The following is a chapter from A Small Band Of Men - An Englishman's Adventures in Hong Kong's Marine Police:

21. DEADLY GAME

亡 命 遊 戲

Since the days of the Opium Wars, Hong Kong has been on the trading route between East Asia and the rest of the world. Its geographically strategic location made Hong Kong a financial and economic gateway to China. It also made it the ideal platform for illegal trading and smuggling between the colony and China.

By the late 1970s, China had started to open its doors to foreign investment. By the mid-1980s and early 1990s, its economy was developing rapidly to the extent that there was a surge in the number of wealthy Chinese with money to flaunt. The desire for high-end luxury goods, from cars to clothes and jewelry, especially from Europe and America, continues used to grow. At the top of the must-have list of the new elite in China were cars and also electronics, such as VCRs and TVs. High taxes and duties in China meant these products were still in short supply.

At the conclusion of the Seagull case, I was assured by Jack Devereux that there would be no more redeployments of either Joe or myself.

“I want you to focus on getting to grips with this cross-border smuggling,” he said. “I have spoken with the Commissioner, and he agrees. This is now the priority.”

In the few months I had been away, the volume of goods crossing the border by illegal means had grown significantly. To meet an increased demand, the gangs had upped their game by manufacturing bigger, faster speedboats. Speedboats in which they could pack much more cargo, and stay ahead of the new high-speed pursuit vessels of the Marine Police. These bigger, faster smuggling speedboats soon picked up the nickname daai fei, literally ‘big flyer.’ They were sixty-foot, grey moulded fibreglass speedboats fitted with up to five powerful 250 or 300 horsepower engines, which gave them top speeds of up to eighty knots (ninety mph). The open cargo compartment of the daai fei was big enough to accommodate a luxury car or four hundred VCRs. Because the daai feis were purpose-built for illegal activity, they also came with defense and escape capabilities. In order to protect the crew from gunfire, the coxswain’s position was surrounded by metal plating, and the bow section was reinforced with an armored tip which could be used to ram anything or anyone that got in its way. In a press article at the time, Jack Devereux described the daai fei as ‘a death machine, a military tank with the acceleration of a Ferrari.’

By the end of 1990, smuggling by daai fei was a multi-million-dollar operation, and our job was to stop it using whatever means we could devise.

“You just watch yourself, Leslie Boy,” advised Don Bishop one afternoon at Marine HQ.

“Thanks Don,” I replied. “I assume you are referring to the nocturnal activities of my unit?”

“I am indeed, dear lad. I saw one of those daai feis the other day. Death traps. Those smugglers are ruthless. They’ll stop at nothing to avoid arrest. And I mean nothing.”

Don fixed me with one of his one-eyebrow-raised stares then turned and stomped off. It was good advice. Arrest avoidance tactics by these mainland-based gangs was something never too far from my thoughts.

Another feature of these syndicate’s activities was the luxury car ‘steal to order’ business. Anyone in China with the ready cash could place an order for a specific make, model, even color, of vehicle. The Hong Kong-based members of the syndicate would then simply go out into the streets and steal one. The operation was slick and professional. After stealing the ordered vehicle, it would be driven immediately to a prearranged loading point, a secluded jetty in the rural areas of the New Territories, where a mobile crane and crew were waiting with a specially-designed sling to winch the car into the waiting daai fei alongside a pier. The road-to-boat transfer took no more than sixty seconds to complete. The daai fei with the stolen car on board would then accelerate off into the night on its way to mainland China. The profit on this few hours work was, of course, one hundred percent of the selling price of the car in China. In 1990 alone, 660 luxury vehicles, mostly Mercedes Benz, were reported stolen and never recovered. We suspected that all 660 ended up in China.

It was almost all night-time operations for the unit. The syndicates that operated their fleets of daai feis preferred the cover of darkness, for obvious reasons. Our food, rest and sleep were taken during the day at our forward operating base in Tolo Channel. Our home lives, what there was, remained tense.

