19th-century Hong Kong in engravings

Primary tabs

Engravings in the illustrated newspapers were the first view most British people had of Hong Kong in the 1800s. Here is a small set I bought last year, starting with one from the weekly "Illustrated London News" (ILN).

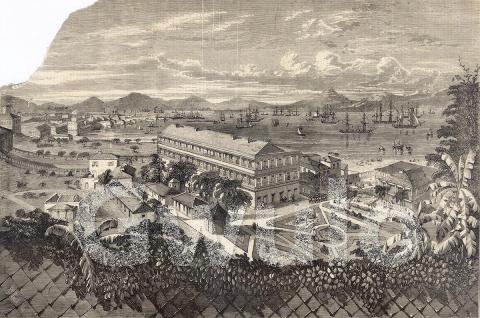

Dec 27, 1856 - The Illustrated London News

THE HARBOUR OF HONG KONG - FROM AN ORIGINAL SKETCH

It's quite random whether or not we get to see the text that originally accompanied the illustration. In many cases the engraving was cut out of the newspaper without any of the text, but sometimes you get the whole page, text and all. In this case we're lucky as although the text was on a separate page, whoever cut out the engraving also cut out the text and kept them together:

HONG-KONG.

We have to thank a Correspondent for the clever sketch of this new Colony, engraved in Supplement, page 662. The view shows the officers’ quarters, the harbour and town of Victoria, and the mainland; which is only a mile distant from the island.

Hong-Kong is governed by a Governor and Council. The Governor is also superintendent of trade, and the Council make laws for the island, subject to revision by the Colonial Secretary and the Queen in Council. In their time the Council have made some curious laws: such as those for punishing members of the Triad Society, who violated the laws of China; and those for registering all the people. Hong-Kong is the seat of all her Majesty’s Courts in the Chinese Sea, and all her military power and authority. On the south side of the island is the chief town, Victoria; and on the north side is the town of Stanley, named after the present Earl of Derby when he was Lord Stanley, and held the seals of the Colonial Office. There is a good road connecting them. Though. Hong-Kong is chiefly to be regarded as a military or governing station, it is a free port, and carries on a considerable transfer trade. The export from it to England is nothing, at least it is not distinguished from the general exports from China — the ships which stop there homeward-bound having obtained their cargoes in Canton, Amoy, or Shanghae. The imports of British produce and manufacture consist of slops, copper, cottons, cotton-yarn, linens, woollens, &c., to the value, in 1851, of £632,399 ; and, in 1855, of £389,265 : the decline in the trade being the consequence of the disturbed state of China. Hong-Kong costs the nation a handsome sum :—in 1851-52, £113,782; in 1853-51—the last return we have seen—£72,166; or not much less, one year with another, than £100,000 annually. Moreover, a yearly revenue is levied on the people by taxation of about £23,000.

In Hong-Kong a Government gazette is published, and there is at least one newspaper, the China Mail, which serves to diffuse valuable information concerning China in Europe, and probably, also, helps to diffuse information concerning Europe, in a very limited degree, amongst the Chinese. Hong-Kong has sometimes been a place of refuge for the persecuted on the mainland, and, with its toleration and justice, is always, before the eyes of the Chinese, presenting an example of the newest European civilisation. From us they have learned something of steam, and, probably, have seen a telegraph. Hong-Kong is in constant communication with England, and the mails are now transmitted backwards and forwards in about forty days.

As mentioned, the image started life as a sketch of Murray House and the harbour beyond. An engraver working for the ILN took the sketch and reproduced it on a wooden block, which was used to print the image shown above. A possible clue to the original artist's identity is a signature in the bottom left corner, though I'm not 100% clear if it is the signature of the artist or the engraver.

Next are a pair of engravings, separated by notes about the scenes. These were also copied from sketches.

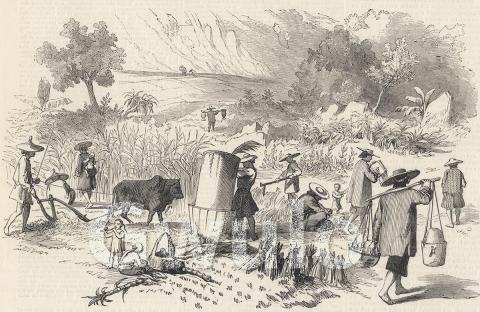

Jan 16, 1858 - The Illustrated London News

CHINESE HARVEST, HONG KONG

SKETCHES IN CHINA.

