A lady's impressions of Hong Kong

Primary tabs

This speech was gven to the Manchester Geographical Society at Finchwood, Marple, on Saturday, June 30th, 1900, at 6 p.m.

A LADY'S IMPRESSIONS OF HONG-KONG.

By MRS. UNSWORTH.

There has been within the last twenty years a growing interest taken in our own colonies. It may be that travelling has become so much cheaper and better, that we see more of one another. Formerly a person-going out to Australia or the East seemed lost to his friends and relatives for the rest of his life, only a small percentage returning. Now it is quite customary to visit friends and relatives living in the colonies, a journey to or from the antipodes being a very ordinary affair, and undertaken by some persons and families every few years. And then for those who do not visit the colonies, but who read of them, we know that the writings of Rudyard Kipling and others have done much to stimulate a sympathy and feeling of brotherhood among all races living under the British flag.

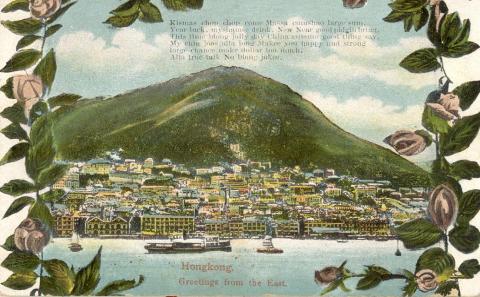

If we look at a map of the world, the British colonies being marked in some vivid colour, Hong-Kong looks small and insignificant compared to the large areas of Australia, Canada, or the possessions in Africa; but its importance is not to be estimated by its size alone. It is the position which makes it so valuable—first as a naval station, and secondly as a distributing centre for trade. It is marvellous in how short a time it has grown to its present importance.

Sixty years ago it was a "barren, rugged island," rising steep out of the water. At the water's edge were a few fishing villages, the resort of pirates. In those days no ships anchored there, but went to Canton, about eighty miles up the Pearl River, or stopped at a Portuguese settlement called Macao, some forty miles from the island of Hong-Kong.

But Macao was not all that could be desired for loading and unloading vessels; and Canton was worse, because of the many restrictions put on ships entering that port by the mandarins and governors of that province. Indeed, so impossible did they make it for British vessels to do any trade, by their fines and heavy duties, that the trouble culminated in bombardment, and after the second bombardment the island of Hong-Kong was granted to the British.

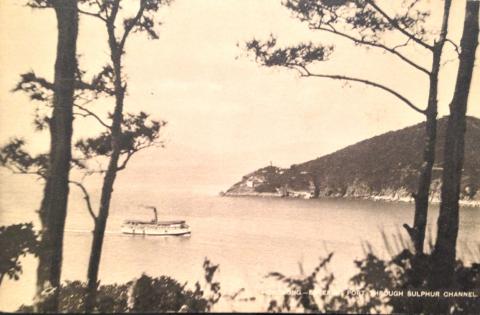

Then began the building of the city of Victoria, which has grown rapidly into a rich colony. The harbour is naturally a very fine one, being surrounded by high land, and entered by two narrow passes, one from the east and one from the west.

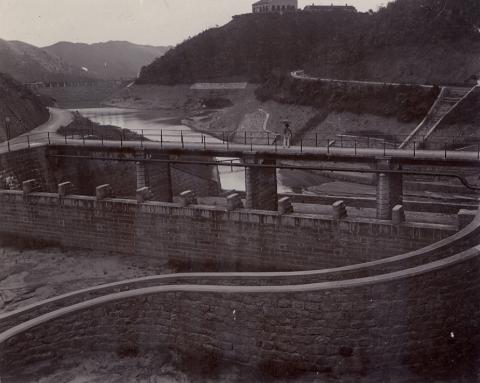

Large tracts of land have been reclaimed from the sea, on which level roads have been made, which were impossible at first, as there was no flat ground. Huge reservoirs have been formed among the hills for water supplies, road and waterways, built in such a manner as if they were to last forever, to resist the tropical storms.

