Chinese photographers in Hong Kong, 1844-1879

Primary tabs

The following text and images originally appeared as chapter 6 of "History of Photography in China: Chinese Photographers 1844-1879", published by Bernard Quaritch in 2013. (Click here for more information about the book and how to order.) This is Volume 3 of Terry Bennett's work on China's photo history. They are reproduced here with the kind permission of the author and publisher.

Chapter 6

Photography in Hong Kong

Hong Kong was ceded to Britain by China under the Treaty of Nanking (Nanjing) in 1842.1 It was, therefore, a formal colony over which China had no sovereignty. A small island with a deep-water harbour and well placed for establishing a trading outpost on China’s doorstep, it had previously been of little economic importance and only lightly populated by the Chinese. Very much a colonial creation and a place quite unlike anywhere else in China, Hong Kong was full of contradictions and variety, as a British diplomat en route to Peking (Beijing) remarked in 1865:

Hong-Kong presents perhaps one of the oddest jumbles in the whole world. It is neither fish, flesh, fowl, nor good red-herring. The Government and principal people are English – the population are Chinese – the police are Indians – the language is bastard English mixed with Cantonese – the currency is the Mexican dollar, and the elements no more amalgamate than the oil and vinegar in a salad. The Europeans hate the Chinese, and the latter return the compliment with interest. In the streets Chinamen, Indian policemen, Malays, Parsees, and half-castes jostle up against Europeans, naval and military officers, Jack-tars, soldiers, and loafers of all denominations.2

The 1866 census gave Hong Kong’s population as 115,000 people, of whom 2,100 were Europeans.3 This made it the largest concentration of Western residents in China at the time, especially in relation to the size of the local population.

Hong Kong by 1870 had one of the highest ratios of police to population of any part of the British Empire.4 Of special note for photohistorians in this context is the introduction of photography for police records of Hong Kong’s Chinese population, which is referred to in John Thomson’s article on ‘Hong-Kong Photographers’ published in the British Journal of Photography in 1872. Thomson said that Hong Kong, ‘gradually throwing off its old bad habits under the liberal and enlightened government of our land’, now possessed ‘great stone institutions that frown on and furnish slender fare to evil-doers’, and:

above all, as interesting to the readers of this Journal, it utilises the camera to register the faces of its convicts – a thing which the latter do not take to, as they fancy that the process deprives them of a certain portion of their vitality. This is a very wholesome superstition if they value their lives; and, as they know if they do not contrive to look like somebody else when being photographed, it places a dangerous weapon in the hands of the law, as Chinese faces are not all alike, but sufficiently different to impart a marked character to each.5

Rather than being employees of the police force, it is likely that this work would have been undertaken by local commercial photographers, who would have tendered for official contracts. This was the usual practice elsewhere in the world until the 1890s.6 The Hong Kong colonial government later devised a system of photographing registered prostitutes, and women and children who intended to emigrate. This, the Governor, Sir George Bowen reported in August 1883, had ‘done much good’, with an ‘enormous reduction’ in kidnapping and ‘selling women for prostitution since the introduction of these measures’.7

Commercial photographic studios were active in Hong Kong from the mid 1840s. The earliest known is that of the American, George R.West, who advertised his daguerreotype studio in the China Mail on 6th March 1845. A number of other Western photographers subsequently visited the colony, but it was not until February 1860 that the American professional photographers, Weed & Howard, set up anything approaching a permanent studio.8

The first clear evidence of a Chinese photographer operating in Hong Kong is an advertisement placed by the Kai Sack studio in the Hongkong Daily Press on 6th April 1864. This is some twenty years after the first appearance of George West’s studio, and it would therefore be surprising if future research did not discover traces of earlier Chinese studio activity. The Ye Chung studio, for example, may well have been in operation by 1862 or even earlier, while in the early twentieth century the Afong studio claimed that its founder, Lai Fong, had established the business in 1859.

In the 1840s a number of Chinese artists established themselves as portrait painters in Hong Kong. This process accelerated in the 1850s as an influx of Chinese families from nearby Guangdong province moved to Hong Kong to escape the chaos of the Taiping Rebellion. Many of these painters subsequently added photography to their range of services.9

Lai Fong (c.1839–1890) and the Afong Studio

The most successful nineteenth-century Chinese commercial photographer was the Hong Kong-based Lai Fong 黎 芳 or ‘Afong’, to use his professional style and studio name.10 Lai Fong was the one Chinese photographer that nineteenth-century Westerners were likely to have heard of and he enjoyed the highest reputation. His erstwhile competitor in Hong Kong, John Thomson accorded him exceptional status:

Judging from his portfolios of photographs, he must be an ardent admirer of the beautiful in nature; for some of his pictures, besides being extremely well executed, are remarkable for their artistic choice of position. In this respect he offers the only exception to all the native photographers I have come across during my travels in China.11

We know little about Lai Fong’s early life, except that his family was from Gaoming, to the west of Foshan in Guangdong province, and he came to Hong Kong to escape the turmoil of the Taiping Rebellion.12 Early twentieth-century notices of the Afong studio state that it was established in 1859,13 but no such claims were made in Lai Fong’s lifetime and they perhaps stem from confused family tradition after his death. Much more probable is that 1859 was the year when, aged about 20, Lai originally entered the photographic profession, perhaps as a trainee or assistant to a Western photographer, in, it may be supposed, Canton (Guangzhou) or Hong Kong.

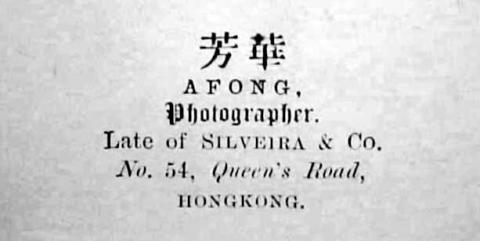

Some of Lai Fong’s cartes de visite from the early 1870s have ‘Afong, Photographer. Late of Silveira & Co.’ printed on their reverse.

Fig. 6.1. Reverse of a carte de visite showing the Afong studio imprint

with the reference to Silveira & Co., c.1870. Author’s collection.

This indicates that at some time between 1865 and 1867 he worked at the Hong Kong studio owned by José Joaquim Alves de Silveira, who had purchased the business from S. W. Halsey & Co. in June 1865. In early 1867 Silveira in turn sold out to William Floyd, who had for a short while before been his operator.14 Perhaps Lai parted company with Silveira at about this time and commenced his own career as an independent photographer. In any event, the earliest known announcement of his studio’s services is an advertisement dated 9th April 1870 published in the Hongkong Daily Press on 11th April 1870:

|

PHOTOGRAPHY A LARGE Collection of VIEWS taken at Foochow, 54, Queen’s Road, Opposite the Oriental Bank, |

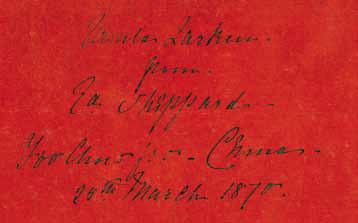

While Lai Fong’s statement that he would welcome ‘a visit from his old friends and the community’ suggests he was known as a photographer in Hong Kong by 1870, this advertisement is the first evidence we have for the formal establishment of the Afong studio as an independent business with its own premises. Besides studio photography, usually in the form of cartes de visite, which was the mainstay of much of the photographic trade in China at this time, Lai Fong offered for sale a superb series of views of Foochow (Fuzhou) and the vicinity of the River Min (see Chapter 9). It is probable that he put this series together in 1869, because an album, now in the author’s collection, of sixty of these views is inscribed ‘Ursula Larkness from Ed. Sheppard, Foochow, 25th March 1870’ (Edward Sheppard was a clerk with Russell & Co., an American trading firm whose Hong at Foochow is the first picture in the album).

Fig. 6.2. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). Front cover of an album of

sixty views of Foochow (Fuzhou) and the River Min, 1870.

Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.3. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). Contemporary inscription,

dated 25th March 1870, inside the album shown in fig. 6.2.

The contents of this are largely complementary to another album, also in the author’s collection, with forty views, which has a printed yellow studio label inside the front cover, ‘From Afong, Photographer, No. 54 Queen’s Road, Hongkong’. Only seventeen views are common to both albums, while the printed captions and numbering indicate that the full series comprised well over 100 images. A third album, in the collections of the National Galleries of Scotland, contains fifty-two views, as well as two other photographs, which were probably not part of the original series: ‘Grand Stand, Foochow Races, Autumn Meeting 1869’ and ‘Our new Club House, just opened, January 1870’. Pasted into this album is a signed portrait photograph of Lai Fong himself.15

Fig. 6.4. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). Front cover of an album of

forty views of Foochow (Fuzhou) and the River Min, c.1870.

Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.5. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). The printed

studio label from the album shown in fig. 6.4.

Fig. 6.6. Anonymous. Portrait of Lai Fong, c.1869. Cabinet-sized

albumen print, the mount signed in English, ‘Afong’, and in

Chinese characters, 芳 華 [Fong Ah], and inscribed ‘Ye Portrait

and Ye Autograph of Ye Artist’. This is one of only two known

likenesses of Lai Fong (see also fig. 6.40).

Scottish National Photography Collection (ref: PGPR 871.1).

Lastly, an album of over 130 views (and a few portraits) by various photographers appeared at auction in 2012, which included a photograph of the ‘Foochow Races. Spring 1869’ signed ‘Afong’ in the negative.16 This means that we can now confidently say that Lai Fong was working as an independent photographer, actively photographing in the Foochow area, by the second quarter of 1869.

Besides Foochow, Lai Fong offered views of Hong Kong and treaty ports such as Canton (Guangzhou) and Swatow (Shantou), as advertised in the China Mail on 25th May 1870 (he ran this advertisement for over a year):

|

AFONG, Invites Inspection of his large Collection of VIEWS Hongkong, |

The Hong Kong photographic market at this time was highly competitive. Apart from the studios of John Thomson and William Floyd, a growing number of Chinese photographic establishments were opening, notably those of Pun Lun, Hing Qua John & Co. and Ye Chung. Price wars had been eroding the profits of Thomson’s and Floyd’s studios since mid 1868. The establishment of the Afong studio in April 1870 further increased the commercial pressures on Thomson and Floyd, especially as they now had a serious competitor in the sale of photographic views of China, a field that had previously been avoided by Chinese studios in favour of portraiture. Like Floyd, Lai Fong sometimes offered his photographs for sale by raffle.17 Thomson returned to Britain in 1872, Floyd moved to the Philippines, where he established a studio in 1875.18 At the beginning of 1875, therefore, two of Lai’s strongest rivals had gone, but he still had to contend with Emil Riisfeldt of the Hongkong Photographic Rooms,19 well over twenty Chinese studios, and persistent economic depression in the colony.