(From our Special Artist and Correspondent)

On the 1st of November I took a walk with a friend into the interior of Hong-Kong, and saw the process of rice-harvesting, beneath a bright, hot sun, the entire village population hard at work getting in the second crop of paddy. The principal part of the labourers are women, owing probably to the fact of the men being generally engaged in fishing. The paddy rice grows to a height of about two feet six inches. The fields are little patches of about fifty paces, on account of the unevenness of the ground. The rice is thrashed out of doors: first, in a tub with a screen, by a man, who takes a bunch in his two hands to strike the ears against the edge of a tub, and then gives the rice again to be threshed on a floor made hard with chunam, the Chinese asphalt. Ploughing is here done with a very primitive plough and a wonderfully small bullock, as the ground is soft and does not contain a single pebble. This is very well. After being harrowed it may receive a crop of sweet potatoes, or ground nuts. The women work with children on their backs. No one appears too young to take a part in the work. In the next fields are sugar-canes.

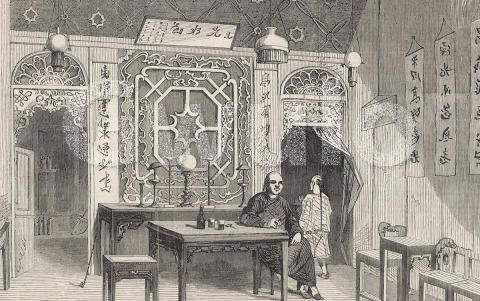

I send you also a sketch of the interior of a Chinese house. Everything in a native house is the perfection of neatness; everything is in its proper place, and beautifully clean. I do not know a nation equal to the Chinese for their tidiness. The ornaments of the room are quaint, but very pleasing. The native merchant is sitting down smoking his cigar. Directly we entered the house he sent us up beer, cigars, water, and biscuits; and soon after joined us. The walls are covered with writings and paintings. There is abundance of lamps as you see.

We have occasionally "a Liberty Day ashore,” when the tars drink and dance incessantly. Many of them had not been ashore for a year, so that their joy may be excused, for the grog-shops here are very numerous. The walls are generally decorated with pictures of European life. There are plenty of visitors of both sexes; and outside the door generally stand a crowd of gaping Chinamen. One day I went into a shop and sat down to make a sketch, but was so completely surrounded by Chinamen that it was a case of drawing under difficulties. They are so fond of anything in the shape of a picture that you run the risk of being suffocated if you attempt outdoor sketching.

INTERIOR OF A CHINESE HOUSE AT HONG-KONG

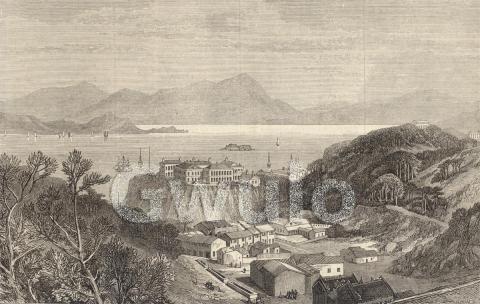

September 27, 1873 - The Illustrated London News

NEW ROYAL NAVAL HOSPITAL, HONG-KONG

The best early engravings are copied from good original sketches. But sometimes the engraver was given a rough sketch or even just a written description of a scene to work from, and allowed to conjure up the scene from his imagination. The accuracy of those engravings varied considerably, as you'd imagine.

In later years, the engraver was given a photograph of the scene instead of a sketch, and told to reproduce that. I suspect the next four engravings were copies of photos. They all appeared in "The Graphic", another weekly illustrated newspaper from Britain. It was first published in December 1869, and became a strong rival to the ILN.