Fine buildings, and gardens of tropical luxuriance, arranged in terraces, make it a fascinating city, set in the midst of a stormy sea. Also, by a judicious selection of the right trees for planting, the island is becoming healthier. At one time it was named the "Graveyard of the East," but that name has lost its meaning now, as the fever and miasma are receding before scientific remedies.

Any one visiting Hong-Kong would be wise to choose the months of November and December, as then the first impressions of this interesting island would be very delightful. Here there are bright blue skies, gay sunshine, and a fine, clear atmosphere, in which distant objects look marvellously near and beautiful. The ships coming in wend their way amongst the many islands and through a narrow pass, into what almost looks like a land-locked harbour. A bright panorama unfolds itself, the city rising out of the sea, with its terraces of houses and gardens.

Leaving the ship, to go on shore, anyone can go in a steam launch if they wish; but, in order to see the different phases of life, it would be better to go in a native boat called a sampan. The proprietor of this boat (the largest of which are from 24 to 30 feet long, and small ones about 12 to 15 feet) is a Chinaman, who owns no other house or home than this frail barque, in which he shelters his wife and numerous family, sometimes father and mother besides, in all three generations. They hold their family gatherings, their parties and festivities in it, and keep poultry. Just before China's New Year the company of a goose kept in an orange-box makes it a little livelier for the other emaciated cocks and hens.

These boats attend the ships to pick up passengers and carry luggage, earning a few pence for the trip. A space with a seat and a cover over it is set apart for the passengers, whilst the family ply the oars; the old grandmother, generally steering, nursing a baby, which is strapped to her back, and cooking at the same time.

On landing at the wharf one sees how large the Chinese population is. There are always crowds of coolies waiting about the streets and jetties; some with chairs on poles, almost like the old sedan chairs, to carry passengers up the hills; some with jinrickshas for hire along the level roads. There are no horse conveyances of any kind; this strikes one as very strange, coming straight from Europe. The great amount of traffic, the rushing about from the wharves to the warehouses, the loading and unloading of ships, and everything is done by human creatures. A horse in Hong-Kong costs more than many coolies, manual labour being very cheap.

The streets in the European part of the city have a fine appearance; the buildings are of granite, and they are built with arcades, under which pedestrians walk to keep out of the glare of the sun. But the European part is smaller than the Chinese part, the Chinese population being so numerous. Being a British colony, the Chinese are not allowed to build such narrow streets or crowd together so much as they love to do in their own cities. They are compelled by Government to observe some rules of sanitation; but they try to evade these as much as they can, and make, their streets as narrow as they possibly dare, and crowd them up with massive signboards hanging down, lines of clothing, and other obstacles. One can step out of Queen's Road, the central avenue where all the fine shops are, into a dirty narrow street where the poorer Chinese are living in a dirty, miserable condition and keeping up all their own unsavoury habits and customs.

The crowds in the streets are of all nationalities; of course the Chinese predominating. On first impressions, the lower classes seem to have no difference of sex; men and women look the same; and one person is the exact resemblance of another. But by and by you find out the men wear the long pigtail, whilst the women have a little knot of hair behind; and also, on closer observation, they begin to assume different features and expressions, some faces more attractive and some more repellent than others.

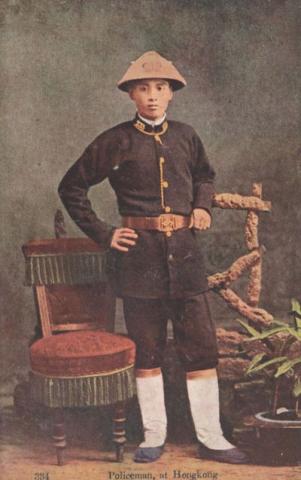

A Chinaman dearly loves a crowd, and to jostle and push, and there being so many of them, it would be impossible to get through some parts of the city if it were not for the policemen; some of these are Chinamen, some British; but the latter are mostly on duty at night time, whilst during the day the streets are kept in order by the Sikhs, very picturesque looking individuals, with their coloured turbans and white uniforms, fine long men, six feet high and more these put the fear of men into the Chinese and keep the streets passable.