Aside from his keen pricing and the excellent quality of his work, Lai Fong promoted his studio by assiduously cultivating the colony’s foreign residents and visitors. When he began his Hong Kong studio career, foreigners, as we have seen, generally had a low opinion of the skills of Chinese photographers. Although his talents came to be recognised as exceptional, Lai was careful to counter prejudice by reassuringly employing a series of respected Western photographers in his studio. Among these were Emil Riisfeldt and David Griffith, both of whom went on to open studios in direct competition with their former employer.20

Lai Fong, more it would seem than any other Chinese-owned Hong Kong studio, advertised extensively in the local English-language newspapers and trade directories. He introduced new stock, advertising, for example, some views of the West River (Xi Jiang), in the China Mail on 2nd January 1872:

|

AFONG, INVITES Inspection of his large Collection of Also, Some nice VIEWS of the WEST RIVER OF CANTON. Hongkong, |

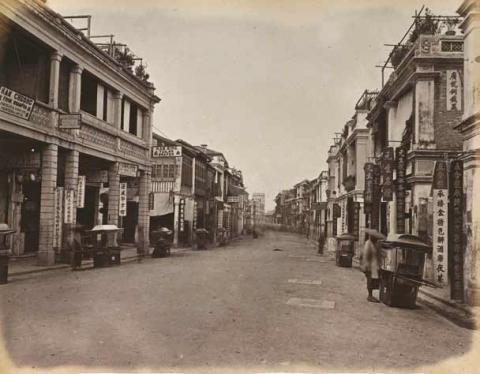

Fig. 6.7. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). ‘Hongkong. 319. – Queen’s Road

Central’, 1870s. Private Collection.

In December 1872 Lai moved his studio from Queen’s Road to nearby 3 Wyndham Street.21 By now his professional pre-eminence was firmly established, as John Thomson recognised unreservedly:

There is one Chinaman in Hong-Kong, of the name of Afong, who has exquisite taste, and produces work that would enable him to make a living even in London. Afong is, however, an exception to the general run of his countrymen, as their peculiar views of what constitutes art in a picture are quite opposed to our foreign prejudices and to all that we have been taught to recognise as art.22

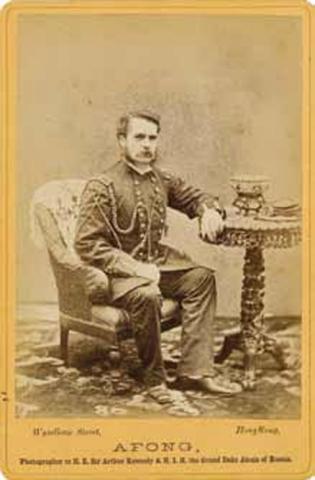

Fig. 6.8. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). Portrait of an

unidentified foreigner with the Wyndham Street

studio credit, c.1875. Cabinet card photograph.

Author’s Collection.

Lai Fong photographed notable local events, such as the typhoon of ‘unprecedented suddenness and power’ that struck on 22nd–23rd September 1874, leaving the island ‘looking as if it had undergone a terrible bombardment’ and over 2000 ‘lives lost in the harbour in the space of about six hours’.23 He

captured the devastation in Hong Kong and in nearby Macau (Aomen) in a fine series of views. The printed introduction claimed:

The following Sketches illustrate some of the worst features of the destruction at Hong Kong and Macao. The most numerous, the largest, the most complete and most comprehensive series of Photographs of the kind published, they convey an excellent idea of the effects of the Typhoon.24

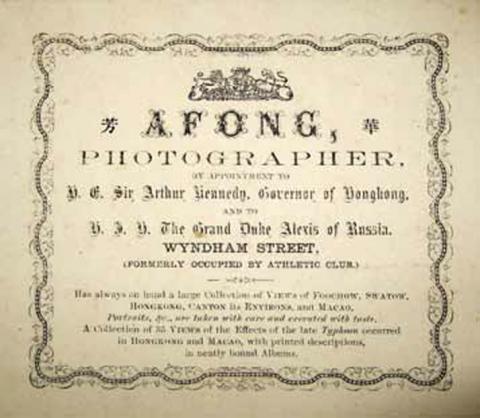

Fig. 6.9. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). Studio credit label pasted inside the front

of an album, c.1874–75. The reference to the collection of views of ‘the late

typhoon’ gives an approximate date as this natural disaster struck Hong Kong

and Macau (Aomen) on 22nd September 1874. Private Collection.

Fig. 6.10. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). ‘19. – Destruction of Ball’s Court [Hong Kong]’, 1874. From an album of 35 views of the typhoon of September 1874.

A competing series of views of the same event was issued by William Floyd’s studio. Serge Kakou Collection.

Fig. 6.11. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). ‘2. – Destruction of Douglas Lapraik’s Wharf [Hong Kong]’, 1874. Serge Kakou Collection.

By this time Lai Fong’s work was beginning to reach an audience beyond Hong Kong. His photograph of the new Royal Naval Hospital at Hong Kong was published in the Illustrated London News on 27th September 1873 (p. 293) with the credit, ‘The engraving is taken from a picture drawn by a Chinese artist, whose name is Afong’.25 His talents received increasing public recognition. John Thomson, now no longer competing in Hong Kong, continued to praise him in the description of his travels in China published in 1875.26 In 1875 David Griffith said that ‘Mr. Afong’, unlike the Chinese photographers of Shanghai,‘has entered the arena of European art, associating his name with photography in its best form, and justly stands first of his countrymen in Hongkong’.27

In the autumn of 1875 Lai Fong journeyed to Formosa (Taiwan), bringing back a notable series of photographs (see Chapter 14).28 This was reported in the North China Herald on 25th November 1875 (p. 520), which also reveals that he was taking portraits of the residents of Kulangsu (Gulangyu), the foreign settlement area of Amoy (Xiamen):

Mr. Afong, photographic artist, has lately returned [to Hong Kong] from the interior of Formosa, with a collection of mountain sceneries, lakes, rivers, etc., not taken by anybody before. He has also photographs of the famous granite bridges at Chin Chew, the largest, I presume, about 1½ miles in length. He is now busily engaged with the ladies and gentry of the beautiful

island of Koolunsoo.

Despite his burgeoning reputation, Lai remained keen to reassure potential customers that the studio was staffed by experienced photographers, such as the American William Lentz, as he advertised in the ‘Japan Gazette’ Hong List and Directory for 1876:

N.B. – Having secured the services of Mr Wm. H. Lentz, for a term of years, my customers can rely upon being treated with the utmost courtesy, satisfaction being guaranteed in all cases or no charge.29

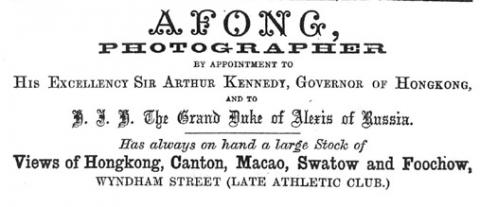

Lai Fong secured photographic sessions with various notables, which both reflected and enhanced his reputation. He photographed the Grand Duke Alexis of Russia, who visited Hong Kong in September 1872, and Sir Arthur Kennedy, governor of Hong Kong from 1872 until 1877. The patronage of both these dignitaries was proudly referred to in the studio’s advertisements, and for many years the studio’s cartes de visite and cabinet cards had printed on the back: ‘Photographer to H.E. Sir Arthur Kennedy K.C.B. [and] H.I.H. the Grand Duke Alexis’. As well as such distinguished patronage, the broad range of the Afong studio’s services and stock and its use of the latest photographic equipment from England is well illustrated by this advertisement (which also notes the departure of William Lentz) in the ‘Japan Gazette’ Hong List and Directory for 1877:

|

AFONG, PHOTOGRAPHS of any size taken; outdoor work N.B. – A new apparatus for Photography has been Mr.W. H. LENTZ is no more attached to the Studio. No. 3A, WYNDHAM STREET (formerly the |

Fig. 6.12. Afong Studio advertisement from the China Directory, 1873.

Fig. 6.13. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). Westerners in theatrical costume, 1870s–80s.

Cabinet card photograph. Author’s Collection.

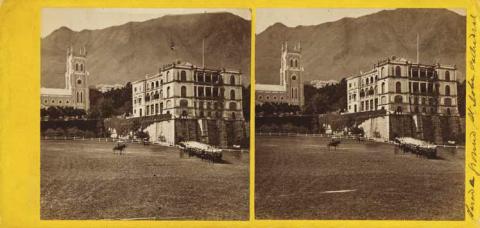

Fig. 6.14. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). ‘Parade Ground, St. John’s Cathedral

[Hong Kong]’, c.1875. Albumen print stereoview. Photographer’s

blindstamp ‘Afong’ on the left print. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.15. Lai Fong (Afong Studio).‘Japanese Moosmi [young woman] 1873’.

This is from a small series of portraits of Japanese sitters taken in the Afong

studio in Hong Kong (see also fig. 6.16). Note that the same chair appears in

fig. A52. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.16. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). ‘Japanese Moosmi 1873’. Another print

of this image is also in the collection of the Wilson Centre for Photography

with a printed caption label reading ‘No. 28. A Japanese Lady, wife of one of

fthe principal Merchants in Japan.’ Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.17. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). Japanese lady, Hong Kong, c.1873.

Wilson Centre for Photography.

On 29th April 1878 the China Mail announced the move of the Afong studio from Wyndham Street (as listed in the 1878 Chronicle & Directory for China, Japan, the Philippines &c.) to 8 Queen’s Road Central.

In the autumn of 1879, Lai Fong was in Peking (Beijing) photographing the foreign ministers meeting in the capital and taking a series of views. This was recorded in the London and China Telegraph on 19th January 1880 (p. 51):

Diplomatic conferences are over for the season, and concluded with photographic groups of the twelve Ministers and chargé d’affaires. The photographer, A. Feng [sic], is here from Hong Kong, and has taken many excellent views, notably a view of the Imperial Throne or, rather, large chair, with carved lacquer and mother-o’-pearl screen at the back, occupied by the Emperor during the ceremony.

Fig. 6.18. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). ‘No. 858, The Dragon Throne Pekin. The

Imperial throne of the “Son of Heaven” is here illustrated but unfortunately

without its august occupant . . .’, 1879. Author’s Collection.

