LIU KUNG TAO

Audrey and I were born on the island of Liu Kung Tao (Duke Liu's

Island) off the coast of Shantung in North China. Shantung means

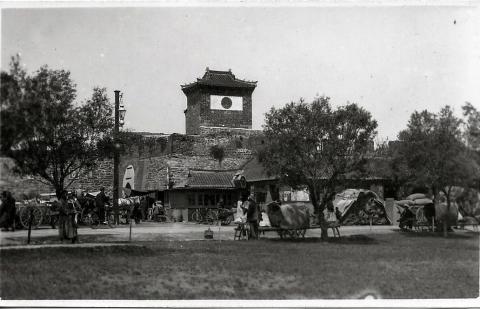

"East of the Mountains". The Island was part of the territory of

Wei Hai Wei which had been leased to Great Britain in 1898 to be a

summer base for the Royal Navy's China Fleet. The leased territory on

the Chinese mainland consisted of the 14th century walled city of

Wei Hai Wei, founded by Hung Wu, the first Emperor of the Ming

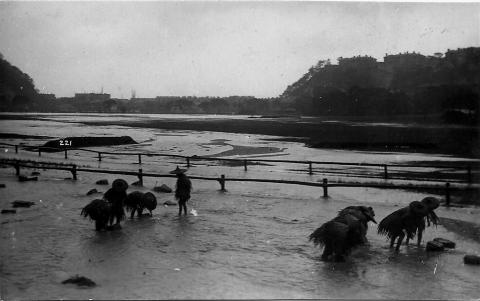

dynasty; and a strip of land about fifteen miles long, lying between a

chain of hills and the sea. There were many villages and temples, and

all the countryside was cultivated.

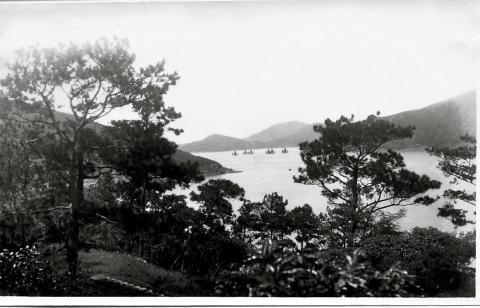

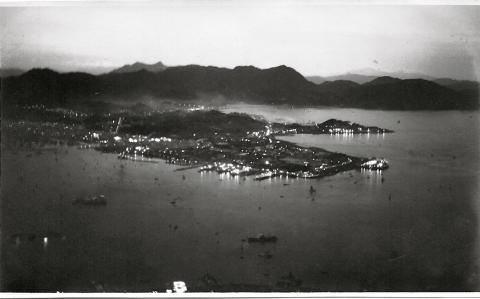

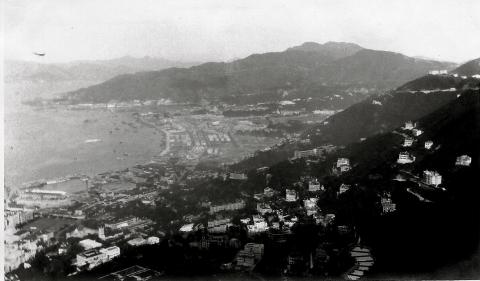

Our little Island, consisting of hills, and measuring only about

three miles by one and a half, lay about three miles off shore,

and because it partially blocked the entrance to the Yellow Sea, there

was a good sheltered harbour between it and the Mainland. Perhaps Duke Liu was the Governor of this north-eastern corner of the Shantung

peninsula, when the Emperor Hung Wu fortified it and named it

Wei Hai Wei (Majestic Sea Defence). At one end of the harbour was

tiny Sun Island, containing the remains of a Ming fort, and there were

old ruined forts on Liu Kung Tao and the Mainland as well.