There are other national elements in Hong-Kong besides Europeans and Chinese. There is a large community of the Macao Portuguese, and there is also a Parsee community. With all these different nationalities the streets present a very interesting spectacle. Before you can scrutinise one type some other steps in front of you. You may be studying a Corean, when a Hindoo will come and obstruct the view. Then whilst you are looking at a Japanese man or woman a Malay will bob up before your eyes. What with the native Indian soldiers, the British soldiers (sometimes a Scotch regiment in kilts), and the naval uniforms, the bluejackets, the marines, the sailors from every country, it becomes too bewildering, and presents a perfect kaleidoscope for colours and races.

The result of having a distinct and separate labouring class like the Chinese coolies, and labour being so cheap, is, that manual labour, except of a very agreeable kind, is despised and the tendency is that Europeans become rather luxurious and lead easy lives, as it is usual to keep many servants.

The European houses are built with large lofty rooms, and wide stone verandahs round the house, and some with gardens and tennis courts. But as the ground is limited and valuable, and as the houses cover more space than they do here, it makes the rents very high, in most cases absorbing a third or fourth of one's income. The servants' quarters, kitchens, and cooking offices are built a little distance from the houses. This is usually the case where servants are of a different nationality from the masters and mistresses. All the servants are men, except the nurses; no China woman will go out as a cook or a housemaid, all that is left to the men.

One might think that under these circumstances housekeeping was a very complicated business; on the contrary, it is very easy. If you hire a cook, he takes all the responsibility of providing, does all the shopping, thinks of everything needed, and soon adapts himself to your tastes and your income. Of course, he makes his own little commission; but it is very little, and is an understood thing. He will cook and do all this for the alarming wages of 28s. per month, or seven shillings per week, some more, and some less; besides, these are board wages, as he keeps himself in food. Then the house boy—who, by the way, may be fifty years of age; once a boy always a boy—takes all responsibility away from you of cleaning and looking after the house. He gets a coolie under him to do the scrubbing and washing of floors and windows (because a boy considers himself above scrubbing and cleaning), but he looks after all the rooms and the table, waits on and keeps them in order. Like the cook, he finds his own food, and all for the sum of 5s. per week; and the coolie, who does the scrubbing and cleaning, fetching, and carrying, enjoys the magnificent sum of 4s. per week, on which he feeds and clothes himself and keeps his wife and family. Hong-Kong may be described as a paradise for housekeepers, as far as regards an easy time and freedom from care, as the Chinese servants have adapted themselves to the business so well. A good house boy is a perfect treasure; he stops for years, indeed all his life, in a family that he likes, studies all your wants, takes care of all your property in the shape of clothes, furniture, etc., and his only dissipation will be a day or two off at China's New Year , in which to visit his friends, and about three days some part of the year to visit his ancestors' graves, and also his wife and family; even then he takes care to provide a substitute.

The intercourse between masters, mistresses, and servants is carried on through the medium of pidgin English; this is a kind of easy baby language that was introduced to trade with before the Chinese learned proper English. For instance, if you wish to intimate to your cook that you are having company to dinner, you say to him: "You catchee number one dinner; have got four or five picee man come." Or, if a mistress wanted to tell her boy he talked back to her too much, she would say: "You bobbery my too muchee, my no likee so much talkee; savey? " That interpreted would mean: " You talk back too much, and I don't like it; you understand?" This ridiculous jargon used to be the only medium of conversing between the Chinese and the Europeans, and is still used to some extent; but it is dying out, and intelligible English more generally spoken, as there are English national schools for Chinese. And they themselves have established schools for the children of merchants and tradesmen in which English is taught, so that in the future there will be no need for this pidgin English.