On 23rd July 1880 the London and China Express reported (p.771):

We noticed recently that at the meeting of Ministers of Foreign Powers at Peking last autumn, Afong, a photographer, of Hong Kong, took a photograph of the group of Ministers. We have received a copy of this photograph, and must say that it is very well taken indeed. [see fig. 4.4]

Sir Arthur Kennedy’s successor as governor of Hong Kong, Sir John Pope Hennessy, had an informal portrait of himself taken soon after his arrival in April 1877, ‘leaning against a carved balustrade and holding his stick and his top hat in his hands, by the Afong Studio in Victoria’.30 In 1879 Lai Fong took a formal portrait of the retiring District Grand Master of the Hong Kong Masonic Fraternity. This occasion was described in the North China Herald and S. C. & C. Gazette of 7th November 1879:

When Mr. T. G. Linstead, the District Grand Master of the Masonic Fraternity of the Hongkong district, left the Colony for Home, Mr. Afong took his photograph in full Masonic regalia in order that the Masons of the place might have a painting of the D.G.M. to adorn the Masonic Hall. Mr. Griffiths [sic], Mr. Afong’s manager, has just finished a photograph in water colours, an enlargement from a carte de visite of Mr. Linstead. The likeness is strikingly lifelike and the work reflects great credit upon the artist.

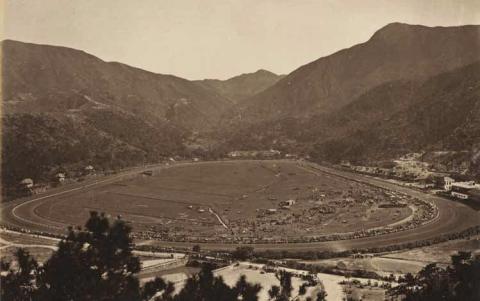

Fig. 6.19. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). ‘No. 267. – Race Course. As seen from

Morrison’s Hill - the buildings on the right are the New Stand, and Matsheds

or Stable, used during race times by the owners of horses. - The length of the

course is 3/4 of a mile - at the rear or foot of the Hills is the Protestant

Cemetery,’ 1870s. Author’s Collection.

The British photographer, David Griffith joined Lai Fong in 1878.31 His important role in the business, as well as its range of services, is apparent from an advertisement placed by Lai Fong in the Hongkong Telegraph on 1st October 1881:

|

Afong, photographer, has a larger collection of views |

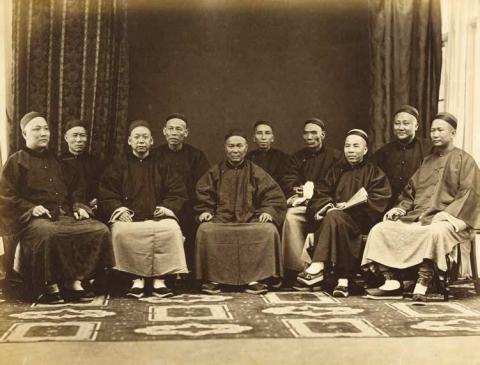

Fig. 6.20. Lai Fong (Afong Studio).‘A Group of all the different Compradores

employed at the European Hongs, in Hongkong’, 1870s.

The accompanying printed caption has the number ‘98’. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.21. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). Two compradors, 1870s.

The Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank comprador Lo Yewkee (Lo

Pak Sheung), shown on the right, represented the bank from

1865 until his death in 1877. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.22. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). ‘The late Compradore of

the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation named

Lo Yewkee.’, 1870s. The accompanying printed caption has

the number ‘630’. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.23. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). ‘No. 42. Native Actor and Actress’, 1870s.

The original number has been crossed through in pencil and the new number

'697’ has been substituted. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.24. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). ‘No. 34. Group of Chinese Actors and

Actresses’, 1870s.The original number has been crossed through in pencil

and the new number ‘691’ has been substituted. Author’s Collection.

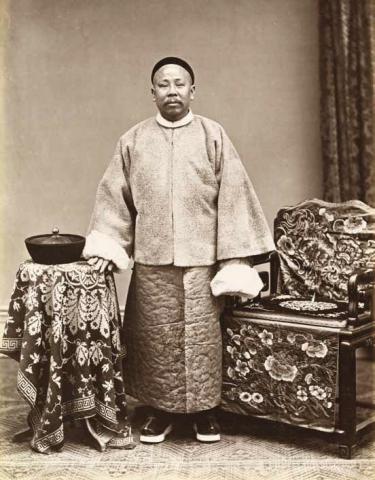

Fig. 6.25. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). ‘No. 627. – The one on the left is a

civil Mandarin of high rank named Chan Ting Chee, while that on the

right is Pang Yook the late Commander of Kowloon, a military’, 1870s.

Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.28. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). ‘Portrait of Japanese

Merchant [at Hong Kong],’ c.1873.Tom Burnett Collection.

Fig. 6.26. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). Chinese actors, 1870s. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.27. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). Mandarin’s wife, 1870s. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.29. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). ‘No. 43. “Chang” – the Chinese Giant.

The tallest man in China, he is seven feet eight inches in height’, 1870s.

Author’s Collection.

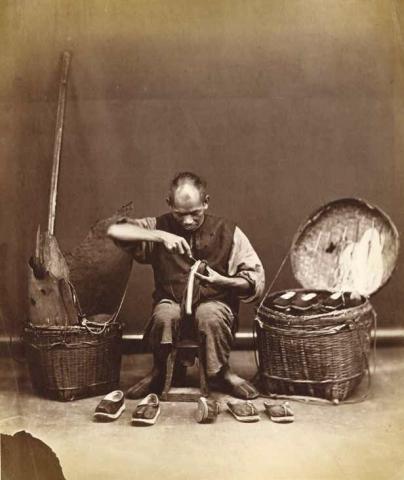

Fig. 6.30. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). Chinese barber, 1870s. A close

variant carte de visite is illustrated in Wue, Picturing Hong Kong, p. 123.

Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.31. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). A cobbler, 1870s. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.32. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). ‘No. 626. – A late Opium Merchant of

Hongkong who obtained the honorary distinction of the rank of a Mandarin

by purchase’, 1870s. The carpet, curtain and skirting board are the same

as those in the carte de visite portrait shown in fig. A56.The sitter is the

same as in fig. 6.33. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.33. Lai Fong (Afong Studio). ‘No. 78. A Hongkong Opium

Merchant in full costume. On the thumb of the left hand is a jade

stone ring, they use this to place the end of the arrow against when

firing with the bow’, 1870s.The sitter and studio setting are the same

as in fig. 6.32. Author’s Collection.

Lai’s business interests were not confined to photography. For example, on 1st October 1877 he and a Macau merchant named Choy Chew, jointly acquired for $19,000 a plot of land from a C. P. Chater known as Inland Lot 293A (Queen’s Road), which they sold for $55,000 on 24th August 1881.32 In partnership with Griffith, Lai invested in the London Aerated Waters Manufactory,Wellington Street, Hong Kong, in 1881.33 Also in 1881, the Hongkong Telegraph reported on 18th July:

We observe that the steamship Hainan has changed her American flag for a British one, having recently been purchased from Messrs. Russell & Co., by Mr. Afong, the well-known photographer of Queen’s road. The Hainan left yesterday for Hoihow, under the command of Captain Speechley, late Boarding Officer in the Harbour Master’s Department.

Lai Fong’s growing prosperity is evident from a report in the London & China Telegraph on 22nd November 1883 (p. 1033):

The commercial and industrial enterprise of the Chinese capitalists of Hong Kong has recently discovered a new field of action in the establishment of an engineering factory. Messrs. Hop Shing and Co., engineers, &c., Ness Iron Works,West Point, now announce themselves ready to undertake all orders entrusted to them in engineering, boiler making, iron and brass foundry works, &c. Mr. Afong, the enterprising photographer and shipowner, is, we are informed, the managing director of the new company, while the works are under the immediate superintendence of Mr. J. T. Waddell, an experienced engineer. Plenty of work is expected to be received by the engineer in charge, who has at present a staff of nearly sixty boiler makers, moulders, fitters, blacksmiths, &c., employed on the premises, and there appears to be every prospect of a busy and lucrative career before the new company.

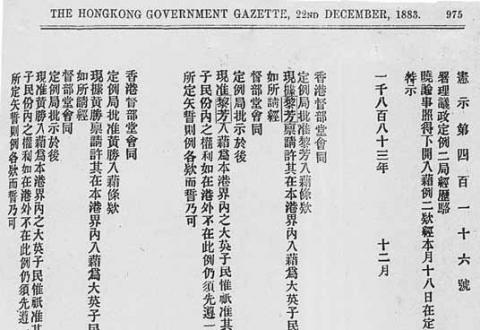

Fig. 6.34. Notice concerning the naturalisation of Lai Fong, Hongkong

Government Gazette, 22nd December 1883.

In 1883 Lai Fong applied to become a naturalised British subject. This received the assent of the Governor of Hong Kong, Sir George Bowen, on 28th December 1883 and was reported in the Hongkong Government Gazette on the following day:

No. 13 of 1883.

An Ordinance enacted by the Governor of Hongkong, with the advice of the Legislative Council thereof, for the naturalisation of Lai Fong.

(28th December, 1883).

Whereas Lai Fong has petitioned to be naturalised as a British subject within the limits of this Colony . . . he is hereby naturalised . . . and shall enjoy within this Colony, but not elsewhere, all the rights, advantages and privileges of a British subject, on his taking the oath of allegiance . . . .

Assented to by His Excellency the Governor, the 28th Day of December, 1883.

W. H. Marsh,

Colonial Secretary. 34

The Queen’s confirmation of this ordinance was officially announced in the Hongkong Government Gazette in April 1884.35

In 1883 the Afong studio was located at Lombard Street. Sometime in 1884 it moved to Queen’s Road, opposite the Hongkong Hotel. By early 1884 Griffith was no longer its manager and had set up his own studio in Hong Kong.36 An advertisement in the Hongkong Daily Press on 23rd December 1884 announced the appointment of another foreign assistant, Robert Douglas,37 and reveals that the studio’s photographs were by now also available from Kelly & Walsh, a bookselling firm with extensive operations throughout the Far East:

|

AFONG, PHOTOGRAPHER Begs to inform the Residents of Victoria and the STUDIO, QUEEN’S ROAD, |

In 1885 the studio moved again, this time to Ice House Lane, as listed in that year’s Chronicle & Directory for China, Japan, the Philippines &c. In 1886 it exhibited at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition, London, publicising its participation in the notice printed on the reverse of its portrait cards in use at this time. It is not known whether Lai Fong himself travelled to Britain to attend the exhibition: it may be significant that 1886 is the only year between 1882 and 1890 when Lai Fong’s name does not appear in the Hong Kong jury lists, possibly because of his absence abroad then.