“Kitty is on my case again,” said Joe one morning after returning to the base. We had had a long, cold, fruitless night. Joe and I were in the locker room. He was peeling off layers of thermals. Joe had by now overcome his one-man crusade against certain mainland coxswains. He was seeing things clearly once more.

“She is still asking me how long I am going to continue with the unit. Her two main points are always the same. It’s the danger and the unsociable hours. She also says she has hardly seen me in the past six months and that when she does I am always too tired to talk. And, of course, I keep getting the ‘and every night I can’t sleep with worry in case you get hurt, or worse!’ lecture.”

Despite the unsociable hours and the occasional brush with danger, SBU had a very low turnover of staff. I actually cannot recall any officer ever asking for a transfer out. We were seen as an elite unit, and there was a long list of Marine officers wanting to join. We were, understandably, very selective on who we took. We frequently had to rely on each other in close-quarter situations so it was important to have the right man standing next to you.

Tolo Channel is a ten-mile long narrow body of water on the north-east tip of Hong Kong’s New Territories. It connects, at its most inner point, the towns of Sha Tin and Tai Po and, at its outermost point, the open sea and the Chinese coast beyond. The Chinese name for the mouth of Tolo Channel is appropriately Chek Mun, or Red Gate.

Tolo Channel was a smuggler’s dream. Not only did it connect two large towns with the open sea and the China coast, there were also twelve remote piers and jetties scattered along both sides of the channel, offering secluded loading points. All had good, quiet, roads leading to the urban areas. On a moonless night, the channel was dark, making it easy to go undetected. And being a channel, its waters were invariably calm. This was an ideal location for high-speed vessels to operate.

On the night of June 3, 1990, our unit was busy preparing their kit for the evening’s patrol. That day, we had been moored at the Marine Police base inside Tolo Channel. Our engineers had been fine-tuning our outboard engines, while our deck crews had been doing running repairs. By early evening, everyone was focused on that night’s task, checking and rechecking equipment — boat engines, weapons, communications – as well as coordinating map references and timings. Everything needed to be checked and double-checked.

Information had been received from our lookouts along the channel that there was quite a lot of motorized sampan movement around Sam Mun Jai Cove on the northern side of inner Tolo Channel. These sampans were the syndicate’s lookouts, their eyes and ears. It was the lookouts’ job to try and spot police movements and report in to their controller via either a shortwave radio or mobile phone. The controller would then decide on which loading points his daai feis would use that evening.

I found Joe Poon talking to a group of NCOs. We walked out of the briefing room and onto the pier. It was a moonless night. We stared out across the calm waters of the bay, into the darkness.

“Sir, there’s a message for you.” It was Joe’s radio operator, Billy Lee. He came running along the pier and handed me a scrawled handwritten note. “There’s information there could be a loading within the hour,” said Billy in his usual way before I could read it. He smiled and adjusted his glasses. I could see he was excited by the news. We had a chance of an arrest and the seizure of a daai fei.

“Thank you Billy,” I said.

Joe took a glance at his watch, “I suggest we move into Sam Mun Jai covertly, as soon as possible and see what's happening.”

I agreed. “Don’t forget, if we can get a clear view, and there is daai fei activity, we must wait for the loading to be complete before we move in. We need evidence of the act of smuggling in order to make the case stand up in court.”

“Let me lead,” Joe said, a firm tone in his voice. “I will use NVGs and wait until I have visual evidence then I’ll illuminate the bay with flares. We can move in, fast, and make arrests before the daai feis have time to shoot off.”

I turned to Billy. “Tell Mr Kwan to come and see me now, we need to get the unit ready.”

Billy was already on his way before I could finish my sentence.

Our aim, as always, was to get as close to the jetty as possible without being detected by any of the syndicate lookouts. We needed to wait until the daai feis had cast off from the jetty with a full load before we moved in to make arrests. If they were moving, they were then, in the eyes of the law as it stood at that time, in the act of exporting un-manifested cargo.