The Chinese are a very commercial people, but the social barriers separating them from Europeans are many; besides, the language being such a difficult one for foreigners to learn, it would seem that they could not very well combine in business, and yet they do, very extensively too. To facilitate business relations a species of business man has sprung into existence, a species never heard of except in that part of the world, the Straits Settlements, and the China coast. This man is called a compradore. It sounds like a Spanish word, and has most probably been imported from the Philippine Islands. The compradore is always a Chinaman, who speaks English, and often several Chinese dialects besides. He is the middleman, the go-between in all business transactions between the Chinese and other different nationalities. Every bank has its compradore, who is a very well educated and influential man. Every European firm, from the largest house of world-wide reputation down to the smallest back street shop keeps its compradore, who does the Chinese part of the business. Every ship on the coast carries one, who manages the Chinese passenger traffic and the cargo. And every housekeeper employs one (who is a general store-keeper) to procure necessaries for the household. Indeed, the compradore is the universally-acknowledged agent between the nationalities, and to dispense with his services would be almost impossible.

The most delightful time of the year for pleasure are the months of November and December; then the island is charming, the temperature is cool and bracing, walking and all out door exercises become enjoyable. The walks over the hills and on the Peak, where many residences are built and good roads made, are as beautiful for scenery as anyone could desire. One can get on fine roads varying from a thousand to eighteen hundred feet above the sea level, and walk for many, many miles in the midst of grand views, the clear atmosphere throwing out very distant objects with great distinction. The rugged hills on the mainland rise up peak beyond peak, and far out, as far as the eye can reach, numerous islands dotting the ocean; and wending their way among the islands are what look to be tiny boats, but arc really large steamers, making their way out to sea or into this haven of rest; for at this time of the year the ships come in with their funnels white and crystallised from the spray, and their decks washed clean by rough seas. It is a hard time for ships coming from the south, for it is what is called on the China coast the north-east monsoon. The wind and the current set in from the north with great force; ships going down south get rushed down, but ships coming up against it have to struggle like giants. It makes Hong Kong and all the coast ports bright, clear, and bracing, clearing them of all the humid, bad vapours of the hot season. Everything becomes very dry; wood that has been expanded during the rainy season dries and shrivels, furniture and doors crack.

As I said before, outdoor exercise is delightful at this period, and Europeans take full advantage. Golf, cricket, and tennis are in full swing, cycling and walking indulged in more than in the other seasons. And in the houses the fires are lit, and friends gather round in the evening, and begin to talk of the homeland, and of their youthful days, and of old friends left behind. So bright and happy do we feel in this clear, dry atmosphere that it repays us in a short time for the sultriness of the summer. This is among the Europeans; I don't think the Chinese population enjoy it to the same extent; their blood is not so warm, and they are not so fond of taking exercise for pleasure as people from a temperate zone.

The result is often disastrous to them; they turn out in all their warm garments, which consist of padded coats, with long sleeves to cover the hands. These garments are frequently stored away in the pawnshops for safety during the summer. The bringing out of these old garments, and the huddling together in their small houses for warmth, gives the disease germs that have been lying idle through the summer a fair field in which to display their activity; and the consequence is that small-pox and typhoid become rife among the native population, and doctors have a hard time.

After a few months of this dryness the weather changes, and then the rains and floods come. The streams come rushing down the hillsides; strong waterways have been made, otherwise there would be great destruction to property. The streets in the city become little seas of mud; then are we glad of our chairs and jinrickshas to carry us safely through it. The jinricksha men and chair men, indeed all the coolies, go about in bare feet and bare legs to wade through it. They wear overcoats made of attap leaves; it is a thick long fringe of fine long leaves hanging from the neck. This cape, and the hat, like a huge mushroom, give them a most grotesque appearance; but the streets are lively with these queer looking individuals in spite of the rain.

This season is the breaking up of the north-east monsoon, when the winds and currents from the north abate their violence, and the south winds come, bringing the rains, and afterwards the warm south breezes, which increase in heat as the sun travels upwards towards the north. As the summer gets on towards June and July, then the fierce heat is with us. Houses can't be opened up too much, doors and windows are gaping wide to let in the smallest breeze; the thinnest of clothing can only be borne. People live as much as they can on the large verandahs, just shading them with bamboo blinds and plants from the fierce glare. In the large places of business, such as banks and offices, and also in the dwelling-houses, the punkahs (which are large fans suspended from the ceilings) are swinging. Every Chinaman carries his fan, which he uses also as a screen. The mid-day sun is terrific in its glare and heat; then it is that the people in the streets seek the shelter of the arcades at each side. The Europeans cannot walk in this baking, glaring sun, but are carried about in the chairs, with covered tops and sun blinds all round.