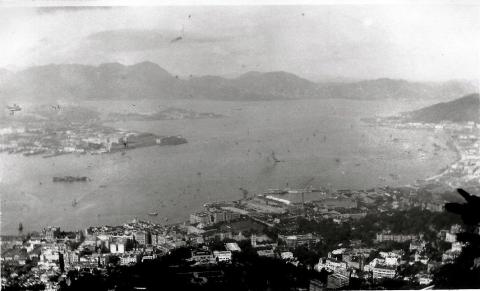

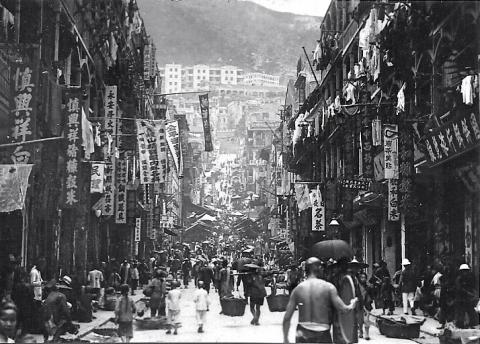

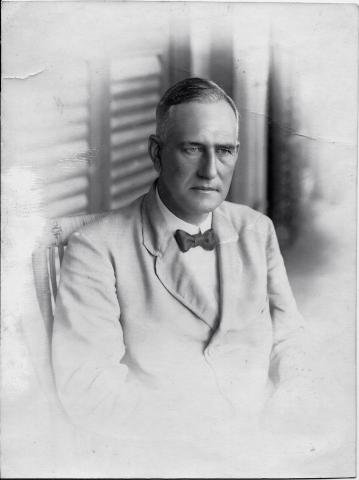

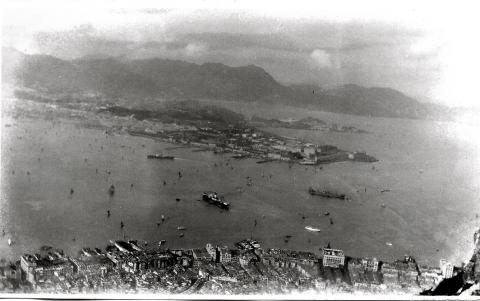

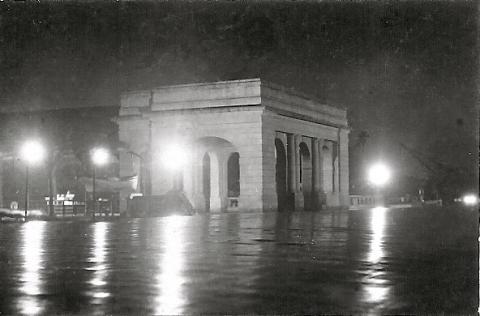

Our father and mother, Joseph William and Mabel Steel, arrived in

Wei Hai Wei from London in 1909 after a voyage of about six weeks

by a P. & 0. steamship (the Peninsula and Oriental Line) to Hong Kong; and from there by a coastal steamer, another five days.

The ships used to anchor in Wei Hai Wei harbour, and the passengers would go ashore in a steam launch.

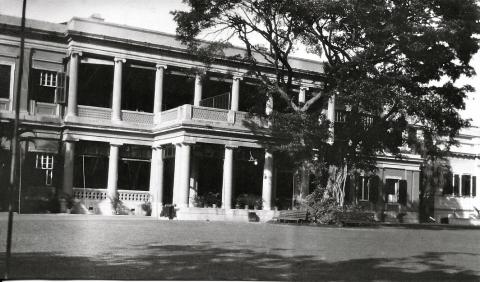

Liu Kung Tao, the Island, as it was always called, was the Royal

Navy's headquarters in Wei Hai Wei, and my father had been

appointed by the Admiralty to the Victualling Store Depot of the

Dockyard, the department responsible for supplying the ships of the

Royal Navy. The few British people on the Island were all connected with the Navy, and lived there all the year round, although the

China Fleet only spent the summer there. On the highest hill

was a flagstaff, symbol of a Naval establishment.

