At 4.15 p.m. Admiral Turner declares Saipan secured. The Allies are now about 1300 miles from the main Japanese islands.

One Japanese admiral said, ‘Our war was lost with the loss of Saipan’. Most of the Japanese garrison of 30,000 are killed and at least 1,000 civilians commit suicide to avoid capture.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Saipan#Battle

Bird’s Eye View: News in 1944

News from a foreign country came,

As if my treasures and my joys lay there…

Thomas Traherne

As Camp Secretary John Stericker put it:

News was meat and drink to us. Whether true or false, as long as it was good, we lapped it up.

1944 was a grim year for the Stanleyites: wheat bread and meat disappeared in February, and the only serious protein was provided by an ounce or two of low-quality fish every day. As the winter set in, there was a crisis over water supplies, which was unexpectedly resolved by the digging of wells, but thereafter both water and power provision was intermittent. All of this was the result of American bombing and submarine warfare, so, ironically, the worse the conditions in Stanley became, the more its inhabitants could be sure the Japanese were losing the war. They were naturally desperate to find out how quickly liberation might come. In fact, given the prevailing conditions, the question was whether or not this would arrive before the internees began to die off in large numbers.

After the arrest of some of the wireless technicians in summer 1943, to the best of my knowledge no attempt was made to contact the outside world through radio. This left the internees reliant on the Japanese-produced Hong Kong News for details of the war. This generally presented the conflict in the Pacific in terms of Japanese successes, but the internees soon learnt to read between the lines: if American planes were being destroyed closer to Japan in February than they’d been in January, then the bloody ‘island-hopping’ through the Pacific towards the main Japanese islands was progressing, and Stanley was that much nearer liberation.

But in the summer of 1944 a fresh source of news was allowed into camp and for about a year improved the internees’ understanding of the development of the conflict: Chinese newspapers. At some point – I don’t yet know when – a third source was made available. On August 27, 1944, George Gerrard writes:

Actually the Chinese and Japanese papers give us more up to date news than the English rag which is now only one page and double in price.

This suggests that as well as The Hong Kong News (the ‘English rag’) and the Chinese papers the internees could also draw on translations of Japanese language papers. A ‘case study’ of R. E. Jones’s comments on the important battle of Saipan will show that now they had three perspectives on the war they were, in many cases, able to get things almost right. But first I’ll describe briefly the ‘history’ of the Chinese papers in Stanley.

In his weekly retrospective for June 25, 1944 George Gerrard notes that Chinese newspapers are now allowed into camp ‘and they give a lot more startling news than the Hong Kong News gives’. R. E. Jones first mention of these papers is on June 15, 1944. On June 26 he notes that a Chinese paper has arrived and is being translated. He mentions the paper occasionally until February 8, 1945. On February 20, 1945 he notes that neither the Japanese nor Chinese papers were turned over to the internees. He sees the edition of May 1, but on May 18 records both the Chinese and Japanese papers are ‘stopped’ – and there are indeed no further references.

George Gerrard’s diary gives us a similar picture, and tells us more about the effect the generally cheerful war news of 1944 had on internee morale. He notes the fall of Saipan on June 25 – the same entry in which he first mentions the Chinese papers. In the July 9 retrospective he notes the effects on morale of the summer’s accumulation of good news:

Our invasion in France, the Russian’s terrific advancements…and Nimitz’s smashing up of the Japs at the Mariannas is really wonderful and we are all very bucked and eagerly waiting like Oliver Twist for more and more news.

On July 30, 1944 he writes:

The news continues to be good and our prospects are bright, both in the west and out east. Rumours of course are continuing to be wild but what we receive in the newspaper is good and then we are allowed to receive a Chinese paper which when translated gives us much more information as to what is going on.