Lai Fong’s advertisement in the Chronicle & Directory for China, Japan, the Philippines &c. for 1887 indicates the range of his stock and services:

|

AFONG, Than any other Establishment in the Empire of STUDIO, ICE HOUSE LANE, BEHIND NEW |

A similar advertisement was placed in the Chronicle & Directory for 1888. For 1889 it added: ‘New style of photograph in postage stamp form and size taken. Autotype printed photographs’.

In perhaps his last official engagement, Lai Fong was commissioned to provide the photographs to accompany the surveyor general’s report on the typhoon that struck Hong Kong on 29–30th May 1889.38 At around this time Lai’s financial position experienced a sudden decline, maybe because he had tried to expand his business operations too quickly.

Lai Fong died on 19th April 1890. The Hongkong Telegraph printed this notice on 21st April:

Old Afong, the photographer, died on Saturday night. He was seized with an apoplectic fit, and before he could get a negative remedy ready Death had “taken” him.

Another brief announcement of Lai Fong’s death appeared on the same day in the Hongkong Daily Press:

Mr. Afong, the well known photographer, died suddenly on Saturday evening from apoplexy. He was 51 years of age.

Lai Fong died intestate and his estate went into official administration. The appraised ‘value of effects’ was given as Hk$20,000.39 His businesses were left carrying losses and significant debt, but within a year they had been turned round by the skilful management of his daughter-in-law, Cheung Yuen Ming.40

Lai Fong combined a wonderful artistry in photography with exceptional marketing skills, flair and commercial acumen. Although his business affairs started to suffer towards the end of his life, his studio had for many years been the most successful in China. He will be remembered as one of the finest nineteenth-century photographers in the Far East.

A Note on Attribution

Lai Fong acquired the negatives and stock of many of the studios that failed, or ceased to operate, when their owners left China. Surviving albums from the Afong studio compiled before 1890 include, amongst others, photographs by Milton Miller, Dutton & Michaels, William Floyd and John Thomson – all mixed in with Lai Fong’s own work. It seems probable that the studio acquired a number of negatives and/or prints from these former studios. Not surprisingly, this makes the attribution of Lai Fong’s work problematic. In addition, the position is further complicated because William Floyd himself is known to have acquired and published the work of former studios such as Dutton & Michaels, Milton Miller and possibly Richard Shannon.41 Appendix 2 further discusses the attribution of Afong studio photographs and lists those that have been identified.

The Afong Studio after 1890

The Afong studio remained in business for many years after Lai Fong’s death.42 Administrative continuity was ensured by the retention of Hilario Antonio Rosario (Rozario) as managing clerk. Employed by Lai Fong since 1887, Rosario would remain with the studio until at least 1909.43 The Chronicle & Directory for China, Japan, the Philippines &c. for 1891 listed ‘A Fong Jr.’ as the photographer, who was most probably Lai Fong’s eldest son, Lai Yuet-chen (1871–1937).

The Afong studio placed a half-page advertisement in Kelly & Walsh’s Hand-book to Hongkong published in 1893:

|

AFONG, than any other Establishment in the Empire of STUDIO, ICE HOUSE ROAD. |

This advertisement is similar to that published by Lai Fong himself in the Chronicle & Directory for China, Japan, the Philippines &c. for 1887 (quoted above) and indicates that the studio continued to offer essentially the same services after Lai’s death as during his lifetime.

Interestingly, in the same year, 1893, David Griffith, Lai Fong’s former colleague and competitor, advertised in another guidebook,William Legge’s Guide to Hongkong:

|

GRIFFITH’S. New Views illustrating photographically the Island of VIEWS & GROUPS. D. K. GRIFFITH, |

Later in the 1890s several of the Afong studio’s photographs appeared in The Graphic, a popular illustrated newspaper published in Britain. They include Captain Von Hanneken by ‘A. Fong, Hong Kong’ (11th August 1894, p. 150); the Chinese warship Wei-Yuen and a fire at Canton (Guangzhou) ‘From Photographs by Afong, Hong Kong’ (20th October 1894, p.452); the unveiling of Queen Victoria’s jubilee statue at Hong Kong ‘From photographs by Mr. A. Fong, of Hong Kong’ (18th July 1896, p. 87); and a view of Wuchow (Wuzhou), newly opened as a treaty port, ‘From a photograph by Afong, Hong Kong’ (15th May 1897, p. 601).

In 1897 the Afong studio placed a three-page advertisement in Hurley’s Tourists’ Guide to Hongkong. Headed ‘A Fong Photographer, Ice House Street’, it promised ‘a more complete collection of Photo Views than any other establishment in the Far East’, as well as offering ‘developing, & printing for tourists’, ‘permanent enlargements & reproductions on paper, canvas and opal’, and ‘studio portraiture & out-door work’, ‘Everything up to date’. The second page printed a list of ‘A Fong’s Views of Hongkong, &c’, numbered 1–24, and the third, ‘A Fong’s Views of Canton, Peking, &c’, numbered 25–36 (Canton) and 37–48 (Peking), with the note that ‘The above views from [i.e. form] a representative series, but there are a great many more to select from including views of the Coast Ports’.46

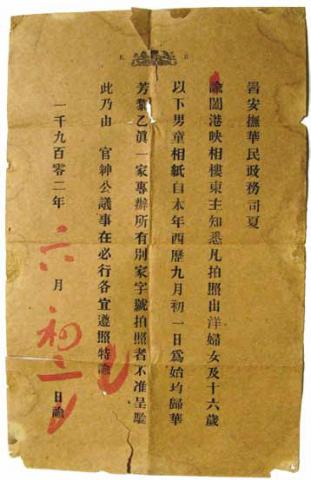

In 1898 the Hong Kong government jointly commissioned the Afong and Mee Cheung studios to produce photographs as part of the documentation of the extension of the colony into Kowloon and the New Territories.47 In 1902, the colonial government awarded the studio an exclusive contract to take passport photographs of women and children under sixteen.48

Fig. 6.35. Hong Kong Colonial Government Ordinance, 1902, awarding

the Afong Studio a contract to take passport photographs of women and

children. Courtesy of the Hong Kong Mantra School for Lay Buddhists,

Hong Kong.

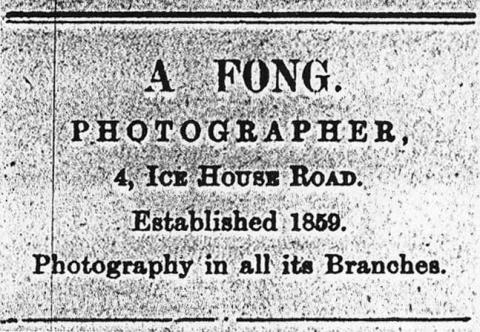

Fig. 6.36. Advertisement stating that the Afong studio was ‘Established 1859’,

South China Morning Post, 1st June 1904.

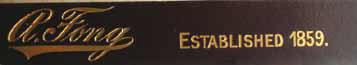

Fig. 6.37. Detail from the mount of a cabinet card with the imprint of the

Afong studio, ‘Established 1859’, c.1900.

The South China Directory for 1904 listed A Fong’s Photographic Studio, Ice House Road, A Fong, photographer, H. A. Rosario, clerk.49 It also included the studio’s advertisement, with the (probably mistaken) statement that it had been established since 1859:

A Fong, Photographer, Ice House Road, Hongkong (East side of Thomas’ Hotel leading up) Established 1859. Has a most complete collection of photographic views in the Far East. Developing and printing undertaken. Photography in all its branches.

Other advertisements and the studio’s imprints of this period similarly said ‘Established 1859’, as did Allister Macmillan’s Seaports of the Far East Illustrated, which was full of praise for the studio:

A. Fong, Photographer, 31, Queen’s Road, Central. Hong Kong’s best photographer is Mr. A. Fong, whose business has been established here since 1859. In his premises are to be seen artistic specimens of photography in all processes, together with beautiful miniatures and oil paintings. His studio is up-to-date with backgrounds and accessories. Developing and printing for amateurs are skilfully executed, and the prices charged are very moderate.

Mr. Fong has always in hand a large collection of views of Hong Kong, Canton, Macao and other China ports, and most of the illustrations in this section of our book are reproductions of his work.

Every visitor to the island whose requirements tend in the directions indicated should certainly visit Mr. Fong’s establishment. A staff of intelligent and courteous assistants are employed, and nothing is left undone to enhance the good reputation which the business enjoys.50

Despite such praise and its long established reputation, the Afong studio was not of course without serious competition. For example, Mee Cheung & Co. (with whom Afong had collaborated in 1898 in photographing the New Territories) undertook ‘all classes of work’, won medals at the St Louis Universal Exposition in 1904 and the Hongkong Exhibition in 1906, and received royal commendation for its photography of the visit of the Duke and Duchess of Connaught to Hong Kong. Based in Ice House Lane, it was described in 1908 as ‘one of the oldest photographic firms in the Colony’. Its manager:

Mr. W. Chong Kai, is a capable artist. The assistant manager, Mr. Y. Johnson, who has been with the firm since it was first started, has had experience in the United States. About thirty hands are employed at the head office, and a new depôt was opened at No. 8, Beaconsfield Arcade, chiefly for the sale of photographic stores for amateurs.51

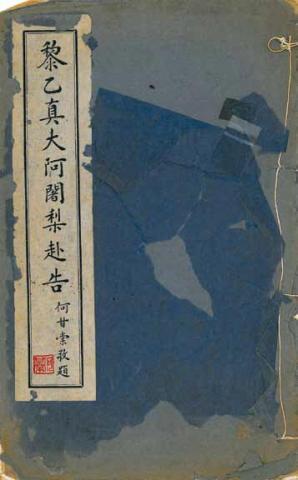

The death of Lai Yuet-chen 黎 乙 真, Lai Fong’s eldest son, on 1st March 1937 was announced in the South China Morning Post on 3rd March 1937 (p. 12):

MR. LAI YUET-CHEN – Veteran Photographer and Painter

The death has occurred after a week’s illness of Mr. Lai Yuet-chen, the proprietor of the Colony’s oldest Chinese photographic and portrait painting business, known as A. Fong, of D’Aguilar Street, which was opened for business some eighty years ago. Until he was attacked by a serious throat ailment, the late Mr. Lai was in excellent health despite his age of 67. He was for more than ten years a vegetarian and a devout Buddhist, and was for some years Chairman of the Kui Shi Lam Buddhist Association in Tai Hang.