Our parents lived in Creek Cottage, half way up the hill. It was a

single-storeyed house of brick and stone, with a roof of green tiles,

Chinese in style. The garden was surrounded by a stone wall,

ornamented with bricks and green tiles on top. There were acacia

trees with sweet scented white flowers growing on the Island and in the gardens of the houses were sunflowers and hollyhocks and

cornflowers. I was born in this house on the 20th October 1910 at 6.30 a.m. It was a Thursday. "Thursday's child has far to go"

is a saying that was true for me. The only doctor in Wei Hai Wei,

Dr. Muatt, lived on the Mainland, so whether he arrived in time

for my birth I do not know, but Aunt Daisy Jennings acted as

midwife. In later years she gave me the gold chain bracelet, with my name and date of birth engraved on the heart, which

Dadda and Mamma had given her to celebrate my birth.

I was christened in the little Church by the Rev. Mr. Burnett,

a missionary, and named Betty Caroline Pringle, the last being my

mother's maiden name. My godmother was Mrs. Marsh. There is a

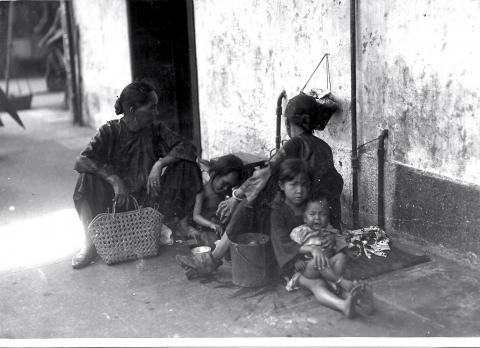

photograph of her daughters Maud and Edith, my Amah and me on my first birthday, with my huge teddy bear. The Marshes must have

left Wei Hai Wei when I was very young, for I have no memory of

them. My Amah's name has been forgotten, but she looks kind and is neatly dressed, as all Amahs were, in a white jacket and black trousers, with her smooth black hair drawn back from her face and worn in a bun at the back, the style so becoming to Chinese women.

And she wears bracelets and earrings, probably of jade or gold, as was customary. Our cook boy was Hing Yu, a tall handsome

Shantung man, who in later years joined the Hong Kong Police with

the Wei Hai Wei contingent, becoming a senior Police officer, and

returning to Wei Hai Wei from time to time to recruit new young men. There was a black and white spaniel, and a canary bird in a cage, popular in those days. In the bathroom was a "Soochow tub", a deep round earthenware bath, adorned with dragons. Everyone in Wei Hai

Wei used these bath tubs.

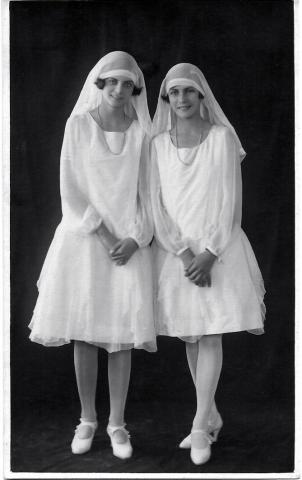

Audrey was born in Creek Cottage on the 20th April 1912. She was

christened Audrey Mabel Pringle. Her godmother was Aunt Daisy,

whose own child George Philip Charles Jennings was born on the

Island on the 23rd August 1913. His father Uncle George was a

Royal Marine who came to Wei Hai Wei to be the Clerk of Works

for a new barracks that was being built on the Island.

Mabel Forcey was also born on the Island in 1913. Her father

Frank Forcey was in the Wei Hai Wei Police, and was in charge

of the Prison on the Island. One wonders who the prisoners

could have been! We are told that they helped to build houses

and make roads on the Island.

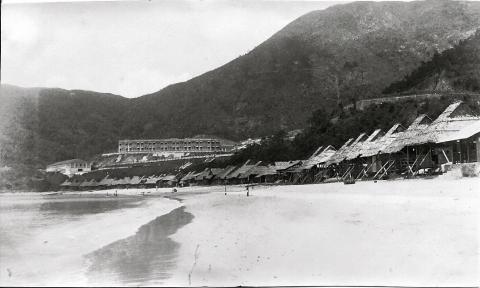

Our Amah used to take us for walks along the road that encircled

the Island. The hills were covered with pine trees, and when the

wind blew through the pines, they made a sighing sound, never

to be forgotten. The scent and the sound of pines will forever

recall those days of my early childhood.