June 2, 1888 - The Graphic

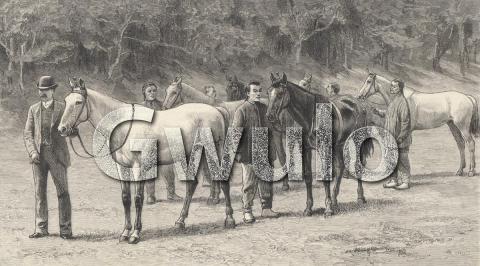

"LEAP YEAR," WINNER OF THE HONG KONG DERBY,

AND A STRING OF WINNERS FROM MR. JOHN PEEL'S STABLES

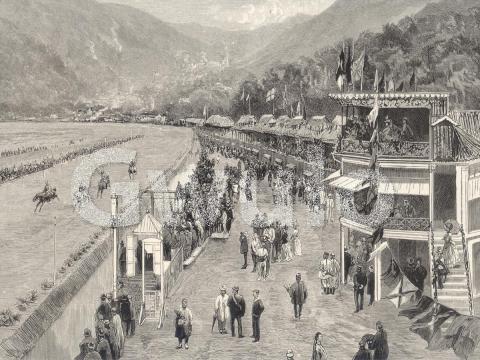

GENERAL VIEW OF THE COURSE IN THE HAPPY VALLEY

THE HONG KONG DERBY

NOTES AT THE ANNUAL RACE-MEETING OF THE HONG KONG JOCKEY CLUB

December 1, 1888 - The Graphic

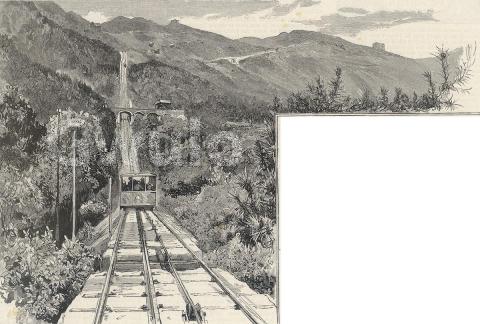

NEW HIGH LEVEL TRAMWAY AT HONG KONG

GENERAL VIEW OF THE LINE TAKEN FROM

A LITTLE BELOW THE BRIDGE OVER THE KENNEDY ROAD

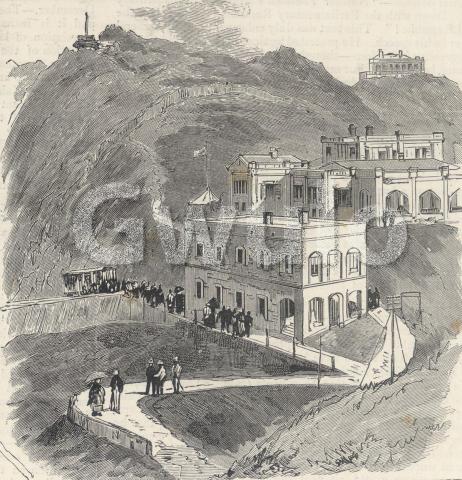

VICTORIA GAP, THE UPPER TERMINUS OF THE TRAMWAY,

SHOWING THE ENGINE-HOUSE

Back to the ILN for our last illustration.

July 18, 1896 - The Illustrated London News

JUBILEE STATUE OF THE QUEEN UNVEILED AT HONG-KONG

From a Photograph supplied by the Hon. J. H. Stewart Lockhart,

Hon. Secretary to the Hong-Kong Jubilee Committee.

STATUE OF THE QUEEN IN HONG-KONG.

Amid much brilliant ceremonial, and in the presence of some fifteen thousand spectators, the Jubilee statue of her Majesty the Queen was unveiled in Hong-Kong on May 28 by the Governor, Sir William Robinson. The erection of this fine memorial of the Jubilee year of her Majesty’s reign is not as belated as it sounds, the history of the statue being, briefly, as follows. When the Jubilee of her Majesty was being celebrated throughout the Empire, her loyal subjects in Hong-Kong were not behind their fellows in their desire to commemorate so historic an occasion. After some discussion the statue now erected was chosen as the most fitting memorial, and the necessary funds were speedily raised by public subscription. A commission for the work was given to Signor Raggi, the well-known sculptor of the Earl of Beaconsfield’s statue at Westminster. The work was first executed in marble, but more mature consideration decided that this material would be ill suited to the climate of Hong-Kong, and the statue was accordingly bought for the town of Sheffield, another, in bronze, being commissioned for Hong-Kong. When the second statue was completed it was exhibited in London, and eventually transferred to Hong-Kong.

But even after these initial delays its erection seemed doomed to be postponed, for no suitable public site was available, and the Jubilee Committee therefore decided to keep the memorial safely stored until the completion of the New Praya Reclamation. On this most commanding spot the pedestal has been some time in course of erection, the work being interrupted by the weather, but at last the statue has been established on its destined resting-place under a handsome domed pavilion of Portland stone designed to protect it from the weather’s ravages.

