner might cause real problems for the matron, yet there are no reports of any such incidents.

The women of Wyndham Street

So, in 1892 it was an almost daily occurrence that the Matron had to receive yet another woman, perhaps one who had received the relatively stiff sentence of six months for possession of unlawful opium, but more likely the hawkers and petty thieves who would be with her for just a few days. Each, though, had to be searched, bathed and clothed in prison uniform. The rules had to be explained to her, a bed space found and food provided. Those starting a sentence, rather than just being held on remand, had to be set to work, whether the ordinary labour of cleaning and sewing, or the hard labour of oakum picking or laundry work. Some would come with their babies, others might be heavily pregnant. The elderly were often near-destitute, and the prison offered more shelter than they could usually find outside. And then there was the woman who had attempted to end it all by throwing herself off the Praya wall. She had been hauled out uninjured, by an alert constable. She would not be punished, but attempting suicide was still an offence and she must appear before the magistrate who would decide what was best for her. So the police took her to the house in Wyndham Street, where the Matron had to get her dried out, ready to go appear in court the next morning. The hours were long, continuous really, and the conditions rough, but by the end of the nineteenth century the Matron of Victoria Gaol rarely had time to be bored!

Thanks to Patricia for sharing these extracts from her latest book, Women, Crime and the Courts: Hong Kong 1841-1941, which was published just before Christmas by Blacksmith Books. Copies of this, and of Patricia’s first book, Policing Hong Kong – An Irish History, are available to order from Gwulo.com. Local and international orders are welcome, with free shipping for all local orders:

For more insights into Patricia’s work, please visit her website, Hong Kong social history.

For more books about Hong Kong's history, please visit Gwulo's bookstore.

And if you fancy making your own discoveries, you can follow Patricia’s approach and browse through the extensive collection of old Hong Kong newspapers that is available to view online at MMIS, part of the Hong Kong Public Library's website.

Comments

Vitoria Goal

Thank you for your well-researched article and I have a special reason to enjoy reading it with great interest and nostalgia - being one young boy growing up in Arbuthnot Road 60 years ago where my bedroom window looked directly across to that southeastern corner of Victoria Goal, then as Justice's Clerk, Crown Counsel, Barrister in private practice (and almost full retirement after 42 years at the Bar); your article gives me so such joy and enlightenment in a nostalgic memory journey back to my childhood and career through life.

I say again Thank you.