This fierce heat generates the tropical storms peculiar to the China Sea, called typhoons. This is a Chinese name; "ty" means large, "phoon" wind—meaning a great wind. Before these storms break, very often the heat becomes almost unbearable, the night as hot as the day; there is a great stillness, not a breath of air seeming to circulate or a leaf to move. It almost appears as if the atmospheric elements were pausing to meditate on what they should do, or looking round before they began their work of destruction. Some time before the storm bursts, the observatories in Hong-Kong and Manilla are very busy taking observations, telegraphing backwards and forwards the changes. The Hong-Kong observatory stands on a hill, and from this, and from the masthead of the " Tamar," the receiving ship stationed in the harbour, and from other prominent places, a signal is hoisted to indicate that a typhoon is blowing. If it is a red signal, not much alarm is felt in the colony; for that means it is more than three hundred miles away, and may travel in another direction from the colony. But if a black signal is hoisted, that is more serious, as that indicates it is less than three hundred miles away. And if a gun is fired, that is to warn the people that it is travelling in the direction of the, city, and may strike there. House-holders then prepare as if for a siege; doors and windows are barricaded, every movable article is taken in, all plants and shrubs in pots removed to shelter; business is suspended; ships lying in the harbour get up steam and see to their moorings; any vessel discharging or taking in cargo at any of the wharves must leave the wharf and go to some sheltered bay and anchor; all the smaller craft, cargo boats, sampans, of which there are very many hundreds, clear out of the harbour and go and pack themselves close in small bay behind the breakwater. Places of business are closed, shops shut, business men hurrying home, because the ferry boats running across the harbour and connecting the city with the peninsula of Kowloon (which is a favourite place for villa residences) stop running, and then there is no communication between the island and the mainland; all traffic stops. The last signal given is two guns fired in quick succession; that means the storm is on us.

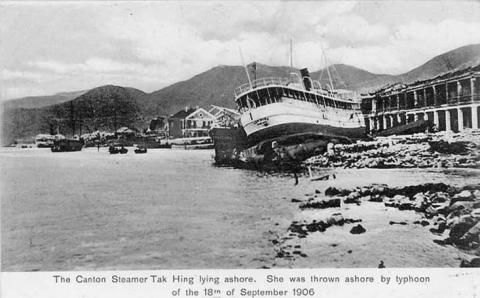

Sometimes the outside edge of this huge circular wind may just strike the colony, the centre being at sea; but if the centre travels over, then great havoc is worked. The wind comes first in sharp gusts, like squalls; these increase in violence and frequency until it bursts into a terrific roar, in which one can scarcely hear one's own voice. The sea in the harbour gets lashed into fury, and beats against the wharves, and the blocks of masonry on the quay, sometimes bringing them down. The spray from the sea is thick and blinding, sometimes accompanied with rain and thunder and lightning, all the time the wind rising and increasing in violence. This struggle of the elements lasts from twelve to eighteen hours, then begins to abate; but sometimes the typhoon, which travels in a circle, has re-curved and comes back again to the same place, and inflicts a second dose; but that is not often, and after about twenty-four hours the elements quieten down, and the city resumes its usual aspect. The sun comes out after a few hours and exhibits the destruction that has been wrought. Roofs and chimneys blown away, roads blocked with trees torn up by their roots. The shore strewn with wreckage of boats; here and there a boat drifting bottom upwards, and masts sticking out of the water where others have sunk. In an unusually severe typhoon steamers have been washed right up on to the street.

After October the season for these terrible storms passes away, and we come round to the dry season again, which I have described; and so we go round the calendar.

