More Vignettes

Primary tabs

When we were children, the Compradore Book was an important

item of housekeeping. Every day Mamma would write in it the

food and household things needed, and the Boy or Amah would

take it to the Compradore's (Chinese grocer's shop), where the

prices would be added beside Mamma's list, and Boy or Amah would bring the various items home.

Mamma never went into the kitchen. She said it was better

not to interfere. And certainly everything worked smoothly

that way. Our food could not have been more delicious, or the

house run better. The servants were early risers, and by breakfast

time the house would be clean and tidy. But of course Mamma,

Audrey and I were away all day at our offices.

House Boys wore white jackets and trousers. Coolies also wore

white, but someimes their trousers were black. Amahs always

wore white jackets and shiny black trousers.

Considering how noisy the Chinese could be, it was amazing

how quiet the servants were. In their soft shoes they made no

sound as they moved over the bare wooden highly polished floors.

And from the kitchen no loud voices were ever heard.

In the old days every house had a filter, an earthenware jar for

filtering the drinking water in times of epidemics of cholera or

some such disease. Filtered water tasted horrid. We often had

water shortages, when the reservoirs nearly ran dry in times of

drought - then our drinking water had to be filtered too.

Soft drinks were made locally by Watson's the chemist, - lemonade,

orangeade, ice cream soda, sarsaparilla - called "sarsy-suey" by the

Chinese, "suey" being water. The bottles were light green and

closed by green marbles. To open the bottle you pushed the

marble in with your thumb, and out would come an

explosion of fizz.

When two Chinese friends saw each other coming in the street,

they could not wait to meet, but began to shout to each other,

"Wai, hai pin su-ah?" - Hello, where are you going?

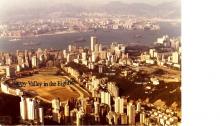

The Taipans, (heads of business firms) and their families lived in

beautiful houses on the Peak, with grand views over the sea

and islands. The bachelors' messes of the Hongs or business firms,

such as Wayfoong, (the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank,) and Ewo

(Jardine, Matheson and Co), and the others, were on the Peak too. But we envied them not, for although it was cooler up there in the

summer, they were often enveloped in thick fog, and their houses

became damp, and books and shoes grew mouldy. Wardrobes and

cupboards in Peak houses had electric lights inside to stave off

the dampness.

The wealthy Chinese lived in grand houses too, mostly: on the

slopes of the Peak and other hills to the west of Victoria.

Mah Jong was played by Westerners as well as by Chinese, but

there was a world of difference. For us it was quite an effort

to play with the Chinese and to keep up with them! They played

at high speed, notlooking at the tiles, but just feeling them, and

they would bang them down on the table without bothering to

call out the number or suit of the tile. Of course the game was

much more exciting played in this old Chinese way. They were great

gamblers, and large sums of money changed hands at Mah Jong.

They would play until the early hours of morning. The clatter of

tiles could be heard far away, especially in the summer when

everyone's windows were open. Poor Mamma used to be kept

awake by the noise, and would complain bitterly.

West Point was full of life at night. From the brilliantly lit

Chinese restaurants came loud voices and the sound of Chinese

music, mingled with the clatter of Mah Jong tiles. The Chinese

loved bright lights and plenty of noise. No wonder Hong

Kong was such a cheerful place.

A Chinese dinner at one of these restaurants was a grand affair.

Sometimes we children were invited with the grownups. The dinner

always started late, and to while away the time we ate "fa sang",

peanuts, and "kwa chee", melon seeds. You cracked the

kwa chee shells and took out the seeds with your front teeth,

and the shells fell everywhere. The Chinese restaurants were vast

places full of private rooms all engaged by Chinese for dinner

parties, and we children were allowed to wander about

the building until dinner was served. There were children in the

Chinese parties having to wait too, it seemed, because we

used to meet them in our wanderings, all of us peeping into

the other private dining rooms to see the other parties, but no

one minded. There was a great feeling of fun and gaiety and

plenty of noise and the clatter of dishes, and waiters coming in

from the kitchen with trays laden with bowls of lovely smelling

food, and sometimes the sound of Chinese music. Our dinner

began at last, everyone sitting at a huge round table, with

chopsticks and bowls, and feasting on sharksfin and birdsnest soup,

garoupa, sweet and sour pork, roast duck skin, chicken and

walnuts, fried rice', and countless other delicacies.