It will be recalled that Mr. Lai Yuet-chen was one of the most energetic among those who organised the Chinese procession last year in connection with the late King George V’s Silver Jubilee. The deceased is survived by his wife. The funeral will take place this morning, leaving the residence in Tai Hang at 11.30 for the Yat Pit Ting in Kennedy Town.

And on 10th March 1937 the Overland China Mail reported:

Buddhist Philosopher Passes Away.

A deep sense of loss was occasioned in local Buddhist circles by the passing of a devout co-religionist and an old resident of the Colony in the person of Mr. Lai Yuenchan [sic], proprietor of A Fong, the photographers, at the age of 67 years. Mr. Lai began the study of Buddhism in its various branches in his teens and he was instrumental in the organisation of many Buddhist Societies in Hong Kong and the interior. When approaching the age of 50 years, he devoted himself to the study of the doctrines of the Mantra Sect, and perfected his studies in Japan under the instructions of the Reverend Konda. With the support of his friends, he succeeded in establishing a Mantra School, and took thousands of disciples, both upasakas and upasikas. As a philanthropist, he was one of the promoters of the Tung Sin Tong and the Keng Woo Hospital of Macao, and he also established several free vernacular schools at his own expense for the education of the poor.

The Chinese-language press, such as the Hua Zi Ri Bao (Chinese Mail) on 2nd March 1937, also reported Lai Yuetchen’s death.

Fig. 6.38. Anonymous. Portrait of Lai Yuet-chen, eldest son of Lai Fong,

c.1920, from his obituary, 1937. Courtesy of the Hong Kong Mantra School

for Lay Buddhists, Hong Kong.

Fig. 6.39. Obituary for Lai Yuet-chen, compiled and published by the Hong

Kong Mantra School for Lay Buddhists, Hong Kong, 1937. Courtesy of the

Hong Kong Mantra School for Lay Buddhists, Hong Kong.

The Kui Shi Lam Hong Kong Mantra School for Lay Buddhists, which Lai Yuet-chen founded, is still in existence. A number of records concerning its founder and his family are preserved in the school, including a printed obituary of Lai Yuet-chen, compiled soon after his death by his wife, Cheung Yuen Ming, and members of the school (this refers to his father, Lai Fong, using the alias Lai Chuk Tin). Cheung Yuen Ming (1872–1948) came from Macau (Aomen) and married him when she was seventeen. Their two children, a boy and a girl, both died young. Lai Yuet-chen’s younger brother, Lai Lap-yee 黎立儀, had two sons, Lai Bing-kwan 黎炳坤 and Lai Hon-leung 黎漢樑. Lai Fong’s death certificate shows the informant to be his son, Lai Hong 黎康. This could be an alias for Lai Yuet-chen or his brother Lai Lap-yee. Alternatively, it could mean that Lai Fong had three sons. Also preserved in the school is a photograph of Lai Yuet-chen’s parents – the photographer Lai Fong and his wife, Ho Shi.

Fig. 6.40. Anonymous. ‘The Portraits of the old boss Lai Chuk Tin [Lai Fong]

and his wife Ho Shi. Respectively Painted by Companions at Sheng Gang

[Hong Kong], A. Fong Photographer, inscribed by Ming Chu’ (captioned in

Chinese characters), 1880s. Two enlarged hand-tinted photographs mounted

in one frame (70 x 110 cm). Courtesy of the Hong Kong Mantra School for

Lay Buddhists, Hong Kong.

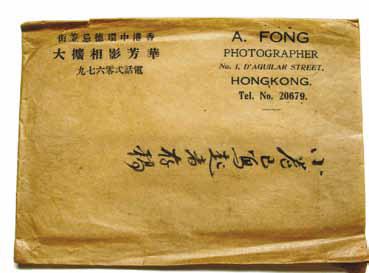

Fig. 6.41. Afong Studio envelope, c.1930. Courtesy of the Hong Kong

Mantra School for Lay Buddhists, Hong Kong.

The business continued under the ownership of Cheung Yuen Ming. The studio was listed in the 1941 edition of the Directory & Chronicle for China, Japan, Corea, Indo-China, etc. as ‘A. Fong’s Studio, Photographers – 1, D’Aguilar Street;Teleph. 20679’.52

Cheung Yuen Ming died, aged 76, on 9th January 1948. An obituary of her was published by the Hong Kong Mantra School for Lay Women Buddhists soon after, which, as we have seen, reveals how she turned round Lai Fong’s faltering business after his death in 1890. She bequeathed the bulk of her estate (an impressive Hk$ 177,500 at her death) to the Kui Shi Lam Hong Kong Mantra School for Women which she founded. In her will, dated 30th March 1938, she made some provisions for the studio and its employees: ‘I desire that my trustees shall carry on my business now carried on under the style or firm name of “A Fong”, Photographers at No. 1 D’Aguilar Street, Victoria, aforesaid, with discretion to increase or diminish the capital thereof ’. The trustees were also directed to retain the services of both Cheung Wai Hang and Lai Man Shan as they ‘have been associated with the said business since their childhood’. Permission was also given to her trustees to sell the business at any time they thought fit.53

It has not been possible to establish exactly when the Afong studio finally closed, suffice to say that the 1947 edition of the Hong Kong Year Book (in Chinese) lists an A. Fong Studio at an address in the New Territories, Hong Kong: 2/F, 1 Fuk Ting Street,Yuen Long. It does not appear in the 1948 edition, and so ends the story of one of the most successful and longest-lived photographic establishments in China, eighty or so years after its founder, Lai Fong, had established it as an independent studio.

Ye Chung

One of Lai Fong’s main competitors in Hong Kong was the Ye Chung studio. The nomenclature of this studio is confusing. It has been variously rendered also as Yi-chung, Yee Cheong and Yee Chun, but it is not clear whether these all refer to the same studio.

The origins of the studio were described in an article on pioneering Cantonese photographers published in a Chinese photographic journal in 1922, as translated by Edwin Lai:

The three gentlemen Zhou Senfeng, Zhang Laoqiu and Xie Fen . . . lived transiently in Hong Kong during the years of Xianfeng [1851–1861]. The three were partners in the oil painting business, and the name of their studio was Ye Chung. Because photography was related to painting, they coveted it. They put some money together and hired a Westerner at the Parade Ground to instruct them by writing down the technical procedures. At that time, the dry-plate process was not yet invented, and they learned wet-plate methods.

Having learned the techniques, they each raised two hundred yuan and switched their business to photography. Business was much better after a couple of years of operation. They closed the accounts and found each had made a profit of more than nine thousand yuan. They therefore decided to end their partnership so that they could make further progress. Zhou stayed in Hong Kong, Xie went to Fuzhou, and Zhang went back to the province [Guangdong]. Zhang opened a studio, which he named Ye Chung, on the southern bank of the river of the province. From the first year of [Emperor] Tongzhi [1862] to the final years of the Qing dynasty, the studio was still operating.54

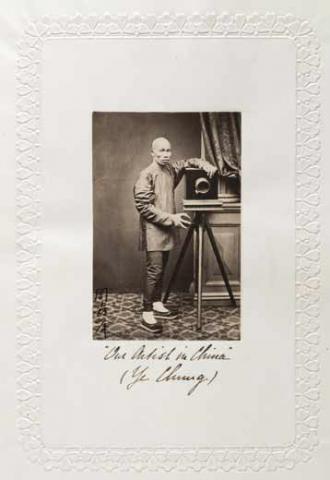

Fig. 6.42. Ye Chung. Portrait of Zhou Senfeng, proprietor of the Ye Chung

Studio, Hong Kong, 1870s. The photograph is signed in Chinese characters

by Zhou and the mount is captioned in English ‘Our Artist in China (Ye

Chung)’.This is the only known likeness of Zhou. Private Collection.

Another Ye Chung studio operated in Shanghai in the 1860s, although what the exact connection was with the three other studios above is not clear. A photographer known as Ye Chung operated in, or more likely passed through, Kiukiang (Jiujiang), from where the British merchant, Robert W. Little wrote on 25th October 1864 to his father, saying he was ‘sorry to see you are so disappointed with my portrait: I thought it a very fair one, but Kitty seems to think very poorly indeed of it. I will be done again by Mr.Ye-Chung soon’.55

In the author’s collection there is a carte de visite of a pet dog with the studio’s name and address, ‘Ye-Chung, Photographer, Portrait Painter, &c. No. 413 Queen’s Road, Hongkong’ printed on the reverse, which is also inscribed by hand, ‘Charley. Hongkong. March 10, 1864’ (figs. A126-7). An advertisement for ‘Yi-chung Photographer and Portrait Painter, &c.’ was published in the Hongkong Daily Press on 15th May 1866. In the listing of ‘Photographers’ in the China Directory for 1867 the studio appeared as ‘Yee Cheong’.56 The Hong Kong studio moved from 413 to 58 Queen’s Road sometime in the late 1860s. The 1868–1871 editions of the Chronicle & Directory for China, Japan, the Philippines &c. and the China Directory for 1874 list the studio at 58 Queen’s Road. By the mid 1870s it had moved to 68 Queen’s Road, the address printed on the backs of many of the studio’s cartes de visite from this period. It was still there in 1889.

Some doubt about all this remains, however, and there may well have been more than one Ye Chung studio operating concurrently in Hong Kong. The 1879 Chronicle & Directory for China, Japan, the Philippines &c. lists ‘Yee Chun’ as a portrait painter at 20 Wellington Street. In an advertisement in the Hongkong Daily Press on 1st April 1884 (p. 1), ‘Yee Cheong’ is referred to as a painter, rather than photographer, operating from 2 Wellington Street:

|

YEE CHEONG, SHIP, PICTURE, & PORTRAIT PAINTER. Terms Strictly Moderate. No. 2,Wellington Street, |

In the same issue the newspaper recommended (p. 2):

A visit to the studio of Mr. Yee Cheong, the painter, at the corner of Wyndham and Wellington Streets, will well repay the trouble. A large variety of Chinese craft, in all weathers, many river and country scenes, and large views of Hongkong, well executed, are to be seen. Mr.Yee Cheong is also a capital portrait painter.

The 1885 Chronicle & Directory for China, Japan, the Philippines &c. has the portrait painter Yee Cheong still at No. 2 Wellington Street. Yee Chun, a portrait painter at 56 Wellington Street, is also listed.

Finally, although the Ye Chung studio in Foochow was supposed to have opened in the early 1860s, the author has been unable to find any evidence of its existence earlier than about 1881. Its address, as printed on the reverse of a carte de visite portrait, was: ‘Yee Cheong. Photographer and Portrait Painter Chung Chow Island. Foochow’ (figs.A151-2). Further research is clearly required to establish this studio’s history with any degree of accuracy.