As I have already said, the Chinese, as British subjects, form the largest part of the population. They enjoy all the privileges of British rule; at the same time they are allowed, within certain limits, to keep up their own customs and traditions. They have their own festivities recorded in their almanacs in which everything is dated according to the moon. The first and principal of Chinese festivals is the New Year, which begins the first day of the second moon of our year, so that it oftener falls in February than not. At this festival the Europeans are obliged to take a holiday also, because no Chinaman, whatever his station in life, will do any work. For weeks before, preparations are going on among the Chinese. A respectable Chinaman must begin the New Year free from debt, so that amongst the trades people there is great activity, collecting in their accounts, and discharging their own liabilities. The last day of the year the Chinese streets are lined with stalls, selling goods of all descriptions; and the tradition is that they will make alarming sacrifices in order to draw in the money. But this is a delusion and a snare, as they are quite well aware of the universal love of making a cheap bargain among all nationalities, and so they prepare goods specially; they even make quantities of crockery to appear thousands of years old, with innumerable cracks, and bits chipped off, to beguile the curiosity hunter. The streets are thronged with purchasers; everyone buys a pot of flowers, for it is a good omen amongst the Chinese to have plants in flower at that season, and the flowers said plants are everywhere in gorgeous profusion of blossoms.

The first hours of the New Year are greeted with tremendous discharges of Chinese crackers, volley after volley, from all parts of the Chinese city, and deafening as artillery. If the Chinese were allowed to do altogether as they pleased, it would, become a great nuisance, this letting off of so many crackers; but the Government allows them twenty four hours in which to do as much as they like. After this they must moderate it so as not to annoy the other population. Then comes the feasting and visiting.

The Chinese merchant usually resides at his place of business, and there are a few of the better streets in the Chinese part of the city occupied exclusively by these men. It is very interesting to pay visits in these streets.

The front apartment of the ground floor is open to the street. It is hung with gorgeous silk embroidered banners. There is a kind of an altar in a prominent part of the room, on which pose sticks in a vase, which are kept burning all the time (this is a religious rite) ; the altar is also decorated with flowers and fancy sweetmeats (these are offerings to the spirits who preside). The master of the house sits in a square ebony chair, dressed in a brightly coloured silk or satin robe, to receive all the good wishes of his friends who come to visit him. Whether Europeans or Chinese they are received with a great amount of ceremony, bowing very low, and then exchanging the good wishes for the season. Then they offer refreshments round, sweetmeats, and their own making of wine. This goes on all day, and then in the evening great feasts are partaken of amongst themselves. The domestic servants of the Europeans expect to do no work that day. They will just put a plain breakfast and a plain dinner on the table, but nothing more; and any one newly arrived in Hong Kong, and newly starting housekeeping, will get quite a surprise, at the gorgeous apparel of the domestics. Brilliant satins and brocades are worn by the house boy and the cooks and assistants. All the Chinese houses are hung with red cloth outside, and round the hotels of the door; this has some religious origin, something symbolical of heaven. This holiday is kept up for three or four days, and then gradually subsides, businesses and trades resuming their usual round. Then on the seventh day of the seventh month, which falls somewhere about September in our calendar, there comes another big festival, "The Feast of Lanterns." All the houses in the Chinese town are covered and illuminated with hundreds and thousands of fancifully shaped lanterns. The effect is very pretty indeed—like fairyland. Every child, even the young baby, has a lantern of some kind. They are made in all kinds of fantastic designs; birds, fishes, and animals being represented. The boats in the harbour are covered, too, with these lights, making the water glitter like the firmament.

Another feast is "The Feast of Ancestors," when every Chinaman visits his father's and grandfather's or his more remote ancestors' graves, and leaves an offering there. There are no particular portions of ground set aside and fenced round as burying-places among the Chinese. They bury on the hillsides, or in the fields, wherever they can obtain a patch of ground. At this time of the year the graves are all decorated, and there are offerings of fool and imitation money and paper clothes for the departed lying on them.