But honestly we liked just as much to share some of our

Amah's food at home. She used to squat on the ground

cooking it over a charcoal fire, a little fish and cabbage and

boiled rice. We loved the layer of rice that had stuck to the

bottom of the pan and was all crackly and burnt. Rich foods are

kept for parties, but everyday Chinese food is quite simple.

At the Chinese hotels and restaurants special rooms were set aside

for Mah Jong games, and also for those who wished to smoke

opium; these provided couches with small tables beside them,

both I think made of blackwood and marble. Opium was smoked

while reclining, and the little tables were for preparing the opium

pipes.

There is a memory of being stranded on a beach when we were

very young. I think it was at Lyemun Bay. Our launch had to

go away on business and the coxswain promised to return soon.

Afternoon came, and no launch - and evening came, and still

no launch! The sun set and darkness began to fall. We all

sat at the top of the beach, waiting and wondering. The night

insects came out and began to make buzzing noises in the

bushes behind us. How thankful we were when the launch arrived

at last!

Our newspapers were the South China Morning Post, the Hong

Kong Telegraph, and the China Mail. Young Chinese boys sold

them in the streets, calling out "Mor Po", "Te Ga", "Chai Mei"!

Our favourite fruits were the laichees, persimmons and tangerines,

and all the children loved the sweet juicy sugar cane. It was

sold in pieces several inches long, and we bit off pieces and

after chewing them spat the remains out on the ground.

Causeway Bay near our Convent was a typhoon shelter for junks

and sampans, being an especially sheltered bay. It was a

favourite place at all times with the junk people - those who

lived their whole lives in junks - and we would see their

sampans yulo-ing people back and forth to the junks. A sampan

was propelled by a man or woman standing, moving the single

oar back and forth - this was to "yulo". We saw the fishermen

pulling in their nets, wearing the usual large straw hats,

white jackets and black or brown trousers.

Typhoons were awe-inspiring happenings. At the first sign of

the coming of a typhoon, signals were hoisted, so that people

could prepare, The sampan and junk people took their boats to

the typhoon shelters, and the Naval and merchant ships went to

the middle of the harbour to "ride out" the storm. Typhoons

came in the heat of the summer. At first there was a queer

stillness, a dark grey sky and a little rain.

Offices and shops closed, and everyone hurried to catch the

last ferries or trams to get home. Then the last signal went

up, and our houses were made safe by closing and barring

the wooden shutters over the windows, and shutting every

door. The rain came, and the wind started blowing, harder and

harder. It was so hot indoors with everything closed up, we

felt stifled. And the wind howled and shrieked, and trees

were uprooted, branches torn off, and everything loose in the

streets would fly. People were knocked over - you couldn't stand

in such a wind - and sometimes ships were sunk in the

harbour. Once Audrey and I tried to go outside our house in a

typhoon, but we were soon knocked over and had to crawl back

indoors. We were lucky not to be hit by flying debris.

In a few hours the typhoon was over, and people left the

shelter of buildings to see the most awful scenes of devastation.

Trees and branches and pieces of houses and all kinds of

things lying about, and everything was wet, and the air felt hot

and wet too. "Typhoon" comes from the Chinese "dai fung",

meaning "big wind".

Cloth Street was a collection of little open-fronted shops, selling

pretty flowered cotton material in great variety. The Chinese

women bought cloth here for their dresses, and we did too

when we needed something unusual. Once Audrey and I went to a fancy dress party dressed as "Early Victorian" ladies, wearing

elaborate gowns made by our tailor and his assistants out

of material from Cloth Street. But they were used to making our

long evening dresses, so nothing deterred these clever men.