The Masonic Lodge was close to our house. Dadda was a keen

Freemason, and there are photographs of him wearing Masonic

regalia. The Chinese called him "Four Eyes" because he wore

glasses. The Jennings lived at the foot of the hill, next door to

an Eastern Extension Telegraph Company family.

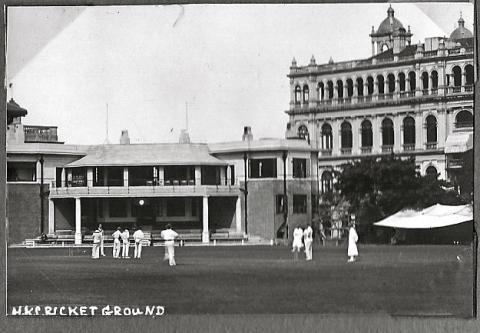

The Dockyard, Naval Stores and Canteen were on the sea front;

and a Naval jetty where in the summer Naval pinnaces brought men ashore from the ships. There are memories of sampans and fish

baskets and fishermen mending their nets. There was another jetty

for the steam launches "Foam" and "Alexandra" that carried

passengers between the Island and the Mainland. It was a

twenty minute crossing and very rough as the launch passed the

open sea at the harbour entrance. There is a memory of the relief felt by our nervous mothers when we arrived at the rather grandly named Port Edward on the Mainland.

In the summer there were tennis parties and teas, with cakes on

doyley-covered plates and pretty Japanese teasets; days on the

beach, walking with bare feet in the soft warm sand, building

sand castles, and paddling in the sea, our mothers with their long

skirts tucked up to their knees. They wore graceful long dresses

and the huge hats that perched on top of their piled-up hair had

to be kept in place with long hat pins. Summer in Wei Hai Wei

was delightful, sunny and dry and clear. On our birthdays there

were tea parties and birthday cakes, and ring games organised by

our mothers, "The Farmer's in the dell", and "Here we go

Looby-Loo", "Oranges and lemons", "Here we go round the

mulberry bush", "Gathering nuts in May"; Musical chairs and Huntthe Thimble.

In the winter we watched our parents skating on frozen ponds.

Audrey and I were dressed in lambswool coats and hoods, and Mamma wore a squirrel fur cape, and a muff to match to keep her hands warm. We wore boots with buttons like little balls all the way up the sides, that had to be fastened with a button hook.

Winter in Wei Hai Wei is intensely cold, with frost and snow,

and freezing winds blowing from Siberia.

At Christmas there was a children's party at the Masonic Hall,

decorated with streamers and garlands, and a huge candlelit

Christmas tree with presents for the children. But I was afraid of

bearded Father Christmas and ugly clowns.

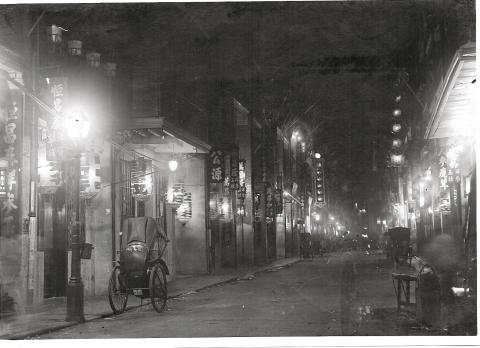

On the Island there were shops of many kinds: Ah Fong, the

photographer; Jelly Belly, the tailor; Shun Lee, another tailor;

Kataoka, the Japanese shoemaker; Yin Deh Tai, another

shoemaker; Ah Ying, the grocer. The Queen's Hotel, owned by

the Clarks and run by Mrs. Forcey, opened in the summer time and was used by Naval wives from Hong Kong and by visitors from

Shanghai. There were tennis courts and a golf course, a football ground for the sailors, a rifle range, a reservoir, (but we drank distilled water provided by the Dockyard) and a farm with

milking cows. And there were ancient wells dating no doubt

from Ming dynasty times.