The Chinese are very fond of processions of all kinds, at weddings and funerals; but they are most disorderly processions; some of the followers are walking or straggling, some running. At the funerals, one sees a coffin, covered with some rich silk embroidery, borne along by coolies in the most tattered and dirty garments imaginable; then about thirty or forty yards away some of the mourners, in their dirty white head-coverings, come strolling along, and howling in a professional manner; then a long distance behind these, running or trotting, coolies carrying tables on which food is spread.

The wedding processions are the same, part in one street and part in another havihg no apparent connection with each other. The Bride, shut up in a close-covered chair, into which no eyes can peer, may be streets and streets from the musicians belonging to the wedding or the coolies carrying banners and decorations.

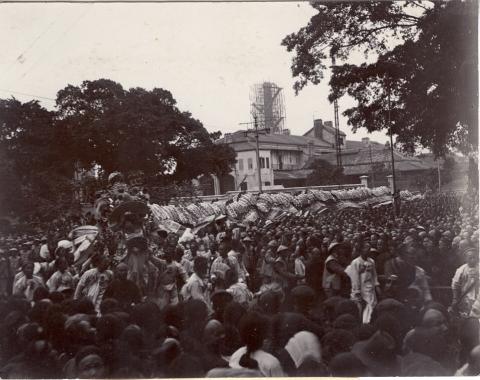

But the most magnificent of all is the "Dragon Procession", the dragon being the emblem and the guardian of China (As the Lion is emblematic of England). Of course, the British Government do not allow the Chinese to arrange these things, or to parade about just as they please; there are certain restrictions. So whenever a dragon procession is organised they have to get permission from the Government, and then they are allowed to go through so many particular streets on certain days, so that it lasts for a week or two before they have paraded through every street, and thousands of pounds are spent before they finish.

The principal feature is the representation of a huge dragon covered with silver scales, and an enormous head and tail. This is carried along by about eighty or a hundred men, whose bodies are hidden inside the frame of the dragon, only their legs showing, which look like the legs of this huge reptile; they make it writhe its body, rear its head, and lash its tail as if alive. Enormous silk banners are carried also, and silver cabinets with bells jingling; tables laid out with sweetmeats; children painted and decked out in gorgeous dresses, perched on stilts; coolies walking in most elaborately embroidered silk robes, with their dirty rags peering from underneath; roasted pigs carried whole on poles--a mixture of profusion and poverty, rich silks and dirt, tawdry tinsel trappings covering up disease But this procession and exhibition of the all-powerful dragon is supposed by the Chinese to avert calamities, and work a powerful influence for good, in some roundabout way that is not very plain to Western ideas.

Then, in return for all this toleration of their customs, they take an interest in European holidays. When Christmas come round the Chinese show their goodwill in giving us our seasonal greetings very heartily. Our servants will put on all their rich clothes on purpose to come and wish us a "Melly Clistmas," and the Chinese shopkeepers give away Christmas gifts to their European customers, and send toys to their children. And the cooks remember the roast beef and the plum pudding better than we do ourselves; they think it some part of our religion. In this way the British Government allows the Chinese subjects to live their own lives and follow out their own customs and traditions.

And thus are the barbaric splendours of the East mixed and jostled along in the streets with their more recently and more highly civilised fellow citizens from the West; Europeans and Asiatics apparently mixing together, but really going on their own separate ways, and differing very widely; for the convenience of business, and for mutual advantages, holding friendly - relations, but socially separating as far as the East can be from the West. It is a strange conglomeration, and how it will affect the future, one wonders, but cannot make any conclusions.

Thank you to David Ackerley for sharing his Great-Aunt's speech with us.

Comments

Dates of photos don't match date of story

John Latter noticed that the dates don't match - eg the Tak Hing picture is of the 1906 typhoon, but the talk is dated to 1900.

So to clarify, as far as I know the original speech was given without any photos. I've added in photos from Gwulo that illustrate the points Mrs Unsworth is making, though they're often a few years older / newer than the 1900 date.

Regards, David

DRAGON PROCESSION

David please can you give me permission to reproduce the photo of the dragon in the text above or would I need to contact someone else?

Richard

dragon procession

Hi Richard, I posted that photo; pls contact me: fuenfzigster(at)web.de. Regards Christoph