There are no mentions after this until August 16, 1945, when the Japanese had surrendered, and Chinese newspapers found their way into Stanley. Gerrard’s ‘weekly’ format for keeping his diary means that he’s much less likely to report the ever-changing news and rumours. My sense is that in this respect (although not necessarily in others of course), Jones gets us closer to a feeling of daily life in the camp.

Jones refers specifically to events on Saipan in his entries for June 19/25/27/28/30/ and July 5/6/7/8/13/19/20. For example, on June 24 he mentions a naval battle to the west of the Marianas– this is presumably the Battle of the Philippine Sea, which took place June 19-20, and more or less decided the outcome of the struggle for Saipan. He’s frustrated at the delay in getting the news into camp:

Japs bombed Aslito airfield on Saipan 25th. All this news is three days old before we get it. Lots can happen in three days.

My guess is that the bombing (of which I can find no trace in online accounts, although that of course doesn’t mean it didn’t happen) was reported in the Chinese and/or Japanese paper and that it took two or three days to get this translated, but it might be the case that the Hong Kong News wasn’t being delivered speedily into camp. In any case, the point to note is that this airfield was important in the struggle for the island, so even if Jones is reading Japanese propaganda he’s learning something from it.

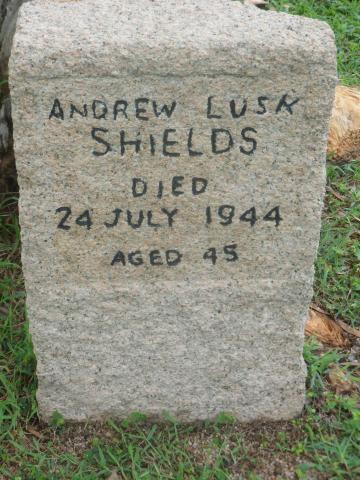

On July 7 he claims Saipan had surrendered on June 30 and notes it’s not mentioned in that day’s paper (either the Japanese one translated or, more plausibly, the Hong Kong News), whereas on July 19 he reports that Saipan was ‘ours’ on the 16th. I don’t think Saipan ever officially surrendered so Admiral Turner’s announcement today is the best indicator of the end of the battle. Jones’s two estimates are about a week wrong in opposite directions, but that’s not bad going under the circumstances.

In general his information is good. On July 5 he reports that the Japanese are fighting strongly on Saipan and elsewhere, and this was true: on July 6 they broke though American lines with an incredible charge in which anyone fit enough to walk joined in (those who couldn’t walk were shot and several officers committed suicide). On July 8th he notes that US officers implied the Japanese fought strongly and bravely, which was certainly correct, and that the bloody battle cost the Americans 10,000 casualties (Wikipedia gives about 3,000 dead and about 10,500 wounded). ‘Casualties’ is ambiguous: if Jones meant the total of dead and wounded he’s not far out, but he might have been recording an exaggerated Japanese claim as to the number of American dead. On July 13 he tells us that the ‘Jap paper’ reports there’s still resistance on Saipan, but on the 20th he notes that Japanese premier Tojo has confirmed the loss of the island.

What’s striking is how much better Jones’s reports are than earlier in the war. In the spring of 1942 he’d recorded that the Russians were in Warsaw (which they didn’t capture until September 1944) and wondered if the Malayan battles were ‘progressing in our favour?’ (as far as I can make out there weren’t any battles then as the Allies had long since capitulated). A little later he claimed

…33% Jap Navy & 60% convoys lost…

…a figure he seems to have believed emanated from President Roosevelt himself.

By 1944 the internees were getting much more accurate news of the war: they knew about D-Day, for example, two days after it had happened (see Jones’ entry for June 8, 1944). This is not to say there weren’t false rumours and exaggerated hopes: on November 14 and 18, for example Jones reports persistent rumours about Germany’s capitulation. But it seems as if the speculation was now based on a reasonably solid stratum of fact. And, ironically given the tendency in the early stages of the war to believe almost any optimistic rumour, when tidings of final victory come, there will be those who refuse to believe it!