Christmas Dinner in Hong Kong

Primary tabs

Traditionally, Christmas Dinner was the biggest meal of the British calendar. Here's a look at how the meal has been enjoyed in Hong Kong over the years, based on mentions and photos here on Gwulo.

Sweetmeats in the 1800s

The oldest one is an advert from Lane, Crawford, which appeared in the newspapers in January 1879. It lists a remarkably broad range of items on sale: woollen socks ... horse clippers ... salamanders for heating baths, ... crocodile scent cases ... and MANY more, but the middle part of the list must have been the leftover stock that should have graced a Christmas table:

"... plum puddings, Christmas cakes, mincemeat, Smyrna figs, Elva's plums, crystallised fruits, dragees, French and English bonbons, chocolate for dessert, assorted cosaques, telephone crackers, conference crackers, aquarium crackers, ..."

Those assorted crackers weren't for eating, but for pulling. They pull apart with a bang, to reveal a trinket, a joke to make you groan, and a paper hat that doesn't fit. Tom Smith was the man who invented the Christmas cracker, and his company supplied them to Lane, Crawford. His "telephone crackers" show how his marketing tracked the latest fashions - they were manufactured in 1878, the year that the first commercial telephone exchange opened.

We don't have any Christmas memories for the following 60 years, but it's a safe bet to assume the meals followed a similar pattern until...

The 1940s - Christmas in wartime

There was little to celebrate on Christmas Day, 1941, the day that Hong Kong surrendered to the Japanese. That year's Christmas Dinner was a varied experience for the authors of the wartime diaries:

- ((In the evening, we)) had Xmas pudding ((heated on a primus)) absolutely delicious, and chocolate and sweets; Barbara Anslow

- An order comes through from the Police Chief Pennefather-Evans to get rid of all liquor. Mr Brown the manager calls all the men in the Exchange Building and explains that there is a large stock of liquor, wines and spirits stored in the basement. He asks for volunteers, so we set to work opening hundreds of cases of whisky, gin, brandy, port, wines, champagne, etc. smash the neck of each bottle and pour the contents into buckets and carry them up to street level and pour it down the drains. Mr Brown tells everyone that if they want a bottle or two to drink take it now. Amongst the 15 males were quite a few noted boozers, but they were so shocked at the surrender I saw nor heard of one taking as much as a bottle. I think it was a reaction or kind of daze of not knowing what was going to happen tomorrow, and the fact of seeing so much good liquor go down the drain. Patrick Sheridan

- When the blanket on the side window was drawn back, Laura Lou found her gifts of a candy bar, a new dress for her doll, a glass of jam and an old lady’s purse. We all got food of some kind which made us all happy because we already seemed to realize the value of food. Laura B Ziegler

- We ate our Christmas lunch (bully beef and some oranges) walking about nervously, while distant bombs, shells and machine guns rattled on. About 4 p.m. the telephone rang, and hurriedly a discreet voice said, "It's all over; we've surrendered." Harry Ching

The next three Christmases were spent under Japanese rule. Food became scarcer and scarcer as the Allied blockade of Japan took effect, but the every effort was made to make the Christmas Dinner something special.

In Stanley Internment Camp, internees' lives revolved around food, so it's not surprising that Barbara Anslow's diary for Christmas day 1942 records the day's meals in detail. There's a cooked breakfast, cooked lunch (with a special treat - "NO RICE"), afternoon tea, and a supper to finish it off. This sudden intake of rich food wasn't all good news though, as Barbara notes, "'Xmas pudding' Mabel made was grand, we had it with custard power mixed with wong tong. I have a stomach ache and deserve it."

In 1943, it's R E Jones who records the day's meals at Stanley. By the late afternoon he's facing a rare probem, "Had to ease top button", but he ends the day on a high note, "To bed with full tummy for once."

By the end of 1944 the typical daily rations for Stanley Camp's internees were very meagre, making the Christmas meal a standout event. Barbara writes: "Japs had sent flat duck in rations - hospital kitchen put out a terrific meal of beans, pumpkin, 'ragout of duck', greens, and a pudding with wong tong syrup. Married Quarters had pasties and rissoles." R E Jones was a happy recipient of one of those pasties, "Excellent meal pm. Rice, baked sweet potato, stew & savoury pasty."