Pun Lun

Another major early studio in Hong Kong was known as Pun Lun. It advertised its services in the Hongkong Daily Press on 8th September 1864, shortly after its opening:

|

PUN LUN Queen’s Road, No. 58 Opposite the ORIENTAL Hongkong, |

Fig. 6.43. Pun Lun. Ornately decorated back of a typical cabinet card from

Pun Lun’s Hong Kong studio, c.1890.

As Chinese-owned studios tended to concentrate on studio portraiture, it is interesting to note here that Pun Lun stocked a range of landscape views for sale as well. The studio was still in operation in the early twentieth century, and throughout its existence remained a serious competitor to all of the Hong Kong-based studios.

The origins of the Pun Lun studio were described in an article on the beginnings of the photographic trade in Canton published in a Chinese photographic journal in 1922:

The gentleman Wen Dinan was a native Cantonese. His father owned a shop named Pun Lun in Guangzhou at Dasen Street, which dealt with textiles manufactured in Suzhou and Hangzhou. The shop had done a lot of trading with foreigners. On one occasion, an American who came to Canton via Hong Kong lodged at the shop. The American had a camera with him and was planning to photograph landscapes and scenes of the city. Dinan was fascinated by the medium and asked the American to teach him the craft. That was during the reign of Emperor Tongzhi [1862–74], a time when the dry plate had not been invented. Only wet plates and albumen papers were in use.57

At an earlier date the Pun Lun business had a portrait-painting studio in Hong Kong, as a British naval officer who visited the colony with HMS Tribune in 1857 recalled:

A naval surgeon wishing to send an oil-painting, enlarged from a photograph, of himself to his wife, photography being then in its infancy, applied to Pun-lun, one of the numerous tribe of portrait-painters which flourished at Hong Kong, rude, hard, uncompromising fidelity being the noticeable characteristic of their productions. When the portrait was finished the good doctor went to inspect, but being anything but satisfied with the result, exclaimed indignantly, “Thisy no number one, thisy no handsome facey,” to which old Pun-lun – dignified and in huge round spectacles – quietly retorted – “Sposy hansum facey no hab got, hansum facey how can do?”58

Further light is thrown on the history of the studio in a curious notice, published in the Hongkong Daily Press on 16th September 1865. It seems that the owner of the studio, Wan Chik-hing, left after an argument over money with Wan Leong-hoi, who may have been his brother:

NOTICE

THE PHOTOGRAPHICAL business in the upper Storey of Punlun No. 56 Queen’s Road, was carried on by Wan-chik-hing and Wan-leong-hoi from the 7th Moon of the 3rd year of Tungchi [August/September 1864] until the 7th Moon of this year, when on settling accounts, it was found that Wan-chik-hing has overspent, he is willing to give up his share of the above business, which will in future be carried on by Wanleong-hoy only, and whether the said business should be successful or failing, it shall be nothing to Wan-chikhing, and if Wan-chik-hing has or will incur any debts, it shall also be nothing to Wan-leung-hoi.

Hongkong,

14th September, 1865.

The photographic trade in Hong Kong was highly competitive and Pun Lun was prepared to adjust its prices accordingly, as in this advertisement placed in the Hongkong Daily Press on 21st October 1868:

|

GREAT REDUCTION. On and after the 20th of September, our Prices for PUN-LUN, No. 56, Queen’s Road Central, |

By 1882, the Hongkong Directory & Hong List advertised the price of Pun Lun’s cartes de visite as $2 per dozen. His cabinet pictures were $4 per dozen.

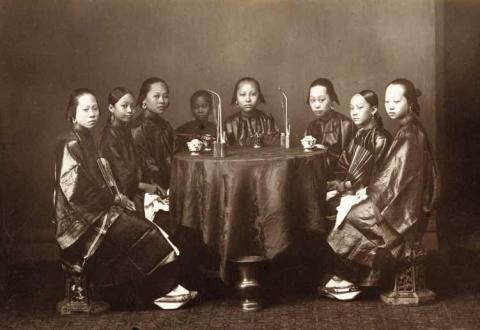

Fig. 6.44. Pun Lun. Group of Chinese women, 1870s. A number of

recognisable Pun Lun studio props are present in this picture.

Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.45. Pun Lun. ‘Two Mandarins’, 1870s.This image is also used as the

central photograph in the Pun Lun studio’s promotional collage (see fig. 3.1).

Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.46. Pun Lun. Blind musicians, 1870s. Author’s Collection.

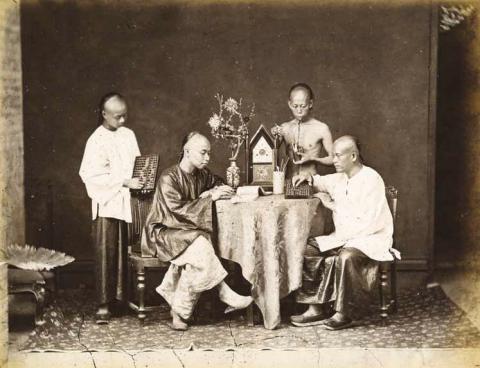

Fig. 6.47. Pun Lun. Chinese merchants, 1870s. Compare the

studio props with those shown in fig. A95. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.48. Pun Lun. Woman carrying a child on her back, 1870s.

Author’s Collection.

The success of the Pun Lun studio encouraged the formation of branches in Foochow (Fuzhou), Saigon and Singapore. The names of the photographers in these various studios are unknown. The Hong Kong studio was located at various addresses in Queen’s Road during at least the first twenty-five years of its existence. It survived a serious fire, which destroyed the premises in June 1876, and was still operating at the beginning of the twentieth century.59 There is little doubt that the Pun Lun studio, at least in Hong Kong, was commercially successful. Its longevity was impressive, and the studio’s portrait work was in high demand, judging by the relatively large number of surviving cartes de visite bearing its imprint. Besides studio portraiture, it also produced an attractive series of genre portraits of Chinese types. Only a few of the studio’s advertised south China and treaty-port views are known: the negatives were perhaps destroyed in the Hong Kong studio fire of 1876.

Pun Lun carte de visite photographs invariably had the studio’s address printed on the back, but tracing its movements can be difficult. The following list (which does not claim to be exhaustive) of the studio’s various addresses in Hong Kong as advertised in the local press and directories may, therefore, be helpful in dating its cartes de visite:

- 58 Queen’s Road. Hongkong Daily Press, 12th September 1864.

- 56 Queen’s Road. Hongkong Daily Press, 16th September 1865.

- 56 Queen’s Road Central. Hongkong Daily Press, 21st October 1868.

- 59 Queen’s Road Central. Chronicle & Directory for China, Japan, the Philippines &c., 1868 (‘59’ is possibly a misprint for 56).

- 56 Queen’s Road Central. Chronicle & Directory, 1869–1879.

- 52A Queen’s Road Central. Chronicle & Directory, 1880–1881.

- 52A Queen’s Road Central. Hongkong Directory & Hong List, 1882.

- 56 Queen’s Road Central. Chronicle & Directory, 1885.

- 56 Queen’s Road Central. Hongkong Daily Press, 1st January 1887.

- 76 Queen’s Road Central. Hongkong Directory & Hong List, 1889.

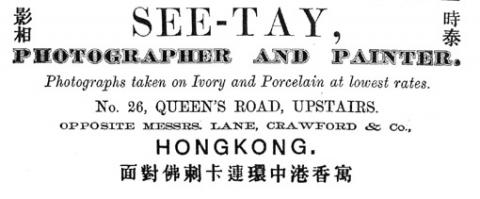

Liang Shitai (See Tay) fl. 1870s–1880s

One of the more famous photographers to come out of Hong Kong was Liang Shitai, or See Tay as he generally styled himself and as he was known in English. He seems to have first established himself in the colony in the early 1870s. In 1876, he relocated to Shanghai, before settling in Tientsin (Tianjin) in 1880, where he found favour amongst the ruling elite and was able to photograph prominent figures in the late-Qing dynasty.

As with Lai Fong (Afong), Liang named his studio after himself. His earliest known advertisement appeared in Hong Kong’s Daily Advertiser on 2nd October 1871:

|

SEE-TAY, |

Examples of Liang’s work in Hong Kong are rare. A carte de visite by him of a Hong Kong porter is known.60 Liang moved to Shanghai in 1876, possibly because of the increasing competition in Hong Kong or the economic depression which was impacting severely on business.

Fig. 6.49. Liang Shitai (See Tay). Studio advertisement from the China

Directory, 1873.

Hing Qua John & Co.

It is not clear when the Hing Qua John & Co. studio first opened in Hong Kong, or how long it was located there. Early 1860s cartes de visite exist, showing addresses at ‘No. 20 Praya, Hongkong (Next to Messrs. J. Stürje & Co)’, or ‘84 Praya, Hongkong’. It seems that the studio was more active in Shanghai, where it traded from 247 Canton Road. A carte de visite with this address in the collection of Serge Kakou has the date January 1864 written on the back.

Kai Sack

Currently, the earliest known definite date for a Chinese commercial studio in Hong Kong is 4th April 1864, the date of an advertisement for the Kai Sack studio. It was published in the Hongkong Daily Press on 6th April 1864:

|

NOTICE The undersigned having been many years in California KAI-SACK |

It is not known for how long Kai Sack was in business. On 21st June 1865 the Hongkong Daily Press printed a notice in which Kai Sack offered a reward of twenty dollars for the return of two stereoscopic lenses marked ‘John Jacob, October 15th 1861 NY’.61 There is a carte de visite in the collection of the Getty Research Institute which has the year 1868 written on the back. However, this date should be treated with some caution since it could simply represent when the photograph was acquired, not necessarily when it was taken. The printed address shows 109 Queen’s Road, Hongkong, but adds a second studio at 34 Rua de St Agostinho, Macau (Aomen). Portuguese-language newspapers might yield more information on Kai Sack’s business in Macau.

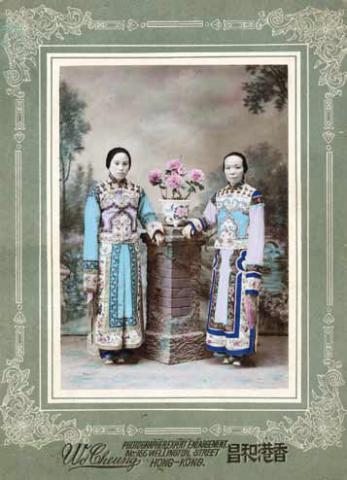

Wo Cheong (Cheung)

The studio of Wo Cheong (Cheung), photographer, daguerreotype copyist, and ship and portrait painter, operated until as late as 1894.62 It is first listed in the 1879 edition of the Chronicle & Directory for China, Japan, the Philippines &c. at 108 Queen’s Road Central where it was based until at least 1885. It later moved to 166 Wellington Street, which is the address printed on the mounts of a number of attractively hand-tinted silver print photographs of entertainers.

