In the second of Mary Unsworth's memoirs, she tells us about Chow Sing, the Chinese steward on her husband's boat. (Her husband, Richard Unsworth, is the "Captain" in the following text). Chow Sing suffered greatly when the plague hit Hong Kong, but in an unexpected twist the story has a happy ending.

"Chow Sing" by Mary Unsworth, copied from her original handwritten account.

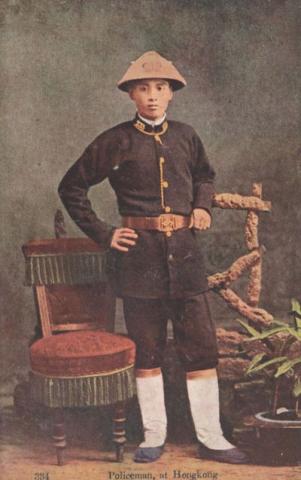

Chow Sing had been a steward on board the SS Keong Wai, a British vessel trading from Hong Kong, a few years when I was introduced to him. First he had been the Captain's boy, then after very faithful service was promoted to steward. He was a short man, with a large head, small oblong eyes, typical parchment face, but his great charm was the double jaw of beautiful white teeth, which he showed very frequently, for he was always smiling, a good open smile all over his face. He was always scrupulously clean, and it was a great point with him to dress according to his position, when he was a boy he only wore the full white trousers and short jacket, but when he became steward he at once donned the long coats such as tradesmen and merchants wear, made of the finest grass linen, a cleanly shaved head, with smoothly plaited pigtails, neat white stockings and the thick soled (illegible word) Chinese shoes.

Chow Sing rather prided himself on his literary accomplishments, he had travelled in Europe as servant to an Englishman, had picked up a bit of French, which he was very fond of using, if the ship went to Haiphong or Saigon, or took any French people passengers. Then would he produce the most fearfully worded menus for the dinner table, that he could possibly devise. The names of the dishes were given in French, but spelt in phonetic English, it was entirely hopeless to read it. But such a favourite was Chow Sing always with passengers and crew, that no one was ever so unkind as to laugh in his presence. The passengers would look at the menu, and then look at the Captain, and the Captain with a very solemn face but just a merry twinkle at the corner of his eyes, would say, "Oh, Chow Sing, you know I can't read French, what is this thing here". Then Chow Sing would tell them the word in his best French accent, and then translate it into common English, so that they at last arrived at an understanding.

He read a little and wrote in English, the Captain has letters in his possession that he received at various times from Chow Sing. They are copies of a plain business letter but interspersed here and there with Oriental phrases, enquiries after the health of all the receivers' relations, asking leave to present his compliments many times over, then formally signing himself as 'Your disobedient servant'. Chinese etiquette didn't allow him to presume to designate himself as an obedient servant.

His politeness was charming in its simplicity. If obliged to pass a European, he would say "Accuse me". And when sent by his master with a present of fruit to a friend, the gentleman told Chow Sing how grateful he was for his kindness, Chow Sing smiled all over his face exposing his gleaming white teeth and replied, "Don't mention it Sar". All bodily discomforts he bore with Chinese stoicism. When storms came and brought all the usual miseries, the English officers would be growling, muttering curses on the weather and the sea, and denouncing all who went thereon. Chow Sing might be washed out of his bunk, see his fowls and sheep, (which were his own property) swept overboard, still he would never utter a murmur, but would go silently about with his usual calm imperturbability, gathering together his few possessions that he could save, and whenever he could get near a fire, making coffee for the Captain, whom he adored, and taking it on the bridge to him.

When the Captain went his periodical round of the ship, rooting into corners, finding fault everywhere, sometimes Chow Sing would come in for his share of complaints, something was wrong in his management of stores etc. But that never made him waver in his allegiance to his master, he was devoted to him and nothing would make him doubt his perfection. If he had found fault with more than usual, he would say nothing, but go quietly to the Captain's wife, and make excuses to her, for the master Captain having a little bit of temper, "Only a bittey temper". Then he would begin to sing his praises saying "What a number the Captain he has. He likee all man number one, likee all thing very proper". Indeed, so true was his attachment to his master that several times he had refused higher wages to leave and go to another ship, and once in an American port he was offered a large sum of money if he would run away. The temptress would assist him to evade the officers who were watching to see that a ship from China brought no Chinese into the country, but Chow Sing knew that if he had escaped, his Captain would have had to pay a fine of five hundred dollars, he refused all these offers with contempt.

Chow Sing was not without troubles as he grew older. His wife had had several children, but delicate and had died in infancy, except two sons, one a sickly youth who appeared likely the others, and a young baby. The loss of his children was a great grief to him, for, besides being a naturally an affectionate man and fond of his children, he had the ambition of all Chinamen, rich or poor, to leave sons behind him to perpetuate his memory and do him honour.