But with this strategy there came a high degree of physical risk. Once underway, a daai fei can reach high speeds in seconds. It then becomes a very dangerous game to try and stop it. With the days of putting a warning shot across the bows now a thing of the past, we were left with little in the way of safe methods of stopping these high-powered, armour-plated, craft. Some daai fei coxswains were not averse to ramming police vessels in order to avoid arrest.

Marine Police Headquarters, realizing the dangers involved in trying to combat this new method of smuggling by daai fei, made several representations to government for changes to the existing maritime legislation. Quite simply, we wanted the construction or use of vessels purpose-built for smuggling, to be made illegal. That way, we could seize these boats in circumstances that suited us, in the shipyards, and not at eighty knots during a high-speed chase in total darkness, as was currently the case. But the bureaucratic machine was slow.

That night, we knew the daai feis would make their way out of their home base on the Chinese side of Mirs Bay and down Tolo Channel shorty after dark. The syndicates wanted to utilize the whole night, or ten hours of darkness for each daai fei. Their first run therefore would be an early one.

At 1900, we set off for the outer waters of Sam Mun Jai Harbour. It was pitch-black except for the dull lights of my console. I watched Joe’s RHIB just ahead through my night vision goggles. It was usual for Joe to command the RHIBs that were going to attempt the arrest at the pier. His local knowledge of the bays and inlets and his ability to listen in to, and understand, the smuggler’s Chinese radio chatter, made him the best man for the job. It was invariably a situation where split-second decisions and good reflexes were of paramount importance. No one was better at this than Joe Poon.

As the unit’s senior officer, I placed myself in the role of pursuit commander. If one or more of the daai feis were to make a break for it, a decision would need to be made very quickly as what to do next. Many of the coxswains employed by the syndicates were mainlanders, some former military. These guys in particular didn’t want to be apprehended in Hong Kong waters, and would go to any lengths to avoid arrest.

I could see Joe just ahead. His RHIB was stationary so I maneuvered slowly alongside. We needed to maintain radio silence as we knew the syndicate lookouts had the means to monitor police radio channels. Joe was looking into Sam Mun Jai through his NVGs. We were careful to remain in the shadows, hugging the coast as we slowly approached the suspected loading area.

“What’s happening?” I asked.

Joe pulled his radio earpiece out and pointed into the darkness. “Two daai feis alongside the pier. A truck just pulled up and they are already transferring cargo into the boats. About ten to twelve men on the pier.”

I pulled my night vision goggles out of the cargo pocket of my trousers and took a look.

“They will be ready to go in under a minute,” I said.

“Yes,” replied Joe, “see you later, good luck.”

There was a sudden rev of engines and a pungent smell of petrol as Joe and his second RHIB took off for the pier.

I watched them move in. My sergeant, standing to my right, slung his Sterling submachine gun off his shoulder and checked the firing mechanism. He then flicked the action to automatic.

I watched as the men on the pier continued to carry boxes from the truck to the waiting daai fei. They worked quickly and efficiently, unaware that the fast police boats were approaching. Scanning back, I looked for Joe. The RHIBs were just few hundred feet from the pier and closing in. Then all hell broke loose. Joe had been spotted. Within a matter of seconds, the two daai feis were moving away from the pier, great plumes of grey smoke billowing from their massive engines as the coxswains hit the accelerator. On the pier, men ran in all directions leaving what was left of their cargo where it was. The delivery truck shuddered forward, its tailgate flapping at the rear, boxes tumbled out and crashed onto the road.

Joe’s two RHIBs circled off the pier, but it was too late for a safe interception. The two daai feis were already accelerating away: forty, fifty, now sixty knots. Joe and his second RHIB turned and attempted to get alongside, but the sheer speed of the bigger boats gave the policemen little chance.