This last illustration shows an unusual combination of techniques. As the subtitle states, it was first supplied to the ILN as a photograph. Zooming in to the page, we can see that a painting was made of the photograph, and it is the painting they reproduced.

Zooming in still further shows that this image is an impostor, and doesn't belong in this collection of engravings at all.

The illustrations from 1888 and earlier were printed using wooden blocks that had the image engraved onto them - that's why we call them engravings. But the dots in this last picture from 1896 picture show it was printed using a metal plate that had a halftone representation of the painting. So a new photograph was taken of the painting, and the new negative was used to copy the image to a metal plate covered with a light-sensitive coating. The plate went through an etching process, which left the metal plate ready for printing. This modern "halftone" process uses dots of varying sizes to give different levels of dark and light. It took off in the 1890s, eventually replacing engravings altogether.

If you've seen the original sketches or photos that were the sources of any of these illustrations, please could you let us know in the comments below? It will be interesting to compare them with the versions in the newspapers.

|

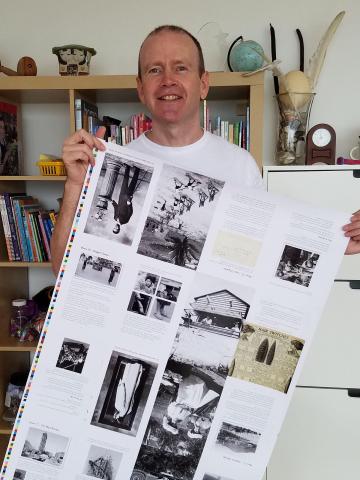

Gwulo book update: We've reached a major milestone - the printing is finished! Here's one of the printer's sheets I was given on Saturday. These show that the printing is complete, so now I just need the printer to do the binding, and then deliver the finished books to me in Hong Kong. On Saturday I'll post details of how to order copies of the new book.

New on Gwulo...

If you can leave a comment with any more information about these, it will be gratefully received.

Some of the new photos added:

Click to see all recently added photos. |

Comments

south vs north

it is interesting that they confused North / South

"On the south side of the island is the chief town, Victoria; and on the north side is the town of Stanley, named after the present Earl of Derby when he was Lord Stanley, and held the seals of the Colonial Office."

Illustrated London News pictures

Thank you for inserting them, David. Very interesting. I too noticed that they had switched North and South. Along with confusion over East and West this seems to happen quite frequently in all sorts of descriptions We should be wary of this simple but potentially misleading error.

Lord Stanley

The writer of the entry for Dec 27 1856 is correct when he states that Stanley was named after the Earl of Derby, but he would have been more accurate if he had given him his actual title at the time - Secretary of State for War and the Colonies.

This post was actually separated into 2 at about the time the article was printed, i.e. Secretary..for War and Secretary...for the Colonies.

'RP Leitch' was Richard

'RP Leitch' was Richard Principal Leitch 1827-1882 and he seems to have been quite prolific and well regarded. 'Del' means drew so he was the artist, though this snippet suggests he may have signed a China engraving based on someone else's original.

http://www.radnorshire-fine-arts.co.uk/brand/leitch-richard-principal-18...

North-south

It seems that many people mentally invert Hong Kong Island's north-south polarity. I am interested to hear of others who've had the same feeling - and their geographical background, which is my hunch as to what causes this phenomenon. Other explanations are possible.

Engravings

I missed that North-South switch.

Early maps of the city were often drawn with the harbour (north) at the bottom of the map, so I wonder if that contributed to the confusion? eg

Thanks to Nicola for identifying the artist too - great job on deciphering the signature. The British Museum says he worked for the Illustrated London News for thirty years, 1847-77, and was a draughtsman and wood-engraver as well as a painter: http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/ter...

Maps printed 'upside down'

Maps printed 'upside down' may have been a cause, and/or a result, of the confusion.

Perhaps British cartographers felt that it looked more proper to have the land north of the sea? Just a guess really.

My interest is to relate it to the same mental error made by friends and acquaintances today.

North South problem

Hi Martin

I agree that this is true even today and with people more commonly confusing East and West and, rather oddly, RIGHT and LEFT. One friend, when a passenger, often says , 'Turn right here,' while putting out her left hand. Perhaps the North / South orientation might be linked to early (and even modern) drawings/paintings of Victoria usually being done from the harbour, i.e. the North. People would be used to this aspect and would possibly more easily understand the map if it had the same orientation. Just a few thoughts! Andrew