When his eldest son began to droop, he asked leave of the Captain to go to Canton for a few ((?)) consult a celebrated Chinese medicine man. The Captain, with direct bluntness, told him he was a fool to go to this medicine man, whose remedies were dried cockroaches, powdered toads, advised him to go to a good English doctor who would tell him how his son should live to get strong. But no, Chow Sing was obstinate. In spite of his intelligence, and belief in his master's wisdom, he clung to the traditions of his country thousands of years old. So he went to the Chinese Canton who prescribed doses of rhinoceroses horn for his son, instead of fresh air and nourishing food. So the sick boy was kept in a dark stuffy street full of foul air, and Chow Sing stinted himself and his family to buy the precious medicine (which is placed in the scales with gold to balance it, as the price so valuable is it), with the result that his son drooped more and more and eventually died.

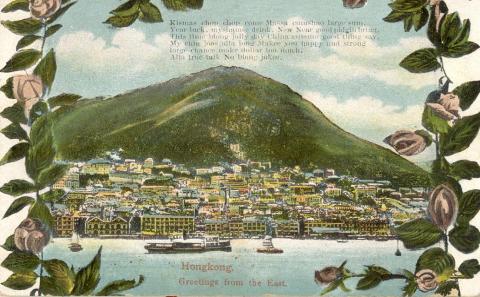

Poor Chow Sing felt that bereavement very much. But after a time he recovered his cheerfulness and concentrated all his affection on his remaining son, a child of eighteen months. But an unkind fate still pursued the good natured simple hearted man. In 1894 the plague broke out in Hong Kong, and spread and grew with alarming rapidity. The Chinese were panic stricken. When we came into Hong Kong at the beginning of June, Chow Sing intended to break into his house which was in the centre of the Chinese part of the town, and send his wife and son up to live with some relatives out in the country. But the ship was discharged and ordered away again in a great hurry before he had time to make the necessary arrangements for them going, so unfortunately he postponed it until we came back again, as we were only to make a short trip, three weeks at the longest.

We came back to Hong Kong within the time. Early in the morning we entered port, I saw Chow on deck, going about in his noiseless way, getting baskets together to go to the early markets, then I saw him enter a sampan to go on shore as soon as ever we were moored. In the afternoon I was on deck, watching the discharging of the cargo, when Chow Sing came to me, but what a change! Whatever had come over the little man? Instead of his usual tidy appearance, his clothes were disordered and awry, tears were streaming down his face and he could scarcely be asked to tell me his trouble, at first he could only say "He wanted the Captain, would on board soon, must go Canton chop chop". After a while I gathered from his more broken than usual English owing to his agitation what the matter was. Whilst we had been on our voyage, his wife had been seized with plague, taken to the hospital, died and been buried, his house broken into, furniture confiscated and burnt. The whole street where he had lived had been condemned by the Sanitary Board, all the inhabitants after a strict survey had been scattered, and the street closed up, all the homes eventually to be demolished. He didn't much care about his furniture, but the worst was, he couldn't find his little son. Some other persons who had lived in the same house as his wife were also in the plague hospital, these he couldn't go near to ask, and of the others most of them had fled to Canton, afraid of the plague, but more anxious to escape the Sanitary Board. Only one neighbour's family could he find in Hong Kong, he had been to them but they couldn't tell him anything about his child, but they thought someone had taken him away to Canton. Poor Chow Sing, he was in despair, he wanted the Captain to let him go away at once, he would catch the night boat. In the midst of his troubles he didn't forget his duties, he had brought a friend with him to act as a substitute in his absence, and had explained to him the usual routine of the table, the Captain's likes and dislikes etc.

It wasn't long before the Captain came on board, and after hearing Chow Sing's sad tale at once released him from his duties, gave him back as much of his savings that he had been taking care of wanted; he wouldn't take all, as he didn't want to carry much money, and when he could send for it. So he went away, and not only did we miss his smiling good tempered face, but we couldn't find his equal as a buyer and caterer for the table. The substitute he had brought soon had to go, as he wasn't as clean and energetic as Chow Sing had been, he made way for another, and that one for another, and so we went on changing voyage after voyage. We couldn't find another Chow Sing, who had spoilt us and made it impossible to put up with the incapable ones that succeeded him.

The first month after he had left the cook received a letter from him in which he begged leave to present his compliments to the Captain and all the officers, but after that we heard no more, and we began to fear that Chow Sing had fallen victim to the plague that was still raging worse than ever in Canton. After nearly eight months absence, one morning he came on board in Hong Kong, and without saying much to anyone began going about his work as steward, on his own account he paid off the one then acting as such, and went about his duties as if he had only been away an hour or so. When asked if he had found his son he shook his head but declined further information. He was changed in appearance, much older looking, his steps were slow and heavy, his jet black pigtail was streaked with grey, his smile was gone, we didn't see his gleaming white teeth as often, and according to the mourning etiquette of the Chinese he clothed himself in the dirty yellow (Illegible word) that they wear for mourning, which didn't give him such a spotless and clean look as formerly, but otherwise he was as good a steward as ever, and we found it a great comfort to have him back and catering for us again, after the poor and indifferent ones we had put up with whilst he was away.