Fig. 6.50. Wo Cheong (Cheung). Actors, c.1890. Hand-tinted

gelatin silver print photograph. Author’s Collection.

Fig. 6.51. Wo Cheong (Cheung). Two Chinese actors, c.1890.

Hand-tinted silver print photograph. Author’s Collection.

Other Chinese Studios in Hong Kong

There is little to say about the many other studios whose names have come down to us through listings in the trade directories and newspaper advertisements of the 1860s and 1870s. In some cases, their names only appear in printed form on the mounts of surviving carte de visite portraits. The majority seem to have earned their living as painters and portrait photographers. It seems only a minority offered photographic views. However, as research into the early Chinese photographers is still at an early stage, it is to be expected that more information about some of those named, or indeed new names altogether, will emerge over time. At present, from listings in contemporary trade directories, newspaper advertisements, and cartes de visite with studio names printed on their mounts, the following studios active in Hong Kong during the 1860s and 1870s may be identified.

Cheong Heng at 66 Queen’s Road, in partnership with Wing Chong c.1869–1874 (shown on the reverse of several cartes de visite).

Choi Fung at 32 Queen’s Road Central, listed in the 1877 Chronicle & Directory for China, Japan, the Philippines &c.

Hang Chung, known only from a carte de visite with no studio address.

Hing Cheong & Co., at 66 Queen’s Road c.1868–1874.

How Wa, trading as Apong & Co. was listed at 31 Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong in the 1878 and 1879 Chronicle & Directory, in which it was advertised that the studio also offered views of Canton.

Fig. 6.52. Apong & Co. (How Wa). Studio advertisement from the Chronicle

& Directory for China, Japan, the Philippines &c., 1878.

Hung Cheong Shing listed in the 1879, 1880 and 1881 Chronicle & Directory at 32 Queen’s Road Central, in 1885 at 75 Queen’s Road Central, and still active in 1887.63

Fig. 6.53. Hung Cheong Shing. Studio advertisement from the Chronicle &

Directory for China, Japan, the Philippines &c., 1879.

Kai Shik, listed in the 1871 Chronicle & Directory at 60 Queen’s Road Central, who was possibly connected to Kai Sack.

Kam Cheong, recorded by Clark Worswick as active in the 1870s.

King Fong at 32 Queen’s Road, known from an 1870s carte de visite.

Kwong Chu Low, listed in the 1879 Chronicle & Directory at 84 Queen’s Road Central.

Lai Sang, listed in the 1875–1878 Chronicle & Directory at 70 Queen’s Road and still in operation in the 1880s.64

Lai Sung, at 419 Queen’s Road, is known only from a carte de visite view, in the author’s collection, of the USS Oneida, a ship with the Asiatic Squadron from 1867 until 1870, when she sank at Yokohama. Quite possibly the same as Lai Sang since both studios bear the same Chinese characters.

Mun Hing is listed in the 1868–1871 editions of the Chronicle & Directory at 32 Queen’s Road. It continued until 1889.65

Nam Ching is listed in the Chronicle & Directory at 26 Queen’s Road (1868–1871) and at 84 Queen’s Road (1875–1878). The studio continued until the 1890s.66 Nam Ching is possibly the same studio as Nam Ting at 60 Queen’s Road, shown next to William Floyd’s studio in a photograph by Floyd of c.1868.67

Nga Chan (1870s–1880s) appears in the Chronicle & Directory at 60 Queen’s Road Central (1878–1879), at 80 Queen’s Road Central (1880) and at 90 Queen’s Road Central (1885). The studio continued until 1887.68 The back of a carte de visite in the Getty Research Institute collection has the studio’s name printed as N’Gha, at the 60 Queen’s Road Central address.

Seng Yuen at 94 Queen’s Road, known from a carte de visite of c.1880.

Shun Me Wo, listed in the 1876 Chronicle & Directory at 54 Queen’s Road Central.

Tin Sing at 124 Queen’s Road, c.1870, possibly connected with Ting Shing, who was a partner in the Canton (Guangzhou) studio of Dutton & Michaels, 1863–1864.69

Tou Shing (To Shing), listed in the 1875, 1876, 1878 and 1879 Chronicle & Directory at 6 Wellington Street and in 1880 and 1881 at 40 Stanley Street.

Tun Wo, listed in the 1871 Chronicle & Directory at 62 Queen’s Road Central.

Wing Chong, listed in the 1875, 1876, 1878 and 1879 Chronicle & Directory at 66 Queen’s Road Central and in 1880 and 1881 at 84, at 58 in the Hongkong Directory for 1882, and at 74 in the 1885 Chronicle & Directory.

Ya Chan, listed in the 1875, 1876 and 1877 Chronicle & Directory at 60 Queen’s Road Central.

Yat Sing, listed in the 1868, 1869, 1870 and 1871 Chronicle & Directory at 28 Praya and in business until 1874.70

Yau Shing, listed in the 1875, 1876, 1877, 1878 and 1879 Chronicle & Directory at 58 Queen’s Road Central and active until the late 1880s.71

Yuet Cheong, or Chong, listed in the 1875, 1876 and 1877 Chronicle & Directory at 62 Queen’s Road Central.

Lastly, the studio of Ating, portrait photographer and painter, is described by John Thomson,72 and another photographic establishment, Toong Shing, is known because of its conviction for dealing in indecent pictures, as reported in the Daily Advertiser on 11th September 1872:

The master of the Toong Shing photographer’s shop, No. 197 Queen’s Road Central, was summoned by P.C. Bond for having exposed indecent pictures for sale. His Worship fined the defendant $50: the pictures seized, 50 in number, were destroyed.73

References:

- For a contemporary guide, including an account of Hong Kong’s early years as a British colony, see N. B. Dennys, ed., The Treaty Ports of China and Japan. A Complete Guide to the Open Ports of those Countries, together with Peking,Yedo, Hongkong and Macao, 1867, pp. 1–115. For further background and photography, see Cécile Léon Art Projects, ed., First Photographs of Hong Kong, 1858–1875, 2010; Roberta Wue, Joanna Waley-Cohen and Edward K. Lai, Picturing Hong Kong: Photography 1855–1910, 1997.

- A. B. Freeman-Mitford, The Attaché at Peking, 1900, p. 5.

- Dennys, Treaty Ports, p. [vi]. See also Wue, Picturing Hong Kong, pp. 20–3.

- Christopher Munn, Anglo-China: Chinese People and British Rule in Hong Kong, 1841–1880, 2009, p. 346. The Hong Kong police force was, however, neither particularly effective nor well run at this time.

- John Thomson, ‘Hong-Kong Photographers’, British Journal of Photography, vol. 19, no. 656, 29th November 1872, p. 569. This article is reprinted as Appendix 3 below.

- Jens Jäger, ‘Photography: A Means of Surveillance? Judicial Photography, 1850 to 1900’, Crime, Histoire & Sociétés / Crime, History & Societies, vol. 5, no. 1, 2001, p. 28.

- Fok Kai-cheong, ‘Private Chinese Business Letters and the Study of Hong Kong History – A Preliminary Report’, in Collected Essays on Various Historical Materials for Hong Kong Studies, ed. Joseph P. Ting and Susanna L. K. Siu, 1990, p. 16 (quoting Bowen from Hong Kong Legislative Council Sessional Papers, 1883, p. 207).

- Bennett, History 1842–1860, pp. 11, 15–19, 23–4, 163–9. For Western studios after 1860, see Bennett, Western Photographers 1861–1879, pp. 1–30.

- For export trade painting and the early Chinese photographers, see Wue, Picturing Hong Kong, pp. 34, 54–5.

- Afong was the name used by Lai Fong in his studio’s advertisements, directory listings, labels on photographs and albums, and so forth. Hong Kong administrative records (in English) use his family name (Lai) but can render his given name as ‘Afong’ or ‘Fong’. See, e.g., the jury lists printed in the Hongkong Government Gazette: vol. 28, no. 8, 25th February 1882, ‘Lai A-fong, Photographer, Queen’s Road’ (p. 206); vol. 29, no. 11, 3rd March 1883, ‘Lai Afong, Photographer, Queen’s Road Central’ (p. 162); vol. 33, no. 8, 19th February 1887, ‘Lai Fong, Photographer, Ice House Lane’ (p. 172). The Gazette uses ‘Lai Fong’ in the announcements of his naturalisation, vol. 29, no. 61, 1883 (p. 982) and vol. 30, no. 25, 26th April 1884 (p. 332), and in its Calendar of Probates and Administrations, vol. 37, no. 20, 2nd May 1891 (p. 358). Lai Fong 黎 芳 is the name used on his death certificate. ‘A’ (sometimes spelt ‘Ah’) was an informal prefix commonly used in South China with a person’s first (given) name. It frequently confused Westerners and can often mean that transliterated names have more than one form in English: see Yong Chen, Chinese San Francisco, 1850–1943: A Trans-Pacific Community, 2000, pp. 53, 116, 280 (n.143). It was also common for Chinese to use one or more aliases. Lai Fong was referred to as Lai Chuk Tin in his son’s own obituary (see below), and also when appearing as a plaintiff in a court case ‘Lai Chuk Tin (al) Lai Fong v.Tsow Yune’, reported in the Hongkong Daily Press, 14th October 1885 (Carl Smith Collection, Public Records Office of Hong Kong, 21049). See also the caption to Lai Fong’s portrait in fig. 6.40, which again renders his name as Lai Chuk Tin.

- John Thomson, The Straits of Malacca, Indo-China and China or Ten Years’ Travels, Adventures and Residence Abroad, 1875, pp. 188–9.

- Obituary of his son, Lai Yuet-chen 黎 乙 真, in the records of the Kui Shi Lam Hong Kong Mantra School for Lay Buddhists.

- E.g., its advertisement in the South China Directory for 1904 and Allister Macmillan, Seaports of the Far East Illustrated, 1907, p. 67 (both quoted below).

- Bennett, Western Photographers 1861–1879, pp. 4–5, 8. Silveira continued to work at the studio after its acquisition by Floyd.

- National Galleries of Scotland, PGPR 871.1. From the collection of Peter Fletcher Riddell (1918–1985). The album’s earlier provenance is not known.