I glanced left and right at the two RHIBs on either side of my own. With these two daai feis heading in our direction we were entering into the second phase of the game. I radioed for our coxswains to hold position. I’d worked with these men in situations like this dozens of times before. I trusted them completely. But what we didn’t need now was a sudden rush of blood to the head and someone trying to be a hero by blocking the channel with his RHIB. Now was the time to rely on this trust.

Joe put up a flare giving us a clearer idea of where everyone was and what was happening. Upon spotting our police vessels ahead, both daai feis swung away into Sha Tin Bay.

“What the hell?” I said to my sergeant. “Why have they gone in there? There’s no other way out, they have boxed themselves in?”

We watched as the two daai feis slowed down, their crews realizing their mistake.

“Mainland coxswains,” Joe’s voice came through my earpiece. “Looks like they left their local Hong Kong navigators on the jetty in the hurry to get away. They are disoriented, they are not sure of the way out of the channel.”

We now had five RHIBs in the mouth of Sha Tin Bay, and we all knew what would happen next. Before anyone could speak the two daai feis did a 180-degree turn and accelerated towards us. I slammed the throttles of my RHIB into reverse and began moving out of the way, I motioned for the others to do the same. Those daai fei coxswains were not going to stop for anything.

They came out of the bay doing eighty knots. The high-pitched scream from the banks of five 300-horsepower engines was deafening as they tore past. The bow waves caught our small fleet of RHIBs and for a few seconds we were thrown all over the place.

Joe shot up another flare and the channel lit up once more. We could see clearly both daai feis, which seemed to have parted company, but were both heading northwards towards the mouth of Tolo Channel and the open sea. While we had little chance of catching them now, we swung our RHIBs in their direction and followed. There was always the possibility that one would encounter a mechanical problem or, possibly, without a local navigator, run aground on the rocks while still inside Hong Kong territorial waters. Then we would have something.

I followed the daai fei that seemed to favor the middle of Tolo Channel. Joe, and one of the other RHIBs, went after the other. Possibly this coxswain believed that by running close to the coastline he had a better chance of finding the open sea and an escape route back to China.

“Sir!” screamed my NCO above the noise of our outboard engines. He was standing next to me and had been fiddling with his portable radio.

“Collision! There’s been a collision!”

He was pressing on his earphones, trying to make out what was going on. I quickly throttled down in order to reduce engine noise and we came to a complete stop. The NCO looked up.

“A daai fei has rammed one of our RHIBs!” he shouted.

I felt my guts sink. I immediately turned our boat around and headed back towards Three Fathoms Cove.

The unit was easy to locate as someone had illuminated the whole area with a flare. As we approached, I could see three of our RHIBs moored together in the bay. There was no sign of a daai fei so I eased back on the throttles and we slowed to a couple of knots. Some of our guys were sitting down in their boats, one of our NCOs appeared to be receiving treatment. He was sitting on the deck of his RHIB with his back to the console. Another officer sitting in one of the other boats was completely soaked and had obviously been overboard. I could see Kwan kneeling next to him. I had a really bad feeling now. I then spotted Joe sitting on the balustrade of the middle of the three RHIBs. His head was down, arms tightly wrapped around his middle. He was staring at the empty deck just in front. I moored alongside one of the outer RHIBs and climbed across the raft of boats to where Joe was sitting. I was about to speak when I noticed the uniform boots in the shadows of the bow section. I froze. As my eyes became accustomed to the change of light I found myself looking at the shape of a crumpled body.

“It's Billy,” said Joe without looking up. “It’s Billy Lee. He took the full force of the armor-plated bow of the daai fei.”

Marine Police Constable Billy Lee Kam-sing, age twenty-seven, lay dead on the deck in front of us. I felt the life drop out of me.

I can’t recall how long I stood there looking at the crushed body at the bow. “Billy Lee?” I heard myself say.

“He was hit by the armored bow of the daai fei, at eighty knots,” said Joe. “He’s a mess.”

I sat down next to Joe and looked out across the bay and the dark waters of the Tolo Channel.