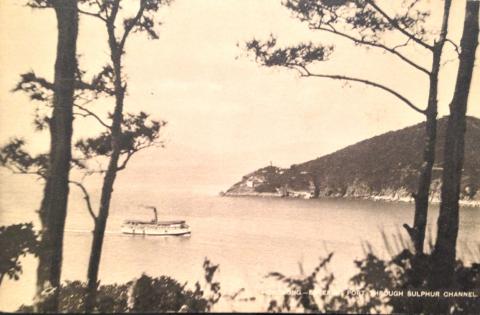

During the height of the plague, all coolie emigrations from China had been stopped, but as it began to abate in '95 towards the close of the year the restrictions were removed, and under certain regulations we were again allowed to carry coolie emigrants. So in November we were ordered to Swatow to take 600 coolies down to Singapore. Now Chow Sing, who as I remarked was very fond of children, used to take notice of each passenger's children, talk to them and give them presents of fruit or sweetcakes. On our way from Swatow he was attracted to a small boy of nearly three years old, a bright little fellow; on talking to and questioning the father he found out that he wasn't the real father, but that he had bought the child from a poor woman who was near dying for the sum of ten dollars. This is not an unusual occurrence, poor people will often sell their children to someone who is better off, and wishes to possess one or more, especially boys, a baby boy will always find a ready purchaser, so in this case.

As we got into the hot weather down south, the children threw off all superfluous garments, with little or no clothing. Then it was that Chow Sing noticed a very peculiar birth ((mark on a)) child's back, which was identical with a mark that his own child had had. Further questioning of the assumed father as to when he bought the child, and he found that the time corresponded with the date of his own son's disappearance.

Chow Sing became convinced after more searching and questioning that this was his own lost child and made an offer to buy him back, but the passenger's cupidity and avarice were then awakened, when he found the child was so largely desired nothing would tempt him to sell. The higher the price offered the more determined he was in his refusal to part with the child. Twenty dollars refused with a doubtful shake of the head, but a hundred dollars he rejected with unutterable scorn. In (illegible word) Chow Sing had kept raising the price, but when he reached the one hundred dollars he stopped, as that was more than he possessed or could conveniently borrow. Then he appealed to the Captain. The Captain was in a dilemma also. It was no use to take back to Swatow and institute law proceedings to get back the child. The bribes that would have to be paid to the Mandarins and court officials would cost a small fortune, besides who was to watch the passenger with the child so that he didn't run away while the trial dragged on.

Even to detain the passenger in Singapore longer than necessary would involve the Captain in a lot of trouble and expense with the officers of the immigration code. So he knew he must resort to strategy, try a game of bluff, and very quickly too as we were only twenty four hours reaching from Singapore. So, calling the Comprador (the Chinaman who acts as kind of supercargo on ships that trade on the China coast) he began to question him about the passenger. Didn't the Comprador remember travelling in the ship before? The Comprador wasn't quite sure. "Well" said the Captain, "you go and find out, I think he's the passenger who came down in this ship eighteen months ago, and escaped out of the ship whilst she was in quarantine and got on shore before the time had expired, mind you I think he's the same man, and if he is I shall take him into custody now, you go find out something anyway". The Comprador, an astute impassive Chinaman, knew the drift of the Captain's remarks without more questioning and went away to do his bidding.

In an hour or so he came back to report. By making many enquiries among the other passengers ad found out something about the man. They couldn't charge him with attempting to escape quarantine but he had travelled down to Singapore two years ago, his passage paid by the coolie broker, whom he was to work for and pay off the price of his passage. But he had run away from the broker's agent in Singapore and never worked up the price of the passage money paid.

The Captain then called up the passenger before the Comprador and the steward, then he told Comprador to explain in Chinese to the passenger that they knew he was the man who two years had escaped from the broker's agent without paying his passage money, and that if he didn't let Chow Sing have his child back at the first price offered, namely twenty dollars, then he (the Captain) would keep him in the ship in Singapore until he found that same broker's agent, and give him in charge. The man couldn't fight after that, he knew that to be given over to the tender mercies of a coolie broker to work up a passage money that he had tried to escape from paying meant nothing less than slavery for a few years, and that the amount of the passage money would be extorted a hundred times over. He sulkily agreed to take the twenty dollars and give up the child, which Chow Sing willingly paid. So Chow Sing recovered his child and became a happy man again. He soon recovered his cheerfulness, he even bought another wife and had some more children, he also went into partnership with a friend who had a stall in the market and prospered, tho' he still continued on board the SS Keong Wai as steward, nothing would make him desert his Captain whilst ever he went to sea, where the Captain went Chow Sing would go too. So he is still going about the China coast, and his son who was lost and recovered, whose name is Ah Sing is at the British School in Hong Kong where he is learning to be a scholar, as it is his father's ambition that should qualify for the post of Comprador on the SS Keong Wai.

Thank you to David Ackerley for sharing his Great-Aunt's speech with us. I wonder if Ah Sing lived up to his father's hopes, and gew up to become the ship's comprador?

|

Also on Gwulo.com this week:

|