- Bonhams, Travel & Photography, London, 4th December 2012, lot 332, illustrating this image, p. 71. The album was compiled c.1868–1871 and is well captioned in a uniform contemporary hand. The majority of its photographs are of China, among them images by William Floyd and Milton Miller, but it also includes some of Korea by Felice Beato and a few of Singapore and India.

- Wue, Picturing Hong Kong, p. 56.

- For Floyd and Thomson in Hong Kong, see Bennett, Western Photographers 1861–1879, pp. 8–18, 216–19, 222–7. Lai Fong advertised his raffle in the China Mail, 11th December 1871: see Wue, Picturing Hong Kong, p. 56.

- Bennett, Western Photographers 1861–1879, pp. 18, 22–3.

- Bennett, Western Photographers 1861–1879, pp. 22, 271–2.

- Notice in Hongkong Daily Press, 6th December 1872.

- Thomson, ‘Hong-Kong Photographers’, p. 569.

- E. J. Eitel, Europe in China:The History of Hongkong from the Beginning to the Year 1882, 1895, p. 514.

- An album of 35 views of the typhoon, with the Afong studio label, is in the Serge Kakou collection. An album of 47 views attributed to Lai Fong, with printed caption slips on their mounts and a printed descriptive introduction, ‘The Typhoon of September, 1874’, pasted on the front endpaper, is in the British Library (India Office collections, Photo 337/2). Lai Fong’s competitor,William Floyd published a separate series of photographs of the disaster; an album of 22 of these is in the University of Michigan Library (DS796 H7 F6). For the photography of the typhoon, see also Filip Suchomel and Marcela Suchomelová, Perception and Image of China in Early Photographs, 2011, pp. 24, 55, 174–9. For Floyd, see Bennett, Western Photographers 1861–1879, p. 7–18.

- Illustrated in Suchomel and Suchomelová, Perception and Image of China, p.54.

- Thomson, Straits of Malacca, p. 189.

- D. K. Griffith, ‘Pen-And-Ink Sketch of a London Studio’, Photographic News, vol. 19, no. 899, 26th November 1875, p. 565, a whimsical piece that purports to describe a visit with Lai Fong to a fashionable photographic studio in London’s West End.

- A group of Western visitors were in the vicinity at about the same time, but, if they encountered Lai Fong, there is no mention in the published narrative: Herbert J. Allen, ‘Notes of a Journey through Formosa from Tamsui to Taiwanfu’, Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society, vol. 21, 1877, pp. 258–66.

- William Henry Lentz (c.1845–?), born in Baltimore, is recorded as working as a photographer in San Francisco and Petaluma, California, in the 1860s–1870s, by Peter E. Palmquist and Thomas R. Kailbourn, Pioneer Photographers of the Far West: A Biographical Dictionary 1840–1865, 2000, p. 364.

- As described by his grandson, James Pope-Hennessy, Verandah: Some Episodes in the Crown Colonies 1867–1889, 1964, p. 211 (Lai Fong’s portrait of Sir John Pope Hennessy is illustrated on plate facing p. 208).

- Wue, Picturing Hong Kong, p. 56 (n.40), citing Afong’s advertisement in the China Mail, 11th July 1878. Griffith’s occupation and address is given as ‘Photographer, A Fong, Queen’s Road’ in the 1879 jury list, Hongkong Government Gazette, vol. 25, no. 9, 5th March 1879, p. 110.

- Carl Smith Collection, Public Records Office of Hong Kong, Memorials 3708, 10261. The transaction was recorded using the name Lai Fong.

- Bennett, Western Photographers 1861–1879, pp. 271–2;Wue, Picturing Hong Kong, p. 37 (citing the 1881 Chronicle & Directory for China, Japan, Philippines etc., p. 216). Griffith was advertising this venture in his own name in 1882 and opened his own studio in Hong Kong in 1884.

- Hongkong Government Gazette, vol. 29, no. 61, 29th December 1883, p.982. The bill for the ordinance was read for the first time in the Legislative Council on 18th December, as notified in the Hongkong Government Gazette Extraordinary, vol. 29, no. 59, 20th December 1883, p. 947.

- Hongkong Government Gazette, vol. 30, no. 25, 26th April 1884, p. 332.

- Bennett, Western Photographers 1861–1879, p. 272. The last known advertisement by Griffith, then at Duddell St, Hong Kong, is in R. C. Hurley, The Tourists’ Guide to Canton, the West River and Macao, 1895, p. xxvii. Under ‘Griffith’s Views of Hongkong’, this lists 24 views, noting that they ‘form a representative series, but there are a great many more to select from, including views of the some of the Coast Ports’.

- Presumably the Douglas of Robert Douglas & Co., commercial photographers in Hong Kong in the mid 1890s. See John Falconer, From Bombay to Shanghai, 1994, p. 98.

- Wue, Picturing Hong Kong, p. 44.

- Hongkong Government Gazette, vol. 37, no. 20, 2nd May 1891, Calendar of Probates and Administrations for 1890, p. 358.

- See her obituary (1948), records of the Hong Kong Mantra School for Lay Buddhists.

- See also Bennett, Western Photographers 1861–1879, pp. 29–30, and Clark Worswick, Imperial China: Photographs 1850–1912, 1978, pp. 139–42.

- Other late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century studios with similar names but probably unconnected to Lai Fong’s are known from trade directories or credits printed on the mounts of their photographs. These include: Ah-Fong Photographer Wei Hai Wei; Lai Fong 565 Nanking Road Shanghai; and A-Fong 6 Shao Tai Ping Street,Tel. No. 362. Chefoo, N. China. For the early twentieth-century Ah Fong studio in Weihaiwei, which was responsible for some remarkable pictures of Qufu and Duke Kong, the descendant of Confucius (kongzi), and its possible (if unlikely) connection with the Afong studio in Hong Kong, see Sara Stevenson, ‘The Empire Looks Back: Subverting the Imperial Gaze’, History of Photography, vol. 35, no. 2, May 2011, pp. 147–9.

- Hongkong Daily Press, 8th February 1887; Directory & Chronicle for China, Japan, the Philippines &c., 1909.

- Kelly & Walsh Ltd, A Hand-book to Hongkong. Being a Popular Guide to the Various Places of Interest in the Colony, for the Use of Tourists, 1893, advertisement section, p. [15]. In their advertisement, Kelly & Walsh said that they sold photographs at studio prices (p. [1]).

- William Legge, A Guide to Hongkong with Some Remarks upon Macao and Canton, [1893], advertisement section, p. 39. Legge’s itinerary says in Ice House Lane, ‘some 50 yards up from Queen’s Road, is Mr. Griffith’s photographic studio, where the tourist may have himself taken as he appeared in Hongkong, and where he will find a collection of views of the Island from which to select such souvenirs of his visit as most please him’ (pp. 25–6).

- R. C. Hurley, The Tourists’ Guide to Hongkong with Short Trips to the Mainland of China, 1897, advertisements, pp. xxxiv–xxxvi (these pages appear after p. 75 of the text in the British Library copy). The only other photographer to advertise in Hurley’s guide was A. Farsari & Co., of Yokohama, offering the ‘best photographic Views and Costumes of Japan’ (p. xli). Hurley was himself a photographer and remarked in the guide’s introduction that ‘For the Amateur photographer subjects are endless’. He lived in Hong Kong for many years: the caption to his portrait in his Picturesque Hongkong, 1925, states that he ‘Arrived in Hongkong 14th March, 1879’. His Tourists’ Guide to Canton, 1895, is illustrated from negatives of his photographs and one of the advertisements names him as lessee and manager of the Shameen Hotel, Canton (p. xxix). Falconer, Bombay to Shanghai, p. 100, records two series of photographs by Hurley, Sixty Diamond Jubilee Photographs of Hongkong and Sixty Pictures of Canton, produced in 1897 and 1899 respectively.

- Wue, Picturing Hong Kong, pp. 44–5.

- Official printed notice in the records of the Hong Kong Mantra School for Lay Buddhists.

- Similar entries appeared in the 1905 and 1906 editions, and also in the 1904 Directory & Chronicle for China, Japan, the Philippines &c. The 1909 Directory & Chronicle lists the Afong Photo Studio, 31 Queen’s Road Central above Watkins’ Dispensary, A Fong photographer, H. A. Rosario, managing clerk.

- Allister Macmillan, Seaports of the Far East Illustrated, 1907, p. 67. The Hong Kong section, which includes A Fong’s photographs, comprises pp. 13–86; the title-page illustration, ‘Hong Kong – Looking East’, is also credited to ‘A. Fong’. A Fong’s photographs are found in the 1926 edition, but the studio itself is not described in the text. The photographs are all reproduced as half tones.

- Arnold Wright, ed., Twentieth Century Impressions of Hongkong, Shanghai, and other Treaty Ports of China, 1908, p. 234 (with an illustration of the shop’s facade and portraits of W. Chong Kai and Y. Johnson, apparently a Chinese- American). Mee Cheung advertised in R. C. Hurley’s Handbook to the British Crown Colony of Hongkong, 1920.

- See also Worswick, Imperial China, p. 149 (n.29).

- Will, dated 30th March 1938 (no. 86/49), Supreme Court of Hong Kong and Probate Jurisdiction; probate record 5th April 1948 (no. 369 of 1949), Public Records Office of Hong Kong.

- Deng Zhaochu, ‘Guangzhou sheyingjie de kaishanzu’, Sheying zazhi, no. 2, 1922, as translated and quoted by Edwin K. Lai, ‘The History of the Camera Obscura and Early Photography in China’, in Brush & Shutter: Early Photography in China, ed. Jeffrey W. Cody and Frances Terpak, 2011, p. 27.

- Little family papers (private collection). With thanks to Robert Bickers for this reference.

- Wue, Picturing Hong Kong, p. 54 (n.30).

- ‘Guangzhou sheyingjie de qianjue’, Sheying zazhi, no. 2, 1922, as translated and quoted by Lai, ‘History of the Camera Obscura’, pp. 26–7.

- Francis Martin Norman, “Martello Tower” in China and the Pacific in H.M.S. “Tribune” 1856–60, 1902, pp. 92–3.

- North China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette, 17th June 1876, p. 591; American Stereoscopic Co., ‘A Street in Hong Kong, China. Copyright 1901 by R.Y.Young’, stereocard showing the studio’s signboard over its premises (see fig. 3.4).

- Wue, Picturing Hong Kong, plate 48 (p. 115).

- Palmquist and Kailbourn, Pioneer Photographers of the Far West, p. 472; Wue, Picturing Hong Kong, pp. 53–4.

- Falconer, Bombay to Shanghai, p. 107.

- Falconer, Bombay to Shanghai, p. 100.