Joe and Billy Lee’s RHIBs had been tracking the second daai fei along the south side of the channel. As they passed Three Fathoms Cove, the daai fei did a 180-degree about-turn and headed directly for the two smaller police boats. Although the coxswain of the Billy Lee’s RHIB made several attempts to avoid the daai fei as it careered towards them, it smashed at full-speed into the starboard side of the RHIB. The momentum of this very heavy speedboat lifted it over the forward section of the police pursuit craft, and it hit the water on the other side. As it flew across the top of the police RHIB, it hit Billy Lee face on. He was killed instantly.

The physical impact of the daai fei colliding with the RHIB also flung the two other police crew members overboard. Joe Poon pulled them both from the sea seconds later. These two now sat on the deck trying to come to terms with what had just happened. Kwan was looking after them.

“They are both in a state of shock,” he said. “Physically they seem okay, not seriously hurt.” Kwan stood up and stepped over to Billy’s body. He was silent for a while, “I’ll get something to cover him up,” he said finally.

I looked again at Lee’s smashed body. This was a deliberate attempt by those onboard the daai fei to ram and render the police vessel inoperative. It was an act of murder.

Joe was the first to pull himself together. “I am going up the channel, to see if I can find the bastard,” he said. “That daai fei may have experienced mechanical problems or even hit the rocks. If I find him. . .” Joe turned away.

As a sergeant covered Billy Lee’s body with a plastic sheet I asked for a radio. I had to begin the process of reporting the death of a young officer killed in the line of duty — all over a boatload of VCRs. I thought of Billy’s family, his parents. They would probably be at home, while I sat here in this boat with their son, crumpled on a metal deck under an oily tarpaulin, his life finished. I thought of my own wife at home, and the families of everyone in the unit. I had difficulty finding the words to make the report. It was going to be a tough in the weeks ahead.

Joe returned two hours later looking tired. “Nothing,” was all he said. He slumped down on the deck and put his head in his hands.

We all knew the risks of going up against the daai fei gangs, and we all suspected that one day it would result in something awful. But this was the first officer from the unit to be killed while on duty.

“Some of the younger ones,” said Joe Poon next morning, after he and few others had cleared away their gear, “are talking about taking the law into their own hands, by orchestrating some kind of revenge action. I suggest we send some of them home on leave. They are angry. They need time to cool down.”

There were lots of messages of condolences. Jack Devereux came out to speak with the unit. Surprisingly, so did Don Bishop, in order to express his sympathy, a show of solidarity. I appreciated these efforts.

There was an inquiry into Billy’s death. PHQ went through our operational tactics with a fine-toothed comb. Jack Devereux was summoned to see the commissioner, to explain. The old man went armed with a file full of letters requesting changes in maritime legislation. The ones he had been asking for, for over a year.

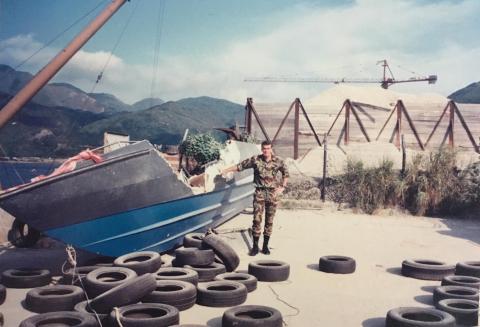

As a result of the enquiry into Billy Lee’s death, the law was changed. It became a crime to construct, own or operate a vessel that was deemed purpose-built for smuggling. Within a matter of days, all known areas where daai feis were manufactured, moored, stored or hidden were raided. Arrests were made and prison sentences doled out. Dozens of daai feis were seized and before long, all Marine Police bases around Hong Kong resembled scrap yards, cluttered with grey hulls and large outboard engines. The Marine North Division base, located inside Tolo Channel itself, had so many speedboats piled up in its compound, it became known by the press as the ‘Daai Fei Graveyard.’ Change had finally come - but it had come at a cost.

For details of the book and where to buy it, see: https://gwulo.com/node/47507