It's not clear whether our diarists would have lived to see another Christmas under Japanese rule, as starvation was beginning to be a real risk. The sudden end of the war in August 1945 was their saviour, and meant that by Christmas most of them had left Hong Kong and were back "home".

The wartime diaries naturally finish with the end of the war, but Barbara has written about what happened next, and remembers "We spent Christmas Day with the family at Gillingham, the table graced with a rare turkey". For most of Britain, still under rationing, the Christmas dinner table was a shadow of its pre-war self. But to the freed internees, it must have been a feast.

The 1950s - Christmas in the armed forces

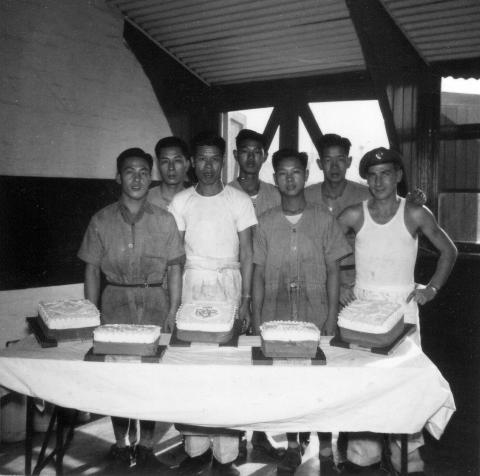

In the 1950s, Britain still had National Service, which meant that most of its young men spent 18-24 months in one of the armed forces. Fortunately for us, several of the men who spent their National Service in Hong Kong were keen photographers.

Andrew Suddaby, here with the RAF at that time, remembers that "Each Watch or large group of airmen held an annual Christmas dinner down at one of the restaurants in Central. It made a change from the, often not very good, food in the Airmen's Mess."

But on Christmas Day, it was back to the Mess for the official Christmas Dinner.

You'll notice how young the faces look - men started National Servicemen in their late teens or early twenties. It would be the first Christmas overseas for most, and I guess many were experiencing their first Christmas away from home. So it was a chance to enjoy some familiar traditions, and also a chance to get some good food. Unlike the 1940s internees, this group were never short of food - but as Andrew mentioned, the quality wasn't always the best!

Still, the Christmas meal was a step up from the usual, with better ingredients provided, and a chance for the cooks to show what they could do.

The three photos above were all taken at RAF Sek Kong, where the men were allowed to wear casual clothes. The men in uniform in that last photo are the officers and senior NCOs. It was the custom for them to serve the Christmas meal to airmen and corporals.

Andrew was at RAF Little Sai Wan where conditions were more formal, and all men were expected to wear their uniforms.

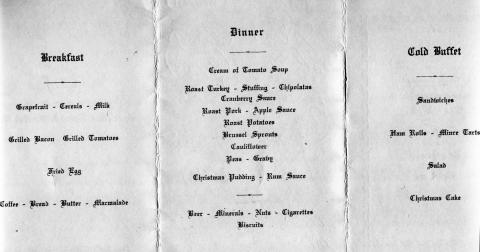

Here's a look at the food on offer:

Apart from the food, the "Dinner" section also includes: "Beer - Minerals - Nuts - Cigarettes - Biscuits". The beer bottles, likely San Miguel, are in evidence on the tables above, and also in this photo of soldiers at Sham Shui Po:

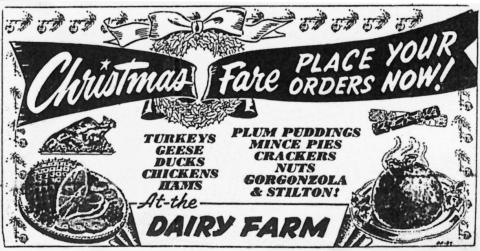

Outside the military camps, civilian Hong Kong's Christmas Dinner was back to pre-war standards. The items on sale at Dairy Farm in 1950 don't look very different from that 1870s advert we started with:

I hope you find some of your favourites on the menu this Christmas, finish with a full tummy like R E Jones, and avoid Barbara's indigestion!

Merry Christmas,

David

PS Thanks to everyone who shared their photos and memories of Christmas Dinner with us. If you can add any more, please upload a photo